Law did then what governments do so often, and always with ill-success: he resorted to forced measures.

Continuing John Law Promotes The Mississippi Bubble,

our selection from The Mississippi Bubble – A Memoir of John Law by Louis Adolphe Thiers published in 1859. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in John Law Promotes The Mississippi Bubble.

Time: 1720

Place: Paris

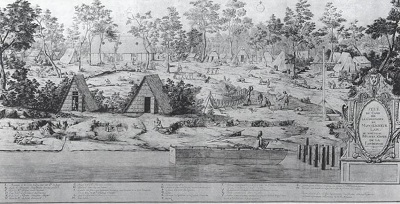

Public domain image from Wikipedia

From this instant, the shares suffered their first decline, and a heavy uneasiness began to spread abroad. The extent of the fall was not measured by those whom it menaced; but people wondered, doubted, and began to be alarmed. The shares declined to fifteen thousand francs. However, the bank-notes were not yet distrusted. The bank was, in fact, entirely distinct from the company, and their fate, up to this time, appeared in no way dependent the one on the other. The notes had not undergone any fictitious and extraordinary advance. Large amounts had been issued, certainly, but for gold and silver, and upon the deposit of shares. The portion which had been issued upon the deposit of shares partook of the danger of the shares themselves; but no one thought of that, and the bank-notes still possessed the entire confidence of the public; only they no longer had the same advantage over specie since the latter had been so much sought by the “realizers.” The notes already began to be presented at the bank for coin, and the vast reserve which it had possessed began to diminish perceptibly.

Law did then what governments do so often, and always with ill-success: he resorted to forced measures. He declared, in the first place, by decree, that the bank-notes should always be worth 5 per cent. more than coin.

In consideration of this superiority in value the prohibition which forbade the deposits of gold and silver for bills, at Paris, was taken off, so that notes could be procured at the bank for coin. This permission was simply ridiculous, for no one now wished to exchange specie for paper, even at par. But this was not all; the decree declared that thereafter silver should not be used in payments of over one hundred francs nor gold in those over three hundred francs. This was forcing the circulation of notes in large payments, and that of specie in small, and was designed to accomplish by violence what could only be expected from the natural success of the bank.

These measures did not bring any more gold and silver to the bank. The necessity of using bank-notes in payment of over three hundred francs gave them a certain forced employment, but did not procure them confidence. Notes were used for large payments, but coin was amassed secretly as a value more real and more assured. The creditors of the state ceased to carry their receipts to the Rue Quincampoix, because they already distrusted the shares; they could not decide to buy real estate, because the price had been quadrupled; they suffered the most painful anxiety, and in their turn embarrassed the holders of shares who needed the receipts to pay their instalments of one-tenth. The catastrophe approached, and nothing could avert it, unless some magic wand could give the company an income of four or five hundred million a year, which was now only seventy or eighty million.

Law, adding measures to measures, at last prohibited the circulation of gold, because this metal was, by its convenience, a rival of bank-notes infinitely more dangerous than silver. He then announced an approaching reduction in the value of coin, which he had raised by a decree in February, only to reduce it again in a short time. The mark, in silver, raised from sixty to eighty francs, was reduced to seventy on April 1st, and sixty-five on May 1st. But this measure was utterly insufficient to bring it to the bank.

The situation grew worse every day; the issue of notes to pay for the shares presented at the bank had risen to two billion six hundred ninety-six million; their depreciation increased; and creditors of every description, being paid in paper which was at a discount of 60 per cent., complained bitterly of the theft authorized by law.

In this juncture, there remained but one step to be taken. As the necessary sacrifice had not been made in the first place, and the shares abandoned to their fate in order to protect the notes, both must now be sacrificed, shares and notes together, in order to finish this wicked fiction. The falsehood of this nominal value, which obliged men to receive at par what was depreciated 30 or 40 per cent., could not be prolonged. The immediate reduction of the nominal value of the shares and bank-notes was the only resource. Sacrifices cannot be too hastily made when they are inevitable.

M. d’Argenson, although dismissed from the treasury, still remained keeper of the seals; he had risen in the esteem of the Regent as Law had declined, and he advised the reduction of the nominal value of the shares and notes as an urgent necessity. Law, who saw in this reduction an avowal of the fiction in the legal values, and a blow which must hasten the fall of the “System,” opposed it with his whole strength. Nevertheless, M. d’Argenson prevailed. On May 21, 1720, a decree, which remains famous in the history of the “System,” advertised the progressive reduction in the value of shares and notes. This reduction was to begin on the very day of the publication of the decree, and to continue from month to month until December 1st. At this last term, the shares were to be estimated at five thousand francs, and a bank-note of ten thousand francs at five thousand; one of a thousand at five hundred, etc. The notes were thus reduced 50 per cent., and the shares only four-ninths per cent. Law, although opposed to the decree, consented to promulgate it.

Scarcely was it published when a fearful clamor was raised on all sides. The reduction was called a bankruptcy; the government was reproached with being the first to throw discredit upon the values which it had created, with having robbed its own creditors, a number of whom had just been paid in bank-notes, even as late as the preceding day — in a word, with assailing the fortunes of all the citizens. The crowd wished to sack Law’s hotel and to tear him in pieces. Nothing that could have happened would have produced a greater clamor; but in times like those it was not only necessary not to fear these clamors: it was even a duty to defy them.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.