Today’s installment concludes John Law Promotes The Mississippi Bubble,

our selection from The Mississippi Bubble – A Memoir of John Law by Louis Adolphe Thiers published in 1859. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of five thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in John Law Promotes The Mississippi Bubble.

Time: 1716

Place: Paris

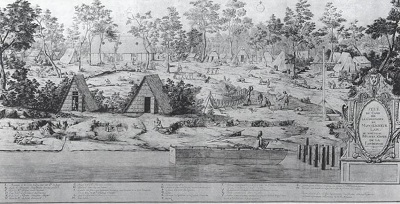

Public domain image from Wikipedia

The reply to the complaints would have soon been evident to the intelligence of everybody. Without doubt the creditors of the state, and some private individuals, who had been paid in bank-notes, were half ruined by the reduction, but this was not the fault of the decree of May 21st — the real reduction was long before this; the decree only stated a loss already experienced, and the notes were worth still less than the decree declared. Because a number of creditors had been ruined by the falsity of nominal values, was it a reason to continue the fiction that it might extend the ruin? On the contrary, it was necessary to put an end to it, to save others from becoming victims. The official declaration of the fact, although it was known before, must produce a shock and hasten the discredit, but it was of little importance that it was hastened, since it was inevitable.

The public thought Law the author of this measure, advised exclusively by M. d’Argenson, and he became the sole object of hatred. The Parliament, making common cause with the public, thought it a good opportunity to take up arms. It did not perceive, in its blind hatred of the “System,” that it was going to render a service to its author, and that to declare itself against the reduction of the bank-notes was to maintain that the values created by Law had a solid foundation. It assembled on May 27th to demand a revocation of the decree of the 21st. At the very moment when it was deliberating, the Regent sent one of his officers to prohibit all discussion, announcing the revocation of the decree.

The Regent had the weakness to yield to the public clamor. Had the decree been bad, its revocation would have been worse. To declare that the shares and notes were still worth what they purported to be availed nothing, for no one believed it, and their credit was not restored by it. A legal falsehood was reaffirmed, and, without rendering any service to those who were already ruined, the ruin of those who were obliged to receive the notes at their nominal value was insured. The decree of May 21st, wise if it had been sustained, became disastrous as soon as it was revoked. Its only effect was to hasten the general discredit, without the essential advantage of reestablishing a real, legal value.

We have just said that the bank was not obliged to pay notes of over one hundred francs. It paid them slowly, and employed all imaginable artifices to avoid the payment of them. Nevertheless, its coffers were almost exhausted, and it was necessary to authorize it to confine its disbursements to the payment of notes of ten francs only. The people rushed to the bank in crowds to realize their notes of ten francs, fearing that these would soon share the fate of those of one hundred. The pressure was so great that three persons were suffocated. The indignant mob, ready for any excess, already menaced the house of Law. He fled to the Palais Royal to seek an asylum near the Regent. The mob followed him, carrying the bodies of the three who had been suffocated. The carriage which had just conveyed him was broken to pieces, and it was feared that even the residence of the Regent would not be respected.

The gates of the court of the Palais Royal had been closed; the Duke of Orléans, with great presence of mind, ordered them to be opened. The crowd rushed into the court and suddenly stopped upon the steps of the palace. Leblanc, the chief of police, advanced to those who bore the corpses, and said, “My friends, go place these bodies in the Morgue, and then return to demand your payment.” These words calmed the tumult; the bodies were carried away and the sedition was quelled.

Severities against the rich “Mississippians” were commenced in this same month of October. For a long time, it had been suspected that the government, following an ancient usage, would deprive them, by means of visas and chambres-ardentes, of what they had acquired by stock-jobbing. A list was made of those known to have speculated in shares. A special commission arbitrarily placed on this list the names of those whom public opinion designated as having enriched themselves by speculation in paper. They were ordered to deposit a certain number of shares at the offices of the company, and to purchase the required number if they had sold their own. The “realizers” were thus brought back by force to the company which they had deserted. Eight days were given to speculators of good faith to make, voluntarily, the prescribed deposit. To prevent flight from the country, it was prohibited, under pain of death, to travel without a passport.

These measures increased still more the decline of the shares. All those whose names were not upon the list of rich speculators, and who could not tell what became of the shares not yet deposited, hastened to dispose of all they retained.

The “System” wholly disappeared in November, 1720, one year after its greatest credit. All the notes were converted into annuities or preferred shares, and all the shares were deposited with the company. Then a general visa was ordered, consisting of an examination of the whole mass of shares, with the purpose of annulling the greater portion of those which belonged to the enriched stock-jobbers.

Law, foreseeing the renewed rage which the visa would excite, determined to leave France. The hatred against him had been so violent since the scene of July 17th that he had not dared to quit the Palais Royal. The following fact will give an idea of the fury excited against him: A hackman, having a quarrel with the coachman of a private carriage, cried out, “There is Law’s carriage!” The crowd rushed upon the carriage, and nearly tore in pieces the coachman and his master before it could be undeceived.

Law demanded passports of the Duke of Orléans, who granted them immediately. The Duke of Bourbon, made rich by the “System,” felt under obligations to Law, and offered money and the carriage of Madame de Prie, his mistress. Law refused the money and accepted the carriage. He repaired to Brussels, taking with him only eight hundred louis. Scarcely was he gone when his property, consisting of lands and shares, was sequestrated.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on John Law Promotes The Mississippi Bubble by Louis Adolphe Thiers from his book The Mississippi Bubble – A Memoir of John Law published in 1859. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on John Law Promotes The Mississippi Bubble here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.