The highway from Calcutta to Delhi was blocked up by mutiny and insurrection; and every European soldier sent up from Calcutta was stopped for the relief of Benares, Allahabad, Cawnpore, or Lucknow.

Continuing The Sepoy Mutiny,

our selection from Short History of India and the Frontier States of Afghanistan, Nipal, and Burma by J. Talboys Wheeler published in 1884. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Sepoy Mutiny.

Time: September, 1857

Place: India

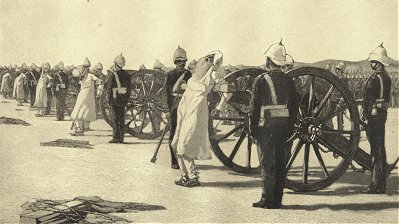

Public domain image from Wikipedia

During the four months that followed the revolt at Delhi on May 11th, all political interest was centered at the ancient capital of the sovereigns of Hindustan. The public mind was occasionally distracted by the current of events at Cawnpore and Lucknow, as well as at other stations which need not be particularized; but so long as Delhi remained in the hands of the rebels the native princes were bewildered and alarmed; and its prompt recapture was deemed of vital importance to the prestige of the British Government and the reestablishment of British sovereignty in Hindustan. The Great Mogul had been little better than a mummy for more than half a century; and Bahadur Shah was a mere tool and puppet in the hands of rebel sepoys; nevertheless, the British Government had to deal with the astounding fact that the rebels were fighting under his name and standard, just as Afghans and Mahrattas had done in the days of Ahmed Shah Durani and Mahadaji Sindhia. To make matters worse, the roads to Delhi were open from the south and east; and nearly every outbreak in Hindustan was followed by a stampede of mutineers to the old capital of the Moguls.

Meanwhile, in the absence of railways, there were unfortunate delays in bringing up troops and guns to stamp out the fires of rebellion at the head center. The highway from Calcutta to Delhi was blocked up by mutiny and insurrection; and every European soldier sent up from Calcutta was stopped for the relief of Benares, Allahabad, Cawnpore, or Lucknow. But the possession of the Punjab at this crisis proved to be the salvation of the empire. Sir John Lawrence, Chief Commissioner in the Punjab, was called upon for almost superhuman work; to maintain order in a conquered province; to suppress mutiny and disaffection among the very sepoy regiments from Bengal that were supposed to garrison the country; and to send reinforcements of troops and guns, and supplies of all descriptions, to the siege of Delhi. Fortunately, the Sikhs had been only a few short years under British administration; they had not forgotten the miseries that prevailed under the native Government, and could appreciate the many blessings they enjoyed under British rule. They were stanch to the British Government, and eager to be led against the rebels. In some cases, terrible punishment was meted out to mutinous Bengal sepoys within the Punjab, but the Imperial interests at stake were sufficient to justify every severity, although all must regret the painful necessity that called for such extreme measures.

On June 8th, about a month after the revolt at Delhi, Sir Henry Barnard took the field at Alipur, about ten miles from the rebel capital. He defeated an advance division of the enemy, and then marched to the Ridge and reoccupied the old cantonment which had been abandoned on May 11th. So far it was clear that the rebels were unable to do anything in the open field, although they might fight bravely under cover. They numbered about thirty thousand strong; they had a very powerful artillery and ample stores of ammunition, while there was an abundance of provisions within the city throughout the siege.

In the middle of August, Brigadier John Nicholson, one of the most distinguished officers of the time, came up from the Punjab with a brigade and siege-train. On September 4th, a heavy train of artillery was brought in from Firozpur. The British force on the Ridge now exceeded eight thousand men. Hitherto the artillery had been too weak to attempt to breach the city walls; but now fifty-four heavy guns were brought into position and the siege began in earnest. From September 8th to 12th four batteries poured in a constant storm of shot and shell; number one was directed against the Cashmere bastion, number two against the right flank of the Cashmere bastion, number three against the Water bastion, and number four against the Cashmere and Water gates and bastions. On September 13th, the breaches were declared to be practicable, and the following morning was fixed for the final assault upon the doomed city.

At three o’clock in the morning of September 14th three assaulting columns were formed in the trenches, while a fourth was kept in reserve. The first column was led by Brigadier Nicholson; the second by Brigadier Jones; the third by Colonel Campbell; and the fourth, or reserve, by Brigadier Longfield.

The powder-bags were laid at the Cashmere gate by Lieutenants Home and Salkeld. The explosion followed, and the third column rushed in, and pushed toward the Jumna Musjid. Meanwhile the first column under Nicholson escaladed the breaches near the Cashmere gate, and pushed along the ramparts toward the Kabul gate, carrying the several bastions in the way. Here it was met by the second column under Brigadier Jones, who had escaladed the breach at the Water bastion.

The advancing columns were met by a ceaseless fire from terraced houses, mosques, and other buildings; and John Nicholson, the hero of the day, while attempting to storm a narrow street near the Kabul gate, was struck down by a shot and mortally wounded. Then followed six days of desperate warfare. No quarter was given to men with arms in their hands; but women and children were spared, and only a few of the peaceable inhabitants were sacrificed during the storm.

On September 20th, the gates of the old fortified palace of the Moguls were broken open, but the royal inmates had fled. No one was left but a few wounded sepoys and fugitive fanatics. The old King, Bahadur Shah, had gone off to the great mausoleum without the city, known as the tomb of Humayun. It was a vast quadrangle raised on terraces and enclosed with walls. It contained towers, buildings, and monumental marbles in memory of different members of the once distinguished family, as well as extensive gardens, surrounded with cloistered cells for the accommodation of pilgrims.

On September 21st Captain Hodson rode to the tomb, arrested the King, and brought him back to Delhi with other members of the family, and lodged them in the palace. The next day he went again, with one hundred horsemen, and arrested two sons of the King in the midst of a crowd of armed retainers, and brought them away in a native carriage. Near the city, the carriage was surrounded by a tumultuous crowd; and Hodson, who was afraid of a rescue, shot both princes with his pistol, and placed their bodies in a public place for all men to see.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.