Not only did the Federalists put him aside by degrees, but their faultfinding with his actions and omissions began here and there to partake of the tone of the most odious attacks made by the Republicans on his policy.

Continuing Jefferson’s Party Defeats the Federalists,

with a selection from Constitutional and Political History of the United States by Hermann Von Holst published in 1891. This selection is presented in 6.5 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Jefferson’s Party Defeats the Federalists.

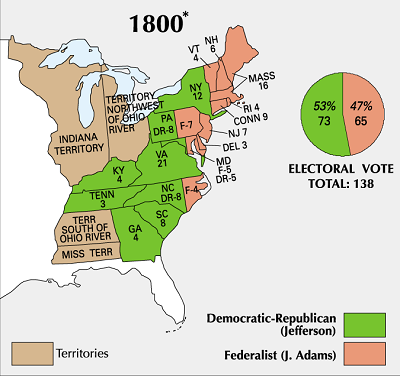

Time: 1800

Place: Washington, D.C.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Jefferson could not only use such language without danger, but it was unquestionably the best key in which he could have spoken, although the extreme Republicans would have much preferred to listen to a valictis! He had asserted as early as the spring of 1796, that “the whole landed interest,” and therefore a large majority of the people, belonged to the Republican party. There is now little difference of opinion on the point that Jefferson would immediately have followed Washington in the Presidential chair, if the electors had been nothing but the men of straw into which they afterward degenerated. But even if this could be rightly questioned, it would not yet follow that the majority of the people were then really inclined to the Federal party. The Republicans were far inferior to the Federalists in the numbers and the ability of their leaders; and, moreover, the great moneyed interests of the Northern States were the cornerstone of the Federal party. These were two elements which might very well keep them in power awhile longer, even if the majority of the people were in reality more attached to the principles of their antagonists. But they were not a support on which they could establish lasting rule. In a democratic republic, the political influence of the moneyed interests, when they have not attained the immense proportions they have in the America of to-day, is, as a rule, very limited, and that of talent is very frequently still smaller.

Hamilton’s lead was followed as long as the pressure of necessity was felt. But as soon as the most difficult labor of organization was done, his superiority became one of the greatest obstacles which stood in the way of his public activity. Not only did the Federalists put him aside by degrees, but their faultfinding with his actions and omissions began here and there to partake of the tone of the most odious attacks made by the Republicans on his policy. This was a sign of the times which deserved the most earnest consideration. When in a political party, in a popular state, a breach occurs between its founders and the masses that compose it, its days are, as a rule, numbered. If the breach takes place after the essential idea on which the party was founded has been realized, it will not, and cannot, be long survived.

This one essential idea, which constituted the real spark of vitality in the Federalist party, had been realized before the end of Washington’s second term as President, and the existence of the work as well secured as was possible under the circumstances. The force which moved the pendulum in its forward motion was exhausted. And if it did not begin its backward course immediately, but seemed to stand for a moment in suspense, it was because an accidental force acted upon it from without. The prolongation of the supremacy of the Federal party was due mainly to the unhealthy attitude assumed by the Anti-Federalists toward France. When the fruits of this began to be reaped in the transactions under the government of the Directory, the power of the Federalists, which was then declining, at once mounted to its zenith. The Congressional elections of 1797 were very favorable to them. The value of this success, however, must not be overestimated, as it was owing to a question of external politics. Only in case foreign politics, by the outbreak of war, should be kept most prominently in the foreground, could they hope that their success would obtain a more lasting character. But the quarrel between France and the United States had reached its height with the “X. Y. Z.” affair * and with Gerry’s return. When Adams, contrary to a former solemn assurance, resolved to send a new embassy to France, the Republicans soon regained the ground they had lost; for the attitude of the people toward questions of home politics remained essentially unaltered.

[* The X. Y. 2. Mission, an American embassy to France in 1797, consisting of C. C. Pinckney, John Marshall, and Elbridge Gerry. An attempt was made by three French agents (disguised as X., Y., and Z.) to bribe them.—ED.]

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Hermann Von Holst begins here. Thomas Jefferson begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.