Strong as Alexander showed himself by these words, he showed himself stronger by acts.

Continuing Russian Serfs Freed,

with a selection from The Development and Overthrow of the Russian Serf System in The Atlantic Monthly Magazine, Volume X by Andrew D. White published in 1862. This selection is presented in 8 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Russian Serfs Freed.

Time: 1861

Place: Russia

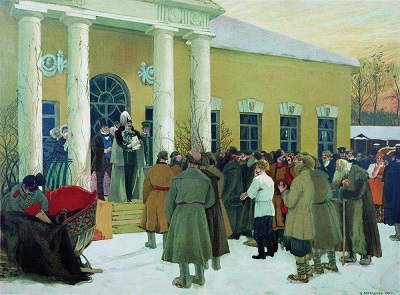

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The great man died. We saw his cold dead face, in the midst of crowns and crosses, very pale then, very powerless then. One might stare at him, then, as at a serf’s corpse; for he who had scared Europe during thirty years lay before us that day as a poor lump of chilled brain and withered muscle. And we stood by, when, amid chanting and flare of torches and roll of cannon, his sons wrapped him in his shroud of gold thread, and lowered him into the tomb of his fathers.

But there was shown in those days far greater tribute than the prayers of bishops or the reverence of ambassadors. Massed about the Winter Palace and the Fortress of Peter and Paul, stood thousands on thousands who, in far-distant serf-huts, had put on their best, had toiled wearily to the capital to give their last mute thanks to one who for years had stood between their welfare and their owners’ greed. Sad that he had not done more. Yet they knew that he had wished their freedom and loathed their wrongs; for that came up the tribute of millions.

The new Emperor, Alexander II, had never been hoped for as one who could light the nation from his brain; the only hope was that he might warm the nation somewhat from his heart. He was said to be of a weak, silken fibre. The strength of the family was said to be concentrated in his younger brother, Constantine. But soon came a day when the young Czar revealed to Europe not merely kindliness, but strength. While his father’s corpse was still lying within his palace, he received the diplomatic body. As the Emperor entered the audience-room he seemed feeble, indeed, for such a crisis. That fearful legacy of war seemed to weigh upon his heart; marks of plenteous tears were upon his face; Nesselrode, though old and bent and shrunk in stature, seemed stronger than his young master.

But as he began his speech it was seen that a strong man had mounted the throne. With earnestness he declared that he sorrowed over the existing war; but that, if the Holy Alliance had been broken, it was not through the fault of Russia. With bitterness he turned toward the Austrian minister, Esterhazy, and hinted at Russian services in 1848, and Austrian ingratitude. Calmly then, not as one who spoke a part but as one who announced a determination, he declared: “I am anxious for peace; but if the terms at the approaching congress are incompatible with the honor of my nation, I will put myself at the head of my faithful Russia and die sooner than yield.”

Strong as Alexander showed himself by these words, he showed himself stronger by acts. A policy properly mingling firmness and conciliation brought peace to Europe and showed him equal to his father; a policy mingling love of liberty with love of order brought the dawn of prosperity to Russia and showed him the superior of his father. The reforms now begun were not stinted as of old, but free and hearty. In rapid succession were swept away restrictions on telegraphic communication, on printing, on the use of the Imperial Library, on strangers entering the country, on Russians leaving the country. A policy in public works was adopted which made Nicholas’s greatest efforts seem petty; a vast network of railways was begun. A policy in commercial dealings with Western Europe was adopted, in which Alexander, though not apparently so imposing as Nicholas, was really far greater; he dared advance toward freedom of trade.

But soon rose again that great problem of old — that problem ever rising to meet a new autocrat, and, at each appearance, more dire than before — the serf question. The serfs in private hands now numbered more than twenty millions; above them stood more than a hundred thousand owners. The princely strength of the largest owners was best represented by a few men possessing over a hundred thousand serfs each, and, above all, by Count Scheremetieff, who boasted three hundred thousand. The luxury of the large owners was best represented by about four thousand men possessing more than a thousand serfs each. The pinching propensities of the small owners were best represented by fifty thousand men possessing fewer than twenty serfs each.

The serfs might be divided into two great classes. The first comprised those working under the old or corvée system, giving usually three days in the week to the tillage of the owner’s domain; the second comprised those working under the new or obrok system, receiving a payment fixed by the owner and assessed by the community to which the serfs belonged. The character of the serfs had been moulded by the serf system. They had a simple shrewdness, which, under a better system, had made them enterprising; but this quality soon degenerated into cunning and cheatery — the weapons which the hopelessly oppressed always use. They had a reverence for things sacred, which under a better system might have given the nation a strengthening religion; but they now stood among the most religious peoples on earth and among the least moral. To the picture of Our Lady of Kazan they were ever ready to burn wax and oil; to truth and justice they constantly omitted the tribute of mere common honesty. They kept the Church fasts like saints; they kept the Church feasts like satyrs.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Andrew D. White begins here. Nikolai Turgenieff begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.