We have now to consider the doctrinal questions which were in dispute between the two churches.

Continuing Orthodox, Catholics Split,

with a selection from The Church and the Eastern Empire by Henry F. Tozer published in 1888. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. This selection is presented in 4 installments, each one 5 minutes long.

Previously in Orthodox, Catholics Split.

Time: 1054

Place: Rome and Constantinople

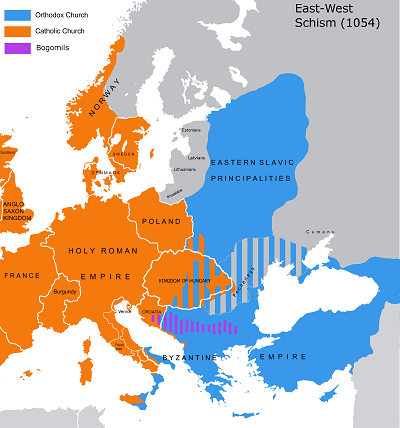

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

On the removal of his rival, so strangely did opinion sway to and fro at this time in the empire, the current of feeling set strongly in favor of the learned exile. He was recalled, and his reinstatement was ratified by a council (879). But with the death of Basil the Macedonian (886), he again fell from power, for the successor of that Emperor, Leo the Philosopher, ignominiously removed him, in order to confer the dignity on his brother Stephen. He passed the remainder of his life in honorable retirement, and by his death the chief obstacle in the way of reconcilement with the Roman Church was removed. It is consoling to learn, when reading of the unhappy rivalry of the two men so superior to the ordinary run of Byzantine prelates, that they never shared the passions of their respective partisans, but retained a mutual regard for one another.

We have now to consider the doctrinal questions which were in dispute between the two churches. Far the most important of these was that relating to the addition of the Filioque clause to the Nicene Creed. In the first draft of the Creed, as promulgated by the council of Nicaea, the article relating to the Holy Spirit ran simply thus: “I believe in the Holy Ghost.” But in the Second General Council, that of Constantinople, which condemned the heresy of Macedonius, it was thought advisable to state more explicitly the doctrine of the Church on this subject, and among other affirmations the clause was added, “who proceedeth from the Father.” Again, at the next general council, at Ephesus, it was ordered that it should not be lawful to make any addition to the Creed, as ratified by the Council of Constantinople. The followers of the Western Church, however, generally taught that the Spirit proceeds from the Son as well as from the Father, while those of the East preferred to use the expression, “the Spirit of Christ, proceeding from the Father, and receiving of the Son,” or, “proceeding from the Father through the Son.” It was in the churches of Spain and France that the Filioque clause was first introduced into the Creed and thus recited in the services, but the addition was not at once approved at Rome. Pope Leo III, early in the ninth century, not only expressed his disapproval of this departure from the original form, but, in order to show his sense of the importance of adhering to the traditional practice, caused the Creed of Constantinople to be engraved on silver plates, both in Greek and Latin, and thus to be publicly set forth in the Church. The first pontiff who authorized the addition was Nicholas I, and against this Photius protested, both during the lifetime of that Pope and also in the time of John VIII, when it was condemned by the council held at Constantinople in 879, which is called by the Greeks the Eighth General Council. It is clear from what we have already seen that Photius was prepared to seize on any point of disagreement in order to throw it in the teeth of his opponents, but in this matter the Eastern Church had a real grievance to complain of. The Nicene Creed was to them what it was not to the Western Church, their only creed, and the authority of the councils, by which its form and wording were determined, stood far higher in their estimation. To add to the one and to disregard the other were, at least in their judgment, the violation of a sacred compact.

The other question, which, if not actually one of doctrine, had come to be regarded as such, was that of the azyma, that is, the use of unfermented bread in the celebration of the eucharist. As far as one can judge from the doubtful evidence on the subject, it seems probable that ordinary, that is, leavened bread, was generally used in the church for this purpose until the seventh or eighth century, when unleavened bread began to be employed in the West, on the ground that it was used in the original institution of the sacrament, which took place during the Feast of the Passover. In the Eastern Church this change was never admitted. It seems strange that so insignificant a matter of observance should have been erected into a question of the first importance between the two communions, but the reason of this is not far to seek. The fact is that, whereas the weighty matters of dispute — the doctrine of the Procession of the Holy Spirit, and the papal claims to supremacy — required some knowledge and reflection in order rightly to understand their bearings, the use of leavened or unleavened bread was a matter within the range of all, and those who were on the lookout for a ground of antagonism found it here ready to hand.

In the story of the conversion of the Russian Vladimir we are told that the Greek missionary who expounded to him the religious views of the Eastern Church, when combating the claims of the emissaries of the Roman communion, remarked: “They celebrate the mass with unleavened bread; therefore they have not the true religion.” Still, even Photius, when raking together the most minute points of difference between him and his adversaries, did not introduce this one. It was reserved for a hot-headed partisan at a later period to bring forward as a subject of public discussion.

This was Michael Cerularius, Patriarch of Constantinople, with whose name the Great Schism will forever be associated.

The circumstances which led up to that event are as follows: For a century and a half from the death of Photius the controversy slumbered, though no advance was made toward an understanding with respect to the points at issue. In Italy, and even at Rome, churches and monasteries were tolerated in which the Greek rite was maintained, and similar freedom was allowed to the Latins resident in the Greek empire. But this tacit compact was broken in 1053 by the patriarch Michael, who, in his passionate antagonism to everything Western, gave orders that all the churches in Constantinople in which worship was celebrated according to the Roman rite should be closed. At the same time — aroused, perhaps, in some measure by the progress of the Normans in conquering Apulia, which tended to interfere with the jurisdiction still exercised by the Eastern Church in that province — he joined with Leo, the archbishop of Achrida and metropolitan of Bulgaria, in addressing a letter to the Bishop of Trani in Southern Italy, containing a violent attack on the Latin Church, in which the question of the azyma was put prominently forward.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Henry F. Tozer begins here. Joseph Deharbe begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.