The victory of the Republicans did not by any means produce the revolution in internal politics which was to be expected.

Continuing Jefferson’s Party Defeats the Federalists,

with a selection from Constitutional and Political History of the United States by Hermann Von Holst published in 1891. This selection is presented in 6.5 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Jefferson’s Party Defeats the Federalists.

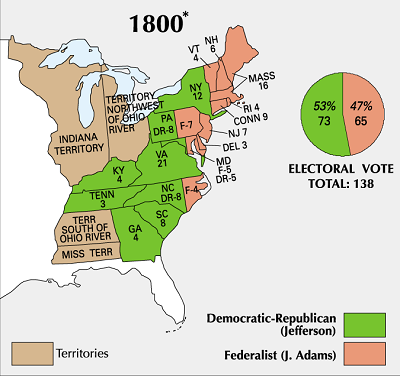

Time: 1800

Place: Washington, D.C.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Everyone was fully conscious of the magnitude of the crisis. Bayard wrote to Hamilton on March 8th concerning the last caucus of the Federalists: “All acknowledged that nothing but desperate measures remained, which several were disposed to adopt and but few were willing openly to disapprove. We broke up each time in confusion and discord, and the manner of the last ballot was arranged but a few minutes before the ballot was given.” Some years later he repeated the assertion under oath, that there were some who thought it better to abide by their vote, and to remain without a President, rather than choose Jefferson. But reason and patriotism at length obtained the mastery. Bayard seems to have been the instrument of this decision.

How much Hamilton contributed to the defeat of the advocates of the va banquel it is not easy to estimate. Randolph, at the time a member of the House of Representatives, often expressed his conviction that the safety of the Republic was due to Hamilton. There was no difference of opinion in the two parties on this, that the victory of the stubborn Federalists would have seriously endangered the Republic.

One month before the balloting began we find the conviction prevalent among the Federalists that the Republicans would, under no circumstances, be satisfied with an interregnum or with the election of Burr. James Gunn, a Federal Senator from Georgia, wrote to Hamilton on January 9th: “On the subject of choosing a President some revolutionary opinions are gaining ground, and the Jacobins are determined to resist the election of Burr at every hazard. I am persuaded that the Democrats have taken their ground with the fixed resolution to destroy the Government rather than yield their point.”

The Republicans did not oppose this conviction, but declared it to be well founded with all the emphasis with which such declarations have always been made in America. Jefferson wrote to Monroe on February 15th, two days before the election: “If they (the Federalists) had been permitted to pass a law for putting the Government into the hands of an officer, they would certainly have prevented an election. But we thought it best to declare openly and firmly, one and all, that the day such an act was passed, the Middle States would arm, and that no such usurpation, even for a single day, should be submitted to. This first shook them, and they were completely alarmed at the resource for which we declared; to wit, a convention to reorganize the Government and to amend it.” Armed resistance, followed by a peaceful revolution; such was the last word of the Republicans. The Federalists rightly considered this ultimatum to be no vain threat. In a letter written the day after the election to Madison, Jefferson speaks of the “certainty” that legislative usurpation would have met with armed resistance. And Jefferson’s testimony is by no means the only evidence. Even the press began to treat the subject of “bella, horrida bella!” More than this; in Virginia, where the excitement was greatest, establishments had already been erected to supply the necessary arms, and even troops. John Randolph, in the speech already mentioned, had completely lifted the curtain that hung over this subject. Reliance was to be placed on Dark’s brigade, which had promised to take possession of the arms in the United States armory at Harper’s Ferry.

The idea of waging war on the Union with its own weapons is very old; the secessionists did nothing more than carry out the plan which the “fathers” of the Republic had considered as embodying the proper course under certain contingencies.

The victory of the Republicans did not by any means produce the revolution in internal politics which was to be expected. When the electoral vote had been made known, Jefferson, in the first transports of his joy over the victory, blew with all his might the trumpets of the opposition. He tendered Chancellor Livingston a place in his Cabinet, that he might be of some service in the “new establishment of Republicanism; I say for its new establishment, for hitherto we have only seen its travesty.” The stubborn resistance of the Federalists, which wounded his vanity not a little, increased his angry feeling against them. On February 18th he furnished Madison with an account of the election. He lays particular stress on the fact that the Federalists did not finally vote for him, but that there was an election only because a part of them abstained from voting, or only used blank ballots. “We consider this, therefore,” he says, “a declaration of war on the part of this band.”

These utterances are thoroughly in keeping with Jefferson’s preceding course, and with his words and actions toward the Federalists and their policy. Spite of this, however, his own future policy is not to be inferred from them. Hamilton did not fall into this error, because he was well acquainted with the main traits of Jefferson’s character, and estimated their relative value correctly, although his judgment on the whole may have been somewhat too severe. He therefore saw and foretold the character of Jefferson’s policy better than Jefferson himself could have done while under the influence of the excitement of the political campaign. Hamilton writes to Bayard, January 16, 1801: “Nor is it true that Jefferson is zealot enough to do anything in pursuance of his principles which will contravene his popularity or his interest. He is as likely as any man I know to temporize, to calculate what will be likely to promote his own reputation and advantage; and the probable result of such a temper is the preservation of systems, though originally opposed, which being once established could not be overturned without danger to the person who did it. To my mind, a true estimate of Mr. Jefferson’s character warrants the expectation of a temporizing rather than of a violent system.”

This judgment of Hamilton found its confirmation in the in augural address of the new President. In it Jefferson counsels that the rights of the minority should be held sacred, that a union in heart and soul should be brought about, and that an effort should be made to do away with despotic political intolerance as religious intolerance had already been done away with. “We have called by different names brothers of the same principle. We are all Republicans -— we are all Federalists.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Hermann Von Holst begins here. Thomas Jefferson begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.