This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Vast Territory for Speculation.

Introduction

Known under the various titles of the “Mississippi Scheme,” the “Mississippi Bubble,” and the “System,” the financial enterprise originated by John Law, under authority of the French government, proved to be the most disastrous economic experiment ever made by a civilized state.

Louis XIV ended his long reign in 1715, leaving his throne to his great-grandson, a child of five years, Louis XV. The impoverished country was in the hands of a regent, Philippe, Duke of Orléans, whose financial undertakings were all unfortunate. John Law, the son of a Scotch banker, was an adventurer and a gambler who yet became celebrated as a financier and commercial promoter. After killing an antagonist in a duel in London, he escaped the gallows by fleeing to the Continent, where he followed gaming and at the same time devised financial schemes which he proposed to various governments for their adoption. His favorite notion was that large issues of paper money could be safely circulated with small security.

Law offered to relieve Orléans from his financial troubles, and the Regent listened with favor to his proposals. In 1716 Law, with others, organized what he called the General Bank. It was ably managed, became popular, and by means of it Law successfully carried out his paper-currency ideas. His notes were held at a premium over those of the government, whose confidence was therefore won. Two years later Law’s institution was adopted by the state and became the Royal Bank of France. The further undertakings of this extraordinary “new light of finance,” the blowing and bursting of the great “bubble,” are recorded by Thiers, the French statesman and historian, himself eminent as his country’s chief financier during her wonderful recovery after the Franco-German War.

This selection is from The Mississippi Bubble – A Memoir of John Law by Louis Adolphe Thiers published in 1859. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Time: 1716

Place: Paris

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Law was always scheming to concentrate into one establishment his bank, the administration of the public revenues, and the commercial monopolies. He resolved, in order to attain this end, to organize, separately, a commercial company, to which he would add, one after another, different privileges in proportion to its success, and which he would then incorporate with the General Bank. Constructing thus separately each of the pieces of his vast machine, he proposed ultimately to unite them and form the grand whole, the object of his dreams and his ardent ambition.

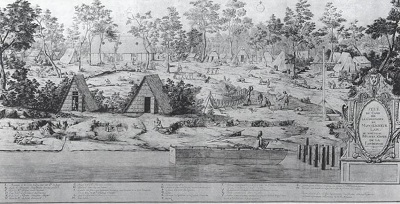

An immense territory, discovered by a Frenchman, in the New World, presented itself for the speculations of Law. The Chevalier de la Salle, the famous traveler of the time, having penetrated into America by Upper Canada, descended the river Illinois, arrived suddenly at a great river half a league wide, and, abandoning himself to the current, was borne into the Gulf of Mexico. This river was the Mississippi. The Chevalier de la Salle took possession of the country he had passed through for the King of France, and gave it the beautiful name of Louisiana.

There was much said of the magnificence and fertility of this new country, of the abundance of its products, of the richness of its mines, which were reported to be much more extensive than those of Mexico or Peru. Law, taking advantage of this current of opinion, projected a company which should unite the commerce of Louisiana with the fur trade of Canada. The Regent granted all he asked, by an edict given in August, 1717, fifteen months after the first establishment of the bank.

The new company received the title of the “West Indian Company.” It was to have the sovereignty of all Louisiana on the condition only of liege homage to the King of France, and of a crown of gold of thirty marks at the commencement of every new reign. It was to exercise all the rights of sovereignty, such as levying troops, equipping vessels-of-war, constructing forts, establishing courts, working mines, etc. The King relinquished to it the vessels, forts, and munitions of war which belonged to the Crozat Company, * and conceded, furthermore, the exclusive right of the fur trade of Canada. The arms of this sovereign company represented the effigy of an old river-god leaning upon a horn of plenty.

[* A company headed by Anthony Crozat. It was chartered in 1712, and formed a commercial monopoly in Louisiana. — ED.]

Law revolved in his mind many other projects relating to his Western company. He spoke, at first mysteriously, of the benefits which he was preparing for it. Associating with a large number of noblemen, whom his wit, his fortune, and the hope of considerable gains attracted around him, he urged them strongly to obtain for themselves some shares, which would soon rise rapidly in the market. He was himself soon obliged to buy some above par. The par value being five hundred francs, two hundred of them represented at par a sum of one hundred thousand francs. The price for the day being three hundred francs, sixty thousand francs were sufficient to buy two hundred shares. He contracted to pay one hundred thousand francs for two hundred shares at a fixed future time; this was to anticipate that they would gain at least two hundred francs each, and that a profit of forty thousand francs could be realized on the whole. He agreed, in order to make this sort of wager more certain, to pay the difference of forty thousand francs in advance, and to lose the difference if he did not realize a profit from the proposed transfer.

This was the first instance of a sale at an anticipated advance. This kind of trade consisted in giving “earnest-money” called a premium, which the purchaser lost if he failed to take the property. He who made the bargain had the liberty of rescinding it if he would lose more by adhering to it than by abandoning it. No advantage would accrue to Law for the possible sacrifice of forty thousand francs, unless at the designated time the shares had not been worth as much as sixty thousand francs, or three hundred francs each; for having engaged to pay one hundred thousand francs for what was worth only fifty thousand, for instance, he would suffer less to lose his forty thousand francs than to keep his engagement. But, evidently, if Law did wish by this method to limit the possible loss, he hoped nevertheless not to make any loss at all; and, on the contrary, he believed firmly that the two hundred shares would be worth at least the hundred thousand francs, or five hundred francs each, at the time fixed for the expiration of the contract. This large premium attracted general attention, and people were eager to purchase the Western shares. They rose sensibly during the month of April, 1719, and went nearly to par. Law disclosed his projects; the Regent kept his promise, and authorized him to unite the great commercial companies of the East and West Indies.

The two companies of the East Indies and of China, chartered in 1664 and 1713, had conducted their affairs very badly: they had ceased to carry on any commerce, and had underlet their privileges at a charge which was very burdensome to the trade. The merchants who had bought it of them did not dare to make use of their privileges, for fear that their vessels would be seized by the creditors of the company. Navigation to the East was entirely abandoned, and the necessity of reviving it had become urgent. By a decree of May, 1719, Law caused to be accorded to the West India Company the exclusive right of trading in all seas beyond the Cape of Good Hope. From this time, it had the sole right of traffic with the islands of Madagascar, Bourbon, and France, the coast of Sofola in Africa, the Red Sea, Persia, Mongolia, Siam, China, and Japan. The commerce of Senegal, an acquisition of the company which still carried it on, was added to the others, so that the company had the right of French trade in America, Africa, and Asia. Its title, like its functions, was enlarged; it was no longer called the “West India Company,” but the “Indian Company.” Its regulations remained the same as before. It was authorized to issue another lot of shares, in order to raise the necessary funds either to pay the debts of the companies which it succeeded or for organizing the proper establishments. Fifty thousand of these shares were issued at a par of five hundred francs, which made a nominal capital of twenty-five million. But the company demanded five hundred fifty francs in cash for them, or a total of twenty-seven million two hundred fifty thousand francs, inasmuch as it esteemed its privileges as very great and its popularity certain. It required fifty francs to be paid in advance, and the remaining five hundred in twenty equal monthly payments. In case the payments should not be fully made, the fifty francs paid in advance were forfeited by the subscriber. It was nothing but a bargain made at a premium with the public.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.