This series has eight easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: The Greased Cartridges.

Introduction

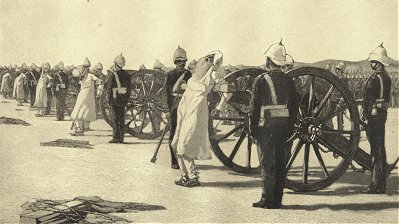

The rebellion, or “mutiny’ as the British called it, of a part of India was noteworthy in two respects. First, that it was so unique. A smaller country (Britain) occupied and ruled a much larger one (India) and one that was advanced as India was for a long time wilh civil unrest that was unusually lower than one would expect. If this were to be expected, then why did not Britain occupy and rule China or Japan? Second, was the severity of the conflict. Execution by cannon? Where else does one read of this? Among the evils of terror executions, this is unrivaled. Even powers like the Nazi’s and today’s ISIS does not do this, or at least did not do this on a widespread basis like the British did this at the end of this conflict.

Clearly there was some special and unique attitudes at play here.

From the time when Warren Hastings, the first English Governor-General of India, was sent to rule there (1774), the British power in that country grew steadily, and many annexations were made to the territory under its control. There were frequent wars with the French, England’s rivals in India, and with the natives in different Provinces that one after another were absorbed into the British possessions. The first serious menace against this growing power appeared in a native movement, the culmination of which is known as the “Indian” or “Sepoy Mutiny”.

The causes of this rising are traced to distrust and hatred of the British rulers — feelings that caused a ferment among the Hindus and Mohammedans of India, who suspected a design for suppressing their religions. The natives also became alarmed at the introduction of Western ideas and improvements — new methods of education, the steam-engine, the telegraph, etc. — portending to the Indian peoples the substitution of a foreign civilization for their own. The truth is that in attempting to abolish suttee and other ancient native customs, and to introduce more enlightened practices, the British Government was acting in the interest of general humanity.

The immediate provocation of the great mutiny among the sepoys or native troops in the British East-Indian service is well shown, and the entire story of the revolt is equally well told, by Mr. Wheeler. This author, while a secretary to the Government of India in the latter part of the nineteenth century, enjoyed peculiar advantages for study and research. These advantages he turned to account by writing an authoritative and interesting history of the land of his official residence.

This selection is from Short History of India and the Frontier States of Afghanistan, Nipal, and Burma by J. Talboys Wheeler published in 1884. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Wheeler was the great British historian of India and British rule there. He was also a government official there.

Time: 1857

Place: India

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Early in the year 1857, it is said, there were rumors of a coming danger to British rule in India. In some parts of the country chupatties, or cakes, were circulated in a mysterious manner from village to village. * Prophecies were also rife that in 1857 the East India Company’s raj [rule] would come to an end. Lord Canning has been blamed for not taking alarm at these proceedings; but something of the kind always had been going on in India. Cakes of cocoanuts are given away in solemn fashion; and as the villagers were afraid to keep them or eat them, the circulation went on to the end of the chapter. Then, again, holy men and prophets have always been common in India. They foretell pestilence and famine: the downfall of British rule, or the destruction of the whole world. They are often supposed to be endowed with supernatural powers and to be impervious to bullets; but these phenomena invariably disappear whenever they come in contact with Europeans, especially as all such characters are liable to be treated as vagrants without visible means of subsistence.

[* The form of the cake conveyed information that an insurrection was in preparation — an old custom — understood by the natives. — ED.]

One dangerous story, however, got abroad in the early part of 1857, which ought to have been stopped at once, and for which the military authorities were wholly and solely to blame. The Enfield rifle was being introduced; it required new cartridges, which in England were greased with the fat of beef or pork. The military authorities in India, with strange indifference to the prejudices of sepoys, ordered the cartridges to be prepared at Calcutta in like manner; forgetting that the fat of pigs was hateful to the Mahometans, while the fat of cows was still more horrible in the eyes of the Hindus.

The excitement began at Barrackpur, sixteen miles from Calcutta. At this station, there were four regiments of sepoys, and no Europeans except the regimental officers. One day a low-caste native, known as a lascar, asked a Brahmin sepoy for a drink of water from his brass pot. The Brahmin refused, as it would defile his pot. The lascar retorted that the Brahmin was already defiled by biting cartridges which had been greased with cow’s fat. This vindictive taunt was based on truth. Lascars had been employed at Calcutta in preparing the new cartridges, and the man was possibly one of them. The taunt created a wild panic at Barrackpur. Strange to say, however, none of the new cartridges had been issued to the sepoys; and had this been promptly explained to the men, and the sepoys left to grease their own cartridges, the alarm might have died out. But the explanation was delayed until the whole of the Bengal army was smitten with the groundless fear; and then, when it was too late, the authorities protested too much, and the terror-stricken sepoys refused to believe them.

The sepoys had proved themselves brave under fire, and loyal to their salt in sharp extremities; but they are the most credulous and excitable soldiery in the world. They regarded steam and electricity as so much magic; and they fully believed that the British Government was binding India with chains, when it was only laying down railway lines and telegraph wires. The Enfield rifle was a new mystery; and the busy brains of the sepoys were soon at work to divine the motive of the English in greasing cartridges with cow’s fat. They had always taken to themselves the sole credit of having conquered India for the company; and they now imagined that the English wanted them to conquer Persia and China. Accordingly, they suspected that Lord Canning was going to make them as strong as Europeans by destroying caste, forcing them to become Christians, and making them eat beef and drink beer.

The story of the greased cartridges, with all its absurd embellishments, ran up the Ganges and Jumna to Benares, Allahabad, Agra, Delhi, and the great cantonment at Meerut; while another current of lies ran back again from Meerut to Barrackpur. It was noised abroad that the bones of cows and pigs had been ground into powder, and thrown into wells and mingled with flour and butter, in order to destroy the caste of the masses and convert them to Christianity.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.