He saw, and winced as he saw, that, while other European nations, even under despots, were comparatively active and energetic, his own people were sluggish and stagnant.

Continuing Russian Serfs Freed,

with a selection from The Development and Overthrow of the Russian Serf System in The Atlantic Monthly Magazine, Volume X by Andrew D. White published in 1862. This selection is presented in 8 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Russian Serfs Freed.

Time: 1861

Place: Russia

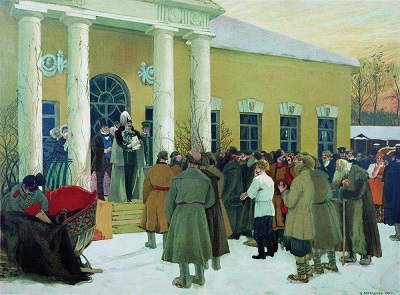

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Foremost of all the edifices on which Nicholas lavished the wealth of the empire stands the Isak Church in St. Petersburg. It is one of the largest and certainly the richest cathedral in Christendom. All is polished pink granite and marble and bronze. On all sides are double rows of Titanic columns, each a single block of polished granite with bronze capital. Colossal masses of bronze statuary are grouped over each front; high above the roof and surrounding the great drums of the domes are lines of giant columns in granite bearing giant statues in bronze; and crowning all rises the vast central dome, flanked by its four smaller domes, all heavily plated with gold.

The church within is one gorgeous mass of precious marbles and mosaics and silver and gold and jewels. On the tabernacle of the altar, in gold and malachite, on the screen of the altar, with its pilasters of lapis lazuli and its range of malachite columns fifty feet high, were lavished millions on millions. Bulging from the ceilings are massy bosses of Siberian porphyry and jasper. To decorate the walls with unfading pictures, Nicholas founded an establishment for mosaic work, where sixty pictures were commanded, each demanding, after all artistic labor, the mechanical labor of two men for four years.

Yet this vast work is not so striking a monument of Nicholas’s luxury as of his timidity. For this cathedral and some others almost as grand were, in part at least, results of the deep wish of Nicholas to wean his people from their semi-idolatrous love for dark, confined, filthy sanctuaries, like those of Moscow; but here again is a timid purpose and half result; Nicholas dared set no adequate enginery working at the popular religious training or moral training. There had been such an organization, the Russian Bible Society, favored by Alexander I; but Nicholas swept it away at one stroke of the pen. Evidently, he feared lest Scriptural denunciations of certain sins in ancient politics might be popularly interpreted against certain sins in modern politics. The corruption system in Russia is old, organized, and respectable. Stories told of Russian bribes and thefts exceed belief only until one has been on the ground.

Nicholas began well. He made an imperial progress to Odessa, was welcomed in the morning by the governor in full pomp and robes and flow of smooth words; and at noon the same governor was working in the streets with ball and chain as a convict. But against such a chronic moral evil no government is so weak as your so-called “strong” government. Nicholas set out one day for the Kronstadt arsenals to look into the accounts there; but before he reached them, stores, storehouses, and account-books were in ashes. So at last Nicholas folded his arms and wrestled no more. For, apart from the trouble, there came ever in his dealings with thieves that old timid thought of his, that, if he examined too closely their chief tenure, they might examine too closely his despot tenure.

We have shown this vague fear in Nicholas’s mind thus at length and in different workings, because thereby alone can be grasped the master-key to his dealings with the serf system. Toward his toiling millions Nicholas always showed sympathy. Let news of a single wrong to a serf get through the hedges about the Russian majesty, and woe to the guilty master! Many of these wrongs came to Nicholas’s notice; and he came to hate the system, and tried to undermine it. Opposition met him, of course; not so much the ponderous laziness of Peter’s time as an opposition, polite and elastic, which never ranted and never stood up — for then Nicholas would have throttled it and stamped upon it. But it did its best to entangle his reason and thwart his action. He was told that the serfs were well-fed, well-housed, well-clothed, well-provided with religion; were contented, and had no wish to leave their owners.

Now Nicholas was not strong at spinning sham reasons nor subtle at weaving false conscience; but, to his mind, the very fact that the system had so degraded a man that he could laugh and dance and sing, while other men took his wages, his wife, and homestead, was the crowning argument against the system. Then the political economists beset him, proving that without forced labor Russia must sink into sloth and poverty.

Yet all this could not shut out from Nicholas’s sight the great black fact in the case. He saw, and winced as he saw, that, while other European nations, even under despots, were comparatively active and energetic, his own people were sluggish and stagnant; that, although great thoughts and great acts were towering in the West, there were in Russia, after all his galvanizing, no great authors, or scholars, or builders, or inventors, but only two main products of Russian civilization, dissolute lords and abject serfs.

Nearly twenty years went by in this timid dropping of grains of salt into a putrid sea. But at last, in 1842, Nicholas issued his ukase creating the class of “contracting peasants.” Masters and serfs were empowered to enter into contracts, the serf receiving freedom, the master receiving payment in instalments. It was a moderate innovation, very moderate — nothing more than the first failure of the First Alexander. Yet even here that old timidity of Nicholas nearly spoiled what little good was hidden in the ukase. Notice after notice was given to the serf-owners that they were not to be molested, that no emancipation was contemplated, and that the ukase contained “nothing new.” The result was as feeble as the policy. A few serfs were emancipated, and Nicholas halted. The revolutions of 1848 increased his fear of innovation; and finally the war in the Crimea took from him the power of innovation.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Andrew D. White begins here. Nikolai Turgenieff begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.