This series has eight easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: John Adams President.

Introduction

Among the political parties which have appeared in the United States since the founding of the Republic many arose through temporary influences and, with or without accomplishing noteworthy aims, came to an end. Of those which, whatever changes at one time or another they may have undergone, have long remained as persistent factors in American politics, that which almost from its origin has been known as the Democratic party is the oldest and at many periods has been the dominant party of the country. It has controlled the national or the executive Government under Presidents from Jefferson to Obama.

Under Washington and John Adams the national executive was controlled by the Federalists, a party formed in 1787 to support the Federal Constitution. Its importance ceased soon after the War of 1812. It was opposed by the Anti-Federal party, which stood against strengthening the National Government at the expense of the States. The name Anti-Federal went out of use about 1794, and the opponents of the Federal party took the name of Republicans. Their party was afterward called the Democratic-Republican, and still later (1828) the Democratic party, a name chosen as being “novel, distinct, and popular.” Of this party — as the Democratic-Republican — Jefferson is regarded as the founder, and the Democratic party to the present day is often called the “party of Jefferson,” while the term ” Jeffersonian Democracy ” is as frequently applied to its principles.

In an era where Democrats’ traditional Jefferson-Jackson Day celebrations are being renamed under the burdens of political correctness, this account may seem obsolete. It hearkens back to the day when history was encumbered by less political baggage than now.

The selections are from:

- Constitutional and Political History of the United States by Hermann Von Holst published in 1891.

- Inauguration Speech by Thomas Jefferson published in 1801.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

There’s 6.5 installments by Hermann Von Holst and 1.5 installments by Thomas Jefferson.

In the survey of Von Holst, an eminent authority on the political foundation and development of the United States, the origin and principles of the Democratic party are clearly set forth, and in Jefferson’s first inaugural, which follows, the political faith of the party, as given by himself, is definitely stated.

Thomas Jefferson was the founder of the Democratic Party.

We begin with Hermann Von Holst.

Time: 1796

Place: Washington, D.C.

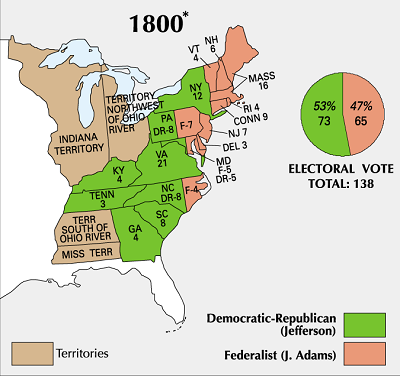

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Washington’s presence made Adams’s inauguration a moving spectacle. Adams remarked that it was difficult to say why tears flowed so abundantly. An ill-defined feeling filled all minds that severer storms would have to be met now that the one man was no longer at the head of the state, who, spite of all oppositions, was known to hold a place in the hearts of the entire people. The Federalists of the Hamilton faction gave very decided expressions to these fears, and Adams himself was fully conscious that his lot had fallen on evil days. It was natural that the com plications with France should for the moment inspire the greatest concern. The suspicion that France was the quarter from which the new administration was threatened with greatest danger was soon verified by events.

The inaugural address touched on the relations between France and the United States only lightly. Adams had contented himself with speaking of his high esteem for the French people, and with wishing that the friendship of the two nations might continue. The message of May 16, 1797, on the other hand, addressed to an extraordinary session of Congress, treated this question exclusively. The President informed Congress that the Directory had not only refused to receive Pinckney, but had even ordered him to leave France, and that diplomatic relations between the two powers had entirely ceased. In strong but temperate language he counselled them to unanimity, and recommended that “effectual measures of defense” should be adopted without delay. It is necessary “to convince France and the world that we are not a degraded people, humiliated under a colonial spirit of fear and sense of inferiority, fitted to be miserable instruments of foreign influence, and regardless of national honor, character, and interest.” At the same time, however, he promised to make another effort at negotiation.

Pinckney, Marshall, and Gerry were chosen to make an effort to bring about the resumption of diplomatic relations and the friendly settlement of the pending difficulties. Their efforts were completely fruitless. The Directory did not indeed treat them with open discourtesy, but met them in such a manner that only new and greater insults were added to the older. Gerry, for whom Adams entertained a feeling of personal friendship, was most acceptable to the Directory, because he was an Anti-Federalist. Talleyrand endeavored to persuade him to act alone. There can be no doubt whatever that Gerry had no authority to do so. Partly from vanity, and partly from fear of the consequences of a complete breach, he went just far enough into the adroitly laid snares of Talleyrand to greatly compromise himself, his fellow-ambassadors, and the Administration. The want of tact was so much the greater, as Talleyrand, by three different mediators, gave the ambassador to understand that the payment of a large sum of money was a condition precedent of a settlement.

In the early part of April, 1798, the President laid before the House of Representatives all the documents bearing on this procedure. If, even before his administration had begun, the general feeling of the country had been constantly turning against France, now a real tornado of ill-will broke forth.

The Anti-Federalists would willingly have given currency to the view that the ambassadors had been deceived by common cheats. But their ranks grew so thin that they were obliged to proceed with great caution.

While Jefferson had called the President’s message of March 19th mad, he now declared: “It is still our duty to endeavor to avoid war; but if it shall actually take place, no matter by whom brought on, we must defend ourselves. If our house be on fire, without inquiring if it was fired from within or from without, we must try to extinguish it. In that, I have no doubt, we shall act as one man.” That such would have been the case will be scarcely questioned now. But although the Anti-Federalists did not think of playing the part of traitors, and although they gave expression to their sympathy for France only in a suppressed tone, Jefferson was right when he said that “party passions were indeed big.” The visionaries became sober, and those who had been sober intoxicated. Hence the discord grew worse than ever.

A small number of the Federalists were anxious for war, and the rest of them considered it at least as probable as the preservation of peace. Warlike preparations were therefore pushed forward with energy. But it was not considered sufficient to get ready to receive the foreign enemy; it was necessary to fetter the enemy at home. The angry aliens were to be gotten rid of while it was not yet too late, and the extreme Anti-Federalists were to be deterred from throwing too great obstacles, at this serious time, in the way of the Administration. In the desire to effect both of these things, the so-called Alien and Sedition laws, which sealed the fate of the Federalist party and gave rise to the doctrine of nullification, had their origin.

The plan of this work does not permit us to dwell on the contents of these laws. Suffice it to say that for a long time they have been considered in the United States as unquestionably unconstitutional. At the time, however, there was no doubt among all the most prominent Federalists of their constitutionality. Hamilton even questioned it as little as he did their expediency. But he did not conceal it from himself that their adoption was the establishment of a dangerous precedent. Lloyd of Maryland had on June 26th introduced a bill more accurately to define the crime of treason and to punish the crime of sedition, which bill was intended for the suppression of all exhibitions of friend ship for France, and for the better protection of the Government. Hamilton wrote to Wolcott in relation to this bill that it endangered the internal peace of the country, and would “give to faction body and solidity.”

| Master List | Next—> |

Thomas Jefferson begins here.

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.