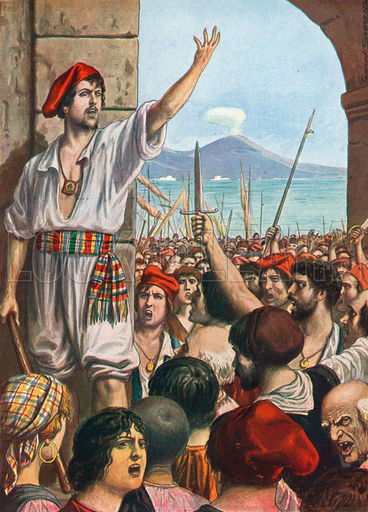

The hand of Masaniello had torn asunder the tie of centuries of habit.

Continuing Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples,

our selection from The Carafa of Maddaloni Naples under Spanish Rule by Alfred Von Reumont published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in twelve easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples.

Time: 1647

Place: Naples

Public domain image from Wikipedia

The bystanders screamed out that this was not what they wanted; he was deceiving them in concert with the Viceroy. In vain he sought to appease them. The tumult increased. Suddenly Masaniello sprang upon the Duke. It was said that he had once received blows instead of gold from one of his servants when he had sold fish at his palace. Perhaps it is only one of the many fables that are attached to the name of the fisherman of Amalfi. Amid wild imprecations he seized the reins of his horse, took hold of the knight by his belt and long hair, tore him from the saddle with the assistance of his followers, and caused his hands to be tightly bound together by a rope; then he delivered the prisoner to Domenico Perrone and his associate Bernardino Grasso, to be strictly guarded.

The last remnant of personal respect for the nobility which the populace had preserved on earlier occasions in the midst of all their disturbances, had now quite disappeared. The hand of Masaniello had torn asunder the tie of centuries of habit. The Viceroy was dreadfully shocked when he knew the danger into which Maddaloni had fallen for his sake. He sent the prior of the Johannites, Fra Gregorio Carafa, brother of the Prince of Roccella, and afterward grand master of Malta to try and obtain the freedom of the Duke. The sensible and placable words of the prior were as useless as his promises: the populace only answered him by screaming for the privileges of Charles V; for the privileges, in gold characters, which Giulio Genuino affirmed that he had seen. Gregorio Carafa felt himself in the same danger as Maddaloni, and returned to the castle without having accomplished anything; but the populace swore that they would allow no parliament which did not deliver up the document.

Masaniello’s prisoner did not remain long in confinement. The man into whose charge he had been committed was under old obligations to him. He conducted him into the convent of the Carmelites and confined him in one of the cells; but when the night came he favored his flight. Diomed Carafa escaped out of the convent in disguise — the fearful tumult and the drunkenness of the people were favorable to him. Unrecognized he gained his liberty; he ascended to the foot of the heights of Capo di Monte, which overlook Naples and its gulf. He wandered to the farmhouse of Chiajano, a considerable distance from the town; here he met a physician who was riding home after visiting a rich man, and he borrowed his horse.

Thus, toward the dawn of day, crossing the streets that were known to him, he reached Cardito, a place on the road leading from the capital to Caserta. Maria Loffredo, to whom the place belonged, received him, and procured him the means of escape from the imminent peril of his life by forwarding him to La Torella in Principato, where the day before the uncle of his wife, Don Giuseppe Caracciolo, had retired with his family. Here the Duke found his wife and children, who, upon the news of his imprisonment, had placed themselves under the protection of their relations. The nobility fled on all sides when they not only saw their property, but even their lives, in danger.

But we must return to Naples, where one event followed another in rapid succession. When the Viceroy saw that the efforts of his messengers proved ineffectual, he resolved to invoke the aid of the Archbishop. He did it unwillingly, for the Spanish rulers never trusted the spiritual superior pastors of Naples, with whom they had perpetual disputes about jurisdiction. Moreover, Cardinal Filomarino endeavored to stand as high in the favor of the people as he was low in that of his fellow-nobles. But the Duke of Arcos had no choice, and so he followed the advice of the papal nuncio, Monsignor Emilio Altieri, afterward Pope Clement X, and sent to the Archbishop to request him to come to the castle.

Asconio Filomarino declared, in the presence of the members of the Collateral Council, that without producing the old document and the ratification of its contents any negotiation was useless, and he would only undertake it under this condition. Then an eager search was instituted, and the charter of privileges was found among the archives of the town in the monastery of San Paolo. Armed with this the Archbishop went to the Carmine, where he was received with rejoicings. The adjacent market was now the head-quarters of the leaders of the people. Here business was transacted, from here orders were issued; here Masaniello, Genuino, and their adherents took counsel together, as did the Duke of Arcos and his faithful followers in the castle. None thought of returning home this fine summer evening.

The Archbishop soon perceived that he had deceived himself in fancying that he could still the waves of this stormy sea. He became conscious that it was not this or that privilege which the tumultuous populace desired; that their minds were chiefly bent upon destruction and murder, and after that upon obtaining quite different rights. While he read to them the old charter, and announced the new concessions of the Viceroy, he perceived how orders were issued and arrangements made that were in direct contradiction to his mission of peace. He saw the mischief spreading rapidly, that every moment was precious, and that the ruin of the city was no spectral illusion. He resolved not to leave the convent that night; indeed, to remain in it until the peace was entirely concluded.

The apprehensions of the prelate were but too well founded. Another fearful evening ensued. The rebellion had gained new strength from the successes of the afternoon. The people had stormed the convent of St. Lorenzo, and thereby got possession of the artillery of the town. Masaniello, with his troops, had made prisoners of war two divisions of troops which the Viceroy wished to gather round him out of Pozzuoli and Torre del Greco. All this only excited men’s minds the more. The proscription-list of the day before did not appear long enough to the people; they desired the destruction of thirty-six palaces of the nobility, and many were consumed by the flames. Houses were burning in the principal streets of the town, and the squares blazed with gigantic piles of furniture, pictures, books, and manuscripts — everything that was found was cast into the flames.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.