He thought that the crisis of the Constitution had come, and therefore assumed a standpoint from which he could not be forced back to the worthless position adopted by Madison.

Continuing Jefferson’s Party Defeats the Federalists,

with a selection from Constitutional and Political History of the United States by Hermann Von Holst published in 1891. This selection is presented in 6.5 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Jefferson’s Party Defeats the Federalists.

Time: 1799

Place: Washington, D.C.

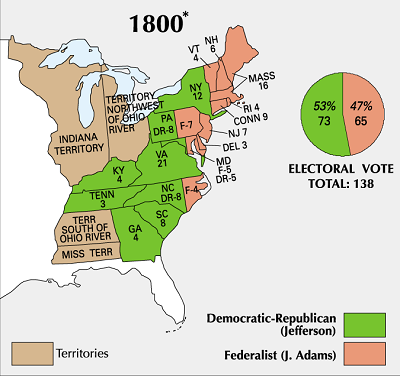

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In later times the admirers of Madison and Jefferson who were true to the Union have endeavored to confine the meaning of these resolutions within so narrow limits that every rational interpretation of their contents has been represented by them as arbitrary and slanderous. When about the end of the third and the beginning of the fourth decade of this century, the opposition to the Federal Government in Georgia, and especially in South Carolina, began to assume an alarming form, the aged Madison expressly protested that Virginia did not wish to ascribe to a single State the Constitutional right to hinder by force the execution of a law of the United States. “The resolution,” he wrote, March 27, 1831, “was expressly declaratory, and, proceeding from the Legislature only, which was not even a party to the Constitution, could be declaratory of opinion only.” In one sense, this cannot be questioned. In the report of the committee of the Virginia Legislature on the answers of the other States to the resolutions of 1798 we read as follows: “The declarations are expressions of opinion unaccompanied by any other effort than what they may produce on opinion, by exciting reflection.” But to concede that this was the sole intention of the resolutions of December 24th, is to deprive the words, according to which the States had the right and were in duty bound to “interpose” in case the General Government had in their opinion permitted itself to assume ungranted power, of all meaning.

But it has never yet been denied that these few words express the pith of all the resolutions. More was claimed than the right to express opinions —- a right which had never been questioned. If expression was not clearly and distinctly given to what was claimed, it was to leave all possible ways open to the other States to come to an agreement in all essential matters.

Jefferson was in this instance less cautious than Madison, and his vision was more acute. He thought that the crisis of the Constitution had come, and therefore assumed a standpoint from which he could not be forced back to the worthless position adopted by Madison in his celebrated report of 1800. Jefferson allowed it to depend on the further course of events whether force should be used, or whether only the right to employ force should be expressly and formally claimed. At first he was anxious that a middle position should be assumed, but a middle position which afforded a secure foothold. The Legislature of Kentucky had done this, inasmuch as it had adopted that passage in his draft in which it was claimed that the General Government and the States were equal parties, and in which it was recognized that the latter had “an equal right to judge” when there was a violation of the Constitution, as well as to determine the ways and means of redress.

Madison, and, later, Benton, as well as all the other admirers of the “Sage of Monticello,” who were opposed to the later school of secessionists, have laid great weight on the fact that the word nullification, or anything of a like import, is to be found only in the Kentucky resolutions of 1799, which did not originate with Jefferson. This technical plea in Jef1’erson’s behalf has been answered by the publication of his works. Among his papers two copies of the original draft of the Kentucky resolutions of 1798 have been discovered in his own handwriting. In them we find the following: “Resolved, That when the General Government assumes powers which have not been delegated, a nullification of the act is the rightful remedy: that every State has a natural right, in cases not within the compact (casus non federis), to nullify of their own authority all assumptions of power by others within their limits.”

That Jefferson was not only an advocate, but the father, of the doctrine of nullification is thus well established. It may be that Nicholas secured his assent to the striking out of these sentences, but no fact has as yet been discovered in support of this assumption. Still less is there any positive ground for the allegation that Jefferson had begun to doubt the position he had assumed. Various passages in his later letters point decidedly to the very opposite conclusion.

The Virginia and Kentucky resolutions produced no further immediate consequences. The recognized leaders of the Anti Federalists or Republicans had given their interpretation of the Constitution, and of the Union created by it. Their declarations remained a long time unused, but also unrecalled and unforgetten. The internal contests continued and their character remained the same. The revolution in the situation of parties now necessitated a change of front on both sides, and for a time also the battles between them were waged over other points and in part in another way.

The next collision was an actual struggle for supremacy. An inadequate provision of the Constitution alone made this battle a possibility to the Federalists; but the struggle over the question of the Constitution was after all considered only as a mere accidental collateral circumstance.

The Republicans (Democrats) had won the Presidential election by a majority of eight of nine electoral votes. Their two candidates, Jefferson and Aaron Burr, had each received seventy-three votes. They intended that Jefferson should be President and Burr Vice-President. Spite of this, however, they gave both the same number of votes, either not to endanger Burr’s election or because he became a candidate only on that condition. This was, considering Burr’s reputation and the boldness of his character, a dangerous experiment. Judge Woodworth charged that Burr had won over one of the electors of New York to withhold his vote from Jefferson, and that this was prevented only by the fact that the other electors of the State had discovered it in time. If this charge be well founded, it was by mere accident that the country escaped electing a man President whose name had never yet been connected with the Presidency by any party.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Hermann Von Holst begins here. Thomas Jefferson begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.