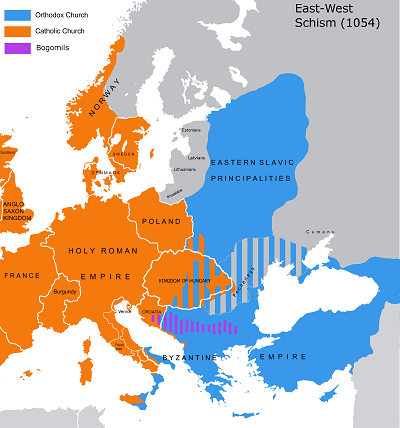

This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: East-West Problems Includes Religeon.

Introduction

In the division of the Greek Catholic Church from that at Rome, Protestant writers see a very natural and legitimate separation of two equal powers. Roman Catholics, regarding the Papal supremacy as established from the beginning, treat the division as a plot by evil and malignant men. Both viewpoints are here given but first a little background.

The Eastern, or Greek Christian, Church, now known as the Holy Orthodox, Catholic, Apostolic, Oriental Church, first assumed individuality at Ephesus, and in the catechetical school of Alexandria, which flourished after A.D. 180. It early came into conflict with the Western or Roman Church: “the Eastern Church enacting creeds, and the Western Church discipline.”

In the third century, Dionysius, Bishop of Rome, accused the Patriarch of Alexandria of error in points of faith, but the Patriarch vindicated his orthodoxy. Eastern monachism arose about 300; the Church of Armenia was founded about the same year; and the Church of Georgia or Iberia in 340.

Constantine the Great caused Christianity to be recognized throughout the Roman Empire, and in 325 convened the first ecumenical or general Council at Nicea, when Arius, excommunicated for heresy by a provincial synod at Alexandria in 321, defended his views, but was condemned. Arianism long maintained a theological and political importance in the East and among the Goths and other nations converted by Arian missionaries. In A.D. 330, Constantine removed the capital of the Roman Empire to Constantinople, and thence dates the definite establishment of the Greek Church and the serious rivalry with the Roman Church over claims of preeminence, differences of doctrine and ritual, charges of heresy and inter-excommunications, which ended in the final separation of the churches in 1054.

In A.D. 461, the churches of Egypt, Syria, and Armenia separated from the Church of Constantinople, over the Monophysite controversy on the single divine or single compound nature of the Son; in 634 the struggle with Islam began; in 676 the Maronites of Lebanon formed a strong sect, which, in 1182, joined the Roman Church. In 988, Vladimir the Great of Russia founded the Graeco-Russian Church, in which the Greek Church found a refuge, when Islam was established at Constantinople, after its capture by the Turks in 1453.

The selections are from:

- The Church and the Eastern Empire by Henry F. Tozer published in 1888.

- A Full Catechism Of The Catholic Religion, Preceded By A Short History Of Religion From The Creation Of The World by Joseph Deharbe published in 1863.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. There’s 4 installments by Henry F. Tozer and 1 installment by Joseph Deharbe.

Henry F. Tozer was an English writer who travelled to and wrote about Greece and Turkey and their histories. Joseph Deharbe was a Jesuit. His installment comes from his comprehensive work.

We begin with Tozer.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The separation of the Eastern and Western churches, which finally took place in the year 1054, was due to the operation of influences which had been at work for several centuries before. From very early times a tendency to divergence existed, arising from the tone of thought of the dominant races in the two, the more speculative Greeks being chiefly occupied with purely theological questions, while the more practical Roman mind devoted itself rather to subjects connected with the nature and destiny of man. In differences such as these there was nothing irreconcilable: the members of both communions professed the same forms of belief, rested their faith on the same divine persons, were guided by the same standard of morals, and were animated by the same hopes and fears; and they were bound by the first principles of their religion to maintain unity with one another. But in societies, as in individuals, inherent diversity of character is liable to be intensified by time, and thus counteracts the natural bonds of sympathy, and prevents the two sides from seeing one another’s point of view. In this way it cooperates with and aggravates the force of other causes of disunion, which adverse circumstances may generate. Such causes there were in the present instance, political, ecclesiastical, and theological; and the nature of these it may be well for us to consider, before proceeding to narrate the history of the disruption.

The office of bishop of Rome assumed to some extent a political character as early as the time of the first Christian emperors. By them this prelate was constituted a sort of secretary of state for Christian affairs, and was employed as a central authority for communicating with the bishops in the provinces; so that after a while he acted as minister of religion and public instruction. As the civil and military power of the Western Empire declined, the extent of this authority increased; and by the time when Italy was annexed to the Empire of the East, in the reign of Justinian, the popes had become the political chiefs of Roman society. Nominally, indeed, they were subject to the exarch of Ravenna, as vicegerent of the Emperor at Constantinople, but in reality the inhabitants of Western Europe were more disposed to look to the spiritual potentate in the Imperial city as representing the traditions of ancient Rome.

The political rivalry that was thus engendered was sharpened by the traditional jealousy of Rome and Constantinople, which had existed ever since the new capital had been erected on the shores of the Bosporus. Then followed struggles for administrative superiority between the popes and the exarchs, culminating in the shameful maltreatment and banishment of Martin I by the emperor Constans — an event which the See of Rome could never forget.

The attempt to enforce iconoclasm in Central Italy was influential in causing the loss of that province to the Empire; and even after the Byzantine rule had ceased there, the controversy about images tended to keep alive the antagonism, because, although that question was once and again settled in favor of the maintenance of images, yet many of the emperors, in whose persons the power of the East was embodied, were foremost in advocating their destruction. Indeed, from first to last, owing to the close connection of church and state in the Byzantine empire, the unpopularity of the latter in Western Europe was shared by the former. To this must be added the contempt for one another’s character which had arisen among the adherents of the two churches, for the Easterns had learned to regard the people of the West as ignorant and barbarous, and were esteemed by them in turn as mendacious and unmanly.

In ecclesiastical matters also the differences were of long standing. These related to questions of jurisdiction between the two patriarchates. Up to the eighth century, the patriarchate of the West included a number of provinces on the eastern side of the Adriatic — Illyricum, Dacia, Macedonia, and Greece. But Leo the Isaurian, who probably foresaw that Italy would ere long cease to form part of his dominions, and was unwilling that these important territories should own spiritual allegiance to one who was not his subject, altered this arrangement, and transferred the jurisdiction over them to the Patriarch of Constantinople. Against this measure the bishops of Rome did not fail to protest, and demands for their restoration were made up to the time of the final schism. A further ecclesiastical question, which in part depended on this, was that of the Church of the Bulgarians. The prince Bogoris had swayed to and fro in his inclinations between the two churches, and had ultimately given his allegiance to that of the East; but the controversy did not end there. According to the ancient territorial arrangement the Danubian provinces were made subject to the archbishopric of Thessalonica, and that city was included within the Western patriarchate; and on this ground Bulgaria was claimed by the Roman see as falling within that area. The matter was several times pressed on the attention of the Greek Church, especially on the occasion of the council held at Constantinople in 879, but in vain. The Eastern prelates replied evasively, saying that to determine the boundaries of dioceses was a matter which belonged to the sovereign. The Emperor, for his part, had good reason for not yielding, for by so doing he would not only have admitted into a neighboring country an agency which would soon have been employed for political purposes to his disadvantage, but would have justified the assumption on which the demand rested, viz., that the pope had a right to claim the provinces which his predecessors had lost. Thus this point of difference also remained open, as a source of irritation between the two churches.

But behind these questions another of far greater magnitude was coming into view, that of the papal supremacy. From being in the first instance the head of the Christian church in the old Imperial city, and afterward Patriarch of the West, and primus inter pares in relation to the other spiritual heads of Christendom, the bishop of Rome had gradually claimed, on the strength of his occupying the cathedra Petri, a position which approximated more and more to that of supremacy over the whole Church. This claim had never been admitted in the East, but the appeals which were made from Constantinople to his judgment and authority, both at the time of the iconoclastic controversy and subsequently, lent some countenance to its validity.

| Master List | Next—> |

Joseph Deharbe begins here.

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Like!! Great article post.Really thank you! Really Cool.