At last, on the night of June 4th, the sepoy regiments at Cawnpore broke out in mutiny. They were driven to action by the same mad terror which had been manifested elsewhere.

Continuing The Sepoy Mutiny,

our selection from Short History of India and the Frontier States of Afghanistan, Nipal, and Burma by J. Talboys Wheeler published in 1884. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Sepoy Mutiny.

Time: June, 1857

Place: India

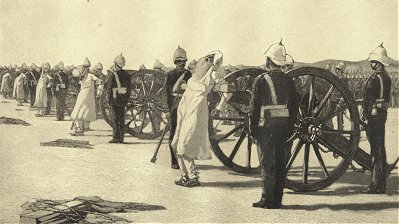

Public domain image from Wikipedia

The station of Cawnpore was commanded by Sir Hugh Wheeler, a distinguished general in the company’s service, who was verging on his seventieth year. He had spent fifty-four years in India, and had served only with native troops. He must have known the sepoys better than any other European in India. He had led them against their own countrymen under Lord Lake; against foreigners during the Afghan War, and against Sikhs during both campaigns in the Punjab.

The news of the revolt at Meerut threw the sepoys into a ferment at every military station in Hindustan. Rumors of mutiny or coming mutiny formed almost the only topic of conversation; yet in nearly every sepoy regiment the European officers put faith in their men, and fondly believed that, though the rest of the army might revolt, yet their own corps would prove faithful.

Such was eminently the case at Cawnpore, yet General Wheeler seems to have known better. While the European officers continued to sleep every night in the sepoy lines, the veteran made his preparations for meeting the coming storm.

European combatants were very few at Cawnpore, but European impedimenta were very heavy. Besides the wives and families of the regimental officers of the sepoy regiments, there was a large European mercantile community. Moreover, while the Thirty-Second Foot was quartered at Lucknow, the wives, families, and invalids of the regiment were living at Cawnpore. It was thus necessary to secure a place of refuge for this miscellaneous multitude of Europeans in the event of a rising of the sepoys. Accordingly, General Wheeler pitched upon some old barracks which had once belonged to a European regiment; and he ordered earthworks to be thrown up, and supplies of all kinds to be stored, in order to stand a siege. Unfortunately, there was fatal neglect somewhere; for when the crisis came the defenses were found to be worthless, while the supplies were insufficient for the besieged.

All this while the adopted son of the former peshwa * was living at Bithoor, about six miles from Cawnpore. His real name was Dandhu Panth, but he is better known as Nana Sahib. The British Government had refused to award him the absurd life pension of eighty thousand pounds sterling, which had been granted to his nominal father; but he had inherited at least half a million from the ex-peshwa; and he was allowed to keep six guns, to entertain as many followers as he pleased, and to live in half royal state in a castellated palace at Bithoor. He continued to nurse his grievance with all the pertinacity of a Mahratta; but at the same time he professed a great love for European society, and was profuse in his hospitalities to English officers. He was popularly known as the Raja of Bithoor.

[* Formerly a chief of the Mahrattas. — Ed.]

When the news arrived of the revolt at Meerut on May 10th, Nana was loud in his professions of attachment to the English. He engaged to organize fifteen hundred fighting men to act against the sepoys in the event of an outbreak. On May 21st, there was an alarm. European women and families, with all European non-combatants, were removed into the barracks, and General Wheeler actually accepted from Nana the help of two hundred Mahrattas and two guns to guard the treasury. The alarm, however, soon blew over, and Nana took up his abode at the civil station of Cawnpore, as a proof of the sincerity of his professions.

At last, on the night of June 4th, the sepoy regiments at Cawnpore broke out in mutiny. They were driven to action by the same mad terror which had been manifested elsewhere. They cared nothing for the Mogul, nothing for the pageant King at Delhi; but they had been panic-stricken by extravagant stories of coming destruction. It was whispered among them that the parade-ground was undermined with powder, and that Hindus and Mahometans were to be assembled on a given day and blown into the air. Intoxicated with fear and bhang, they rushed out in the darkness, yelling, shooting, and burning according to their wont; and when their excitement was somewhat spent, they marched off toward Delhi.

Sir Hugh Wheeler could do nothing. He might have retreated with the whole body of Europeans from Cawnpore to Allahabad; but there had been a mutiny at Allahabad, and, moreover, he had no means of transport. Subsequently he heard that the mutineers had reached the first stage on the road to Delhi, and consequently he saw no ground for alarm.

Meanwhile the brain of Nana Sahib had been turned by wild dreams of vengeance and sovereignty. He thought not only to wreak his malice upon the English, but to restore the extinct Mahratta Empire, and reign over Hindustan as the representative of the forgotten peshwas. The stampede of the sepoys to Delhi was fatal to his mad ambition. He overtook the mutineers, dazzled them with fables of the treasures in Wheeler’s entrenchment, and brought them back to Cawnpore to carry out his vindictive and visionary schemes.

At early morning on Saturday, June 6th, General Wheeler received from Nana a letter announcing that he was about to attack the entrenchment. The veteran was taken by surprise, but at once ordered all the European officers to join the party in the barracks and prepare for the defense. But the mutineers were in no hurry for the advance. They preferred booty to battle, and turned aside to plunder the cantonment and city, murdering every Christian that came in their way, not sparing the houses of their own countrymen. They appropriated all the cannon and ammunition in the magazine by way of preparation for the siege; but some were wise enough to desert the rebel army and steal to their homes with their ill-gotten spoil.

About noon the main body of the mutineers, swelled by the numerous retainers of Nana, got their guns into position, and opened fire on the entrenchment. For nineteen days — from June 6th to the 25th — the garrison struggled manfully against a raking fire and fearful odds, amid scenes of suffering and bloodshed that cannot be recalled without a shudder.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.