This series has nine easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Origins of Russian Serfdom.

Introduction

By the act that freed the serfs in Russia, Alexander II, to whom it was in great measure due, obtained a place of unusual honor among the sovereigns that have ruled his nation. It was the grand achievement of Alexander’s reign, and caused him to be hailed as one of the world’s liberators. The importance of this event in Russian history is not diminished by the subsequent history of oppression and communism. In 1888 Stepniak, the Russian author and reformer, declared that emancipation had utterly failed to realize the ardent expectations of its advocates and promoters, had failed to improve the material condition of the former serfs, who on the whole were worse off than before emancipation. The same assertion has been made with respect to the emancipation of slaves in the United States, but in neither case does the objection invalidate the historical significance of an act that formally liberated millions of human beings from hereditary and legalized bondage. In both cases freedom meant opportunity for future improvement.

In the two views here presented, the subject of the emancipation in Russia is considered in various aspects. Andrew D. White’s account, being that of an American scholar and diplomatist familiar with the history and people of Russia through his residence at St. Petersburg, is of peculiar value, embodying the most intelligent foreign judgment. White’s synopsis covers the entire subject of the serf system from its beginning to its overthrow. Nikolai Turgenieff, the Russian historian, writing while the emancipation act was bearing its first fruits, describes its workings and effects as observed by one intimately connected with the serfs and the movement that resulted in their freedom.

The selections are from:

- The Development and Overthrow of the Russian Serf System in The Atlantic Monthly Magazine, Volume X by Andrew D. White published in 1862.

- Letter in The Nation Magazine, Volume I by Nikolai Turgenieff published in 1865.

There’s 8 installments by Andrew D. White and 1 installment by Nikolai Turgenieff. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

We begin with Andrew D. White. He was a historian who co-founded Cornell University. He served as a U.S. diplomat to Russia.

Time: 1861

Place: Russia

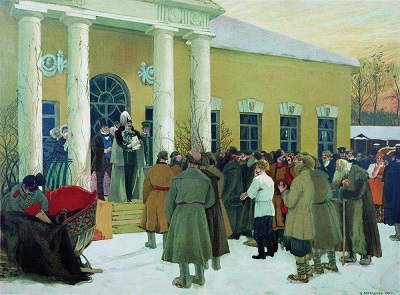

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Close upon the end of the fifteenth century the Muscovite ideas of right were subjected to the strong mind of Ivan the Great and compressed into a code. Therein were embodied the best processes known to his land and time: for discovering crime, torture and trial by battle; for punishing crime, the knout and death.

But hidden in this tough mass was one law of greater import than others. Thereby were all peasants forbidden to leave the lands they were then tilling, except during the eight days before and after St. George’s Day. This provision sprang from Ivan’s highest views of justice and broadest views of political economy; the nobles received it with plaudits, which have found echoes even in these days; the peasants received it with no murmurs which history has found any trouble in drowning.

Just one hundred years later upon the Muscovite throne, as nominal Czar, sat the weakling Feodor I; but behind the throne stood, as real Czar, hard, strong Boris Godunoff. Looking forward to Feodor’s death, Boris made ready to mount the throne; and he saw — what all other “Mayors of the Palace” climbing into the places of faineant kings have seen — that he must link to his fortunes the fortunes of some strong body in the nation; he broke, however, from the general rule among usurpers — bribing the church — and determined to bribe the nobility.

The greatest grief of the Muscovite nobles seemed to be that the peasants could escape from their oppression by the emigration allowed on St. George’s Day. Boris saw his opportunity: he cut off the privilege of St. George’s Day, and the peasant was fixed to the soil forever. No Russian law ever directly enslaved the peasantry, but, through this decree of Boris, the lord who owned the soil came to own the peasants, just as he owned its immovable boulders and ledges. To this the peasants submitted; but history has not been able to drown their sighs over this wrong; their proverbs and ballads make St. George’s Day representative of all ill-luck and disappointment.

A few years later Boris made another bid for oligarchic favor. He issued a rigorous fugitive-serf law, and even wrenched liberty from certain free peasants who had entered service for wages before his edicts. This completed the work, and Russia, which never had had the benefits of feudalism, had now fastened upon her feudalism’s worst curse, a serf caste, bound to the glebe.

The great good things done by Peter the world knows by heart. The world knows well how he tore his way out of the fetichism of his time; how, despite ignorance and unreason, he dragged his nation after him; how he dowered the nation with things and thoughts that transformed it from a petty Asiatic horde to a great European Power.

We were present a few years since when one of those lesser triumphs of his genius was first unfolded. It was in that room at the Hermitage — adjoining the Winter Palace — set apart for the relics of Peter. Our companions were two men noted as leaders in American industry — one famed as an inventor, the other famed as a champion of inventors’ rights.

Suddenly from the inventor, pulling over some old dust-covered machines in a corner, came loud cries of surprise. The cries were natural indeed. In that heap of rubbish he had found a lathe for turning irregular forms, and a screw-cutting engine once used by Peter himself: specimens of his unfinished work were still in them. They had lain there unheeded a hundred fifty years; their principle had died with Peter and his workmen; and not many years since, they were reinvented in America, and gave their inventors fame and fortune. At the late Paris Universal Exposition crowds flocked about an American lathe for copying statuary; and that lathe was, in principle, identical with this old, forgotten machine of Peter’s.

Yet, though Peter fought so well and thought so well, he made some mistakes which hang to this day over his country as bitter curses. For in all his plan and work to advance the mass of men was one supreme lack — lack of any account of the worth and right of the individual man. Lesser examples of this are seen in his grim jest at Westminster Hall — “What use of so many lawyers? I have but two lawyers in Russia, and one of those I mean to hang as soon as I return;” or when at Berlin, having been shown a new gibbet, he ordered one of his servants to be hanged in order to test it; or in his review of parade fights, when he ordered his men to use ball, and to take the buttons off their bayonets.

Greater examples are seen in his Battle of Narva, when he threw away an army to learn his opponent’s game; in his building of St. Petersburg, where, in draining marshes, he sacrificed a hundred thousand men the first year. But the greatest proof of this great lack was shown in his dealings with the serf system. Serfage was already recognized in Peter’s time as an evil. Peter himself once stormed forth in protestations and invectives against what he stigmatized as “selling men like beasts; separating parents from children, husbands from wives; which takes place nowhere else in the world, and which causes many tears to flow.” He declared that a law should be made against it. Yet it was by his misguided hand that serfage was compacted into its final black mass of foulness.

| Master List | Next—> |

Nikolai Turgenieff begins here.

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.