On July 7th, General Havelock left Allahabad for Cawnpore. The force at his disposal did not exceed two thousand men, Europeans and Sikhs.

Continuing The Sepoy Mutiny,

our selection from Short History of India and the Frontier States of Afghanistan, Nipal, and Burma by J. Talboys Wheeler published in 1884. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Sepoy Mutiny.

Time: July, 1857

Place: India

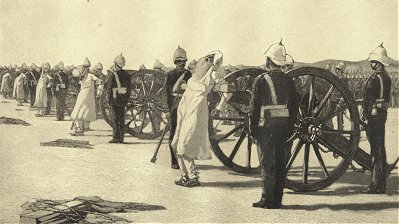

Public domain image from Wikipedia

General Havelock was a Queen’s officer of forty years’ standing; but he had seen more service in India than perhaps any other officer in Her Majesty’s Army. He had fought in the first Burma War, the Kabul War, the Gwalior campaign of 1843, and the Punjab campaign of 1845-1846. He was a pale, thin, thoughtful man; small in stature, but burning with the aspirations of a Puritan hero. Religion was the ruling principle of his life, and military glory was his master passion. He had just returned to India after commanding a division in the Persian War. Abstemious to a fault, he was able, in spite of his advancing years, to bear up against the heat and rain of Hindustan during the deadliest season of the year.

On July 7th, General Havelock left Allahabad for Cawnpore. The force at his disposal did not exceed two thousand men, Europeans and Sikhs. He had heard of the massacre at Cawnpore on June 27th, and burned to avenge it. On July 12th, he defeated a large force of mutineers and Mahrattas at Fathipur. On the 15th he inflicted two more defeats on the enemy. Havelock was now within twenty-two miles of Cawnpore, and he halted his men to rest for the night. But news arrived that the women and children were still alive at Cawnpore, and that Nana had taken the field with a large force to oppose his advance. Accordingly, Havelock marched fourteen miles that same night, and on the following morning, within eight miles of Cawnpore, the troops bivouacked beneath some trees.

On that same night, July 15th, the crowning atrocity was committed at Cawnpore. The rebels, who had been defeated by Havelock, returned to Nana with the tidings of their disaster. In revenge Nana ordered the slaughter of the two hundred women and children. The poor victims were literally hacked to death, or almost to death, with swords, bayonets, knives, and axús. Next morning the bleeding remains of dead and dying were dragged to a neighboring well and thrown in.

At two o’clock in the afternoon after the massacre the force under Havelock was again upon the march for Cawnpore. The heat was fearful; many of the troops were struck down by the sun, and the cries for water were continuous. But for two miles the column toiled on, and then came in sight of the enemy. Havelock had only one thousand Europeans and three hundred Sikhs; he had no cavalry, and his artillery was inferior. The enemy numbered five thousand men, armed and trained by British officers, strongly entrenched, with two batteries of guns of heavy caliber. Havelock’s artillery failed to silence the batteries, and he ordered the Europeans to charge with the bayonet. On they went in the face of a shower of grape, but the bayonet charge was as irresistible at Cawnpore as at Assaye. The enemy fought for a while like men in a death struggle. Nana Sahib was with them, but nothing is known of his exploits. At last they fled, and there was no cavalry to pursue them.

As yet nothing was known of the butchery of the women and children. Havelock halted for the night, and next morning marched his force into the station at Cawnpore. The men beheld the scene of the massacre, and saw the bleeding remains in the well. But the murderers had vanished, no one knew whither. Havelock advanced to Bithoor, and destroyed the palace of the Mahratta. Subsequently he was joined by General Neill, with reinforcements from Allahabad; and on July 20th he set on for the relief of Lucknow, leaving Cawnpore in charge of General Neill.

The defense of Lucknow against fifty-two thousand rebels was, next to the siege of Delhi, the greatest event in the mutiny. The whole Province of Oudh was in a blaze of insurrection. The talukdars were exasperated at the hard measure dealt out to them before the appointment of Sir Henry Lawrence as Chief Commissioner. Disbanded sepoys, returning to their homes in Oudh, swelled the tide of disaffection. Bandits that had been suppressed under British administration returned to their old work of robbery and brigandage. All classes took advantage of the anarchy to murder the money-lenders. Meanwhile the country was bristling with the fortresses of the talukdars; and the cultivators, deprived of the protection of the English, naturally flocked for refuge to the strongholds of their old masters.

The English, who had been lords of Hindustan ever since the beginning of the century, had been closely besieged in the residency at Lucknow ever since the final outbreak of May 30th. For nearly two months the garrison had held out with a dauntless intrepidity, while confidently waiting for reinforcements that seemed never to come. “Never surrender” had been from the first the passionate conviction of Sir Henry Lawrence; and the massacre at Cawnpore on June 27th impressed every soldier in the garrison with a like resolution. On July 2d the Muchi Bawen was abandoned, and the garrison and stores were removed to the residency. On July 4th Sir Henry Lawrence was killed by the bursting of a shell in a room where he lay wounded; and his dying counsel to those around him was, “Never surrender!”

On July 20th, the rebel force round Lucknow heard of the advance of General Havelock to Cawnpore, and attacked the residency in overwhelming force. They kept up a continual fire of musketry while pounding away with their heavy guns; but the garrison held their ground against shot and shell, and before the day was over the dense masses of assailants were forced to retire from the walls.

Between July 20th and 25th General Havelock began to cross the Ganges and make his way into Oudh territory; but he was unable to relieve Lucknow. His small force was weakened by heat and fever and reduced by cholera and dysentery; while the enemy occupied strong positions on both flanks. In the middle of August, he fell back upon Cawnpore.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.