No one denied that the majority of the people, as well as the Republican electors, desired to make Jefferson President. After some hesitation his opponents resolved to try to elect Burr.

Continuing Jefferson’s Party Defeats the Federalists,

with a selection from Constitutional and Political History of the United States by Hermann Von Holst published in 1891. This selection is presented in 6.5 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Jefferson’s Party Defeats the Federalists.

Time: 1800

Place: Washington, D.C.

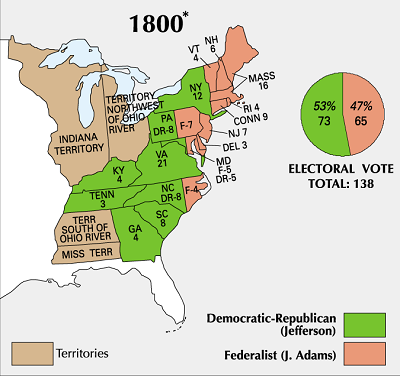

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

If an equal number of electoral votes should be cast for two or more candidates, the House of Representatives would have to elect one of them to the Presidency. In this case, the votes would be cast by States, and it would be necessary that a majority of all the States should vote for one of the candidates in order to have a valid election. The Federalists had a majority in the House of Representatives, but voting by States they could control only one-half the votes. This was just sufficient to prevent an election.

No one denied that the majority of the people, as well as the Republican electors, desired to make Jefferson President. But party passion had reached such a feverish height that the Federalists resolved, spite of this, to plant themselves on the letter of the Constitution, and to hinder Jefferson’s election. The possibility of electing their own candidates * was completely excluded by the Constitution. They could therefore do nothing except to obtain for Burr a majority of the votes of the States, or prevent an election. In case no President was elected by the States, they thought of casting the election on the Senate. The Senate was to elect a provisional President -— from among the Senators or not -—- who then might be declared President of the United States. Such a proceeding could not be justified by any provision of the Constitution; the case had not been provided for at all. It is impossible to say whether this is the reason why the plan was soon dropped; certain it is, however, that Gibbs’s statement, that such a plan never existed, is incorrect.

[Adams and Pinckney.—ED.]

After some hesitation they resolved to try to elect Burr. Only six States, it is true, voted for him, but it was necessary to win over only four votes in order to guarantee him the legal majority of nine States. The prospect of the success of both plans was at least great enough to inspire the Republicans with serious fear. Jefferson had written on December 15th to Burr that “decency” compelled him to remain “completely passive” during the campaign. But now’ he considered the situation so serious that he thought himself no longer bound by “decency.” He personally requested Adams to interfere by his veto, if the Federalists should attempt to turn over the Government, during an interregnum, to a President pro-tem. Although he declared that such a measure would probably excite forcible resistance, Adams refused to be guided by his advice.

Madison proposed another means of escape. He thought that an interregnum until the meeting of Congress in December, 1801, would be too dangerous; Jefferson and Burr should therefore call Congress together by a common proclamation or recommendation. This step could no more be justified by any provision of the Constitution than an interregnum under a provisional President. Madison himself conceded that it would not be “strictly regular.” But the literal interpretation was presumably the alpha and omega of the political creed of the Republicans. In spite of this the notion met with Jefferson’s approbation.

Between the two parties, or rather above them, stood the founder of the Federalist party himself. Even Hamilton advised that a concession should be made to the interests of political expediency. The possibilities which the equal electoral vote placed in the hands of the Federalists in the House of Representatives were to be used wherever possible, to force certain promises from Jefferson. But Hamilton did not wish to go any further. He declared the project of the interregnum to be “dangerous and unbecoming,” and thought that it could not possibly succeed. Jefferson or Burr was the only question. When his party associates also seemed to have adopted this view, he used his whole influence to dissuade them from smuggling Burr into the White House. He had written to Wolcott on December 16th, that he expected that at least New England would not so far lose her senses as to fall into this snare. When he was mistaken in these expectations he wrote letter after letter to the most prominent Federalists who might exert an influence directly or indirectly on the election. “If there be a man in the world,” he wrote to Morris, “I ought to hate, it is Jefferson.” Spite of this, however, he pleaded for Jefferson’s election harder than any Republican: “for in a case like this,” he added, “it would be base to listen to personal considerations.” Besides, he always dwelt with emphasis on the folly, the baseness, the corruption and impolicy of the Burr intrigue. In all these letters, some of which are very lengthy, he shows himself the far-seeing statesman, and examines everything with calmness and incision; but at times he rises to a solemn pathos. With the greatest firmness, but at the same time with a certain amount of regret, he writes to Bayard: “If the party shall, by supporting Mr. Burr as President, adopt him for their official chief, I shall be obliged to consider myself as an isolated man. It will be impossible for me to reconcile with my motives of honor or policy the continuing to be of a party which, according to my apprehension, will have degraded itself and the country.”

Hamilton’s intellectual superiority was still recognized by the Federalists, but spite of this he stood almost isolated from everyone. The repulsive virulence with which the party war had been waged during all these years, and the consciousness that their defeat was in a great measure due to the bitter and exasperating contentions among themselves, had dulled the political judgment and political morals of most of the other leaders. Hamilton’s admonitions were not without effect, but he was not able to bring about a complete surrender of the plan which was as impolitic as it was corrupt. The electoral contest in the House of Representatives continued from February 11th to the 17th. Not until the thirty-sixth ballot did so many of the Federalists use blank ballots that Jefferson received the votes of ten States and was declared the legally elected President. According to the testimony of the Federalist Representatives themselves, the field would not even yet have been cleared were it not that Burr had surrendered his ambiguous position. He could not completely and formally renounce his Republican friends, and hence the Federalists received from him only vague and meaningless assurances. All the dangers to the party and the country which would have been the con sequence of the success of their intrigues, they would have knowingly entailed in order to place at the head of the Government one whom they believed would turn his back on them the moment they had helped him into power. They would have been throwing dice to determine the future of the Union simply for the satisfaction of venting their hatred on Jefferson.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Hermann Von Holst begins here. Thomas Jefferson begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.