Today’s installment concludes The Sepoy Mutiny,

our selection from Short History of India and the Frontier States of Afghanistan, Nipal, and Burma by J. Talboys Wheeler published in 1884.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of eight thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Sepoy Mutiny.

Time: September, 1857

Place: India

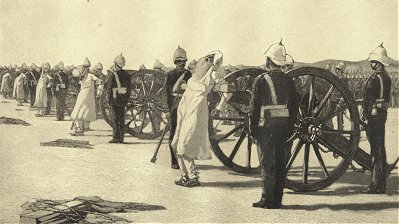

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Thus, fell the imperial city; captured by the army under Brigadier Wilson before the arrival of any of the reinforcements from England. The losses were heavy. From the beginning of the siege to the close, the British army at Delhi had nearly four thousand killed and wounded. The casualties on the side of the rebels were never estimated. Two bodies of sepoys broke away from the city and fled down the valleys of the Jumna and Ganges, followed by two flying columns under Brigadiers Greathed and Showers. But the great mutiny and revolt at Delhi had been stamped out, and the flag of England waved triumphantly over the capital of Hindustan.

The capture of Delhi, in September, 1857, was the turning-point in the sepoy mutinies. The revolt was crushed beyond redemption; the rebels were deprived of their head center; and the Mogul King was a prisoner at the mercy of the power whom he had defied. But there were still troubles in India. Lucknow was still beleaguered by a rebel army, and insurrections still ran riot in Oudh and Rohilkhand.

In the middle of August General Havelock had fallen back on Cawnpore, after the failure of his first campaign for the relief of Lucknow. Five weeks afterward Havelock made a second attempt under better auspices. Sir Colin Campbell had arrived at Calcutta as Commander-in-Chief. Sir James Outram had come up to Allahabad. On September 16th, while the British troops were storming the streets of Delhi, Outram joined Havelock and Neill at Cawnpore with fourteen hundred men. As senior officer, he might have assumed the command; but with generous chivalry the “Bayard of India” waived his rank in honor of Havelock.

On September 20th, General Havelock crossed the Ganges into Oudh at the head of twenty-five hundred men. The next day he defeated a rebel army and put it to flight, while four of the enemy’s guns were captured by Outram at the head of a body of volunteer cavalry. On the 23d Havelock routed a still larger rebel force which was strongly posted at a garden in the suburbs of Lucknow, known as the “Alumbagh.” He then halted to give his soldiers a day’s rest. On the 25th he was cutting his way through the streets and lanes of the city of Lucknow — running the gauntlet of a deadly and unremitting fire from the houses en both sides of the streets, and also from guns which commanded them. On the evening of the same day he entered the British intrenchments; but in the moment of victory a chance shot carried off the gallant Neill.

The defense of the British residency at Lucknow is a glorious episode in the national annals. The fortitude of the beleaguered garrison was the admiration of the world. The women nursed the wounded and performed every womanly duty with self-sacrificing heroism; and when the fight was over they received the well-merited thanks of Her Majesty Queen Victoria.

During four long months, the garrison had known nothing of what was going on in the outer world. They were aware of the advance and retreat of Havelock, and that was all. At last, on September 23d, they heard the booming of the guns at the Alumbagh. On the morning of the 25th they could see something of the growing excitement in the city; the people abandoning their houses and flying across the river. Still the guns of the rebels kept up a heavy cannonade upon the residency, and volleys of musketry continued to pour upon the besieged from the loopholes of the besiegers. But soon the firing was heard from the city; the welcome sounds came nearer and nearer. The excitement of the garrison grew beyond control. Presently the relieving force was seen fighting its way toward the residency. Then the pent-up feelings of the garrison burst forth in deafening cheers; and wounded men in hospital crawled out to join in the chorus of welcome. Then followed personal greetings as officers and men came pouring in. Hands were frantically shaken on all sides. Rough-bearded soldiers took the children from their mothers’ arms, kissed them with tears rolling down their cheeks, and thanked God that they had come in time to save them from the fate of the sufferers at Cawnpore.

Thus, after a siege of nearly four months Havelock succeeded in relieving Lucknow. But it was a reinforcement rather than a relief, and was confined to the British residency. The siege was not raised; and the city of Lucknow remained two months longer in the hands of the rebels. Sir James Outram assumed the command, but was compelled to keep on the defensive. Meanwhile reinforcements were arriving from England. In November Sir Colin Campbell reached Cawnpore at the head of a considerable army. He left General Windham with two thousand men to take charge of the intrenchment at Cawnpore, and then advanced against Lucknow with five thousand men and thirty guns. He carried several of the enemy’s positions, cut his way to the residency, and at last brought away the beleaguered garrison, with all the women and children. But not even then could he disperse the rebels and reoccupy the city. Accordingly, he left Outram at the head of four thousand men in the neighborhood of Lucknow, and then returned to Cawnpore.

On November 24th, the day after leaving Lucknow, General Havelock was carried off by dysentery, and buried in the Alumbagh. His death spread a gloom over India, but by this time his name had become a household word wherever the English language was spoken. In the hour of surprise and panic, as successive stories of mutiny and rebellion reached England, and culminated in the revolt at Delhi and massacre at Cawnpore, the victories of Havelock revived the drooping spirits of the British nation, and stirred up all hearts to glorify the hero who had stemmed the tide of disaffection and disaster. The death of Havelock, following the story of the capture of Delhi, and told with the same breath that proclaimed the deliverance at Lucknow, was received in England with a universal sorrow that will never be forgotten so long as men are living who can recall the memory of the “Mutiny of Fifty-seven.”

The subsequent history of the sepoy revolt is little more than a detail of the military operations of British troops for the dispersion of the rebels and restoration of order and law. Sir Colin Campbell * — later made Baron Clyde of Clydesdale — undertook a general campaign against the rebels in Oudh and Rohilkhand, and restored order and law in those disaffected Provinces; while Sir James Outram drove the rebels out of Lucknow, and reestablished British sovereignty in the capital of Oudh.

[* Died at Chatham, England, August 14, 1863. — ED.]

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The Sepoy Mutiny by J. Talboys Wheeler from his book Short History of India and the Frontier States of Afghanistan, Nipal, and Burma published in 1884. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The Sepoy Mutiny here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.