At length on Thursday, July 11th, on the fifth day of the insurrection, an agreement was concluded.

Continuing Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples,

our selection from The Carafa of Maddaloni Naples under Spanish Rule by Alfred Von Reumont published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in twelve easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples.

Time: July 11, 1647

Place: Naples

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Many shots were fired behind him, none hit him. Things went on wildly in the market-place. From two to three hundred banditti attacked the populace, who quickly recovered themselves and easily defeated the assailants. The most horrible carnage followed. “The people,” relates Filomarino, “thronged with great violence to the convent, in the belief that there banditti or their adherents were concealed. They ransacked everything, but found nothing excepting six barrels of powder. Your holiness may imagine the state of indescribable confusion of the town, while thirty thousand armed men, breathing rage and vengeance, rushed about, murdering all suspicious persons. The worst part went on in the church and convent of the Carmine, where I was staying. In my room I gave many dying persons the absolution; among them a tailor, who was shot down at my side.

“When the carnage came to an end it was suddenly rumored that the banditti had poisoned the springs at Poggio Reale, which supply the greater part of the town with water. The fury of the people was again roused. I caused a pitcher of water to be brought, and drank it in the presence of many persons, which silenced the suspicion; and as your holiness is much respected in this town, and even from the time in which you were a nuncio here, they have a pleasant recollection of you, so in the time of utmost need I bless the people in your name, and admonish them to be quiet for the love of you, which also does not fail of its effect.”

The Viceroy was so much the further from coming to any agreement, the more Masaniello’s power and authority increased and the more uncomfortable and dangerous the position of the Viceroy became, in the midst of a rebellious city, in the confined space in the castle, and a scarcity of provisions. He therefore thought himself obliged to discover in writing a knowledge of the unsuccessful plan of Diomed Carafa, and pressed the Archbishop to hasten the business. This was not easy, owing to the savage excitement of the victorious and drunken populace, and the intrigues of the artful advisers of the Fisherman, who were pursuing, at the same time, their own selfish aims.

The streets were become to such a degree the theatre for deeds of violence that Masaniello issued an order that each person was obliged to keep a lamp or torch burning before his own dwelling. The assaults made with daggers, pocket pistols, and other short weapons were so frequent that, after the leader of the people had been twice shot at, a prohibition was issued against wearing cloaks and long clothes that could conceal such weapons. Even women were no longer allowed to wear certain articles of clothing, which on account of their size were called guard infante, and even Cardinals Filomarino and Trivulzio laid aside their robes.

In the most important positions of the city barricades were built with baskets full of earth and heavy planks for the double purpose of repelling the sallies of the Spaniards from the castle, and preventing them from receiving supplies from without. The people were masters of the whole town, with the exception of Castelnuovo, the park, and the adjoining artillery, and of the castles dell’ Uovo, Sant’ Elmo, and Pizzofalcone, positions which placed it in the power of the Spaniards to turn Naples into a heap of ruins if they made use of the artillery. But the Duke of Arcos wished to spare the town as long as possible, and the castles were weakly garrisoned, and still less stocked with provisions.

At length on Thursday, July 11th, on the fifth day of the insurrection, an agreement was concluded.

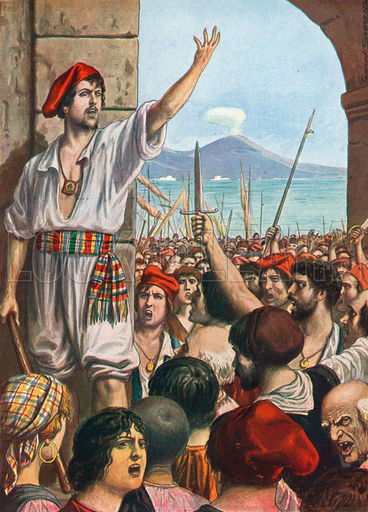

In the church of the Carmelites it was solemnly announced that the Viceroy had formally confirmed the old privileges of the town, and increased them by new ones, which were immediately made known. As a proof and seal of the reconciliation, Masaniello, who had now, besides the power, the title also, of a captain-general of the most faithful people, was to have a conference with the Viceroy. It was difficult to persuade the Fisherman to take this step. He owned that he saw the gallows before him; he would confess thoroughly before he went, and it required all the Archbishop’s power of persuasion to decide him.

At last he consented, under the condition that the conference should be in the palace, and not in the castle. He previously issued a proclamation through the whole town to know how many armed men could be marched out. The answer was a hundred forty thousand, but three hundred thousand if there were arms ready for them. A number of men indeed poured forth from the environs, but it is easy to perceive the exaggeration of the numbers. When everything was arranged, Masaniello began to dress himself; he had fasted the whole day, excepting some white bread dipped in wine after the cardinal’s physician had tasted it, for he was possessed with the idea of being poisoned, and almost starved himself. His dress was of silver brocade; he wore at his side a richly ornamented sword; his head was covered with a hat with a white plume in it.

In such pomp he is represented in a remarkable picture by the hand of Domenico Garguilo — called Micco Spadone — whose paintings have represented to us many of the scenes of this revolution. The Fisherman of Amalfi is riding at the head of a tumultuous crowd, surrounded by adults and boys; his white horse is made to gallop; upon his breast is to be seen a medallion with a picture of the Madonna of Carmel. In the middle of the market-place, where the scene opens opposite to the church of the Carmelites, there are bloody heads ranged in a double row round a marble pedestal on which no statue is any longer to be seen, and the gibbet and the wheel await the new victims among those who are persecuted, or have already been dragged thither by the populace.

The afternoon was already advanced when Cardinal Filomarino got into his carriage, before the church, with his house-steward, Giulio Genuino, and two persons of his suite. Masaniello rode at his right hand, and at his left Arpaja, the deputy of the people. In the streets through which the procession passed, from the market-place to the square of the castle, the people were armed, and formed into bands of six thousand companies, who lowered their colors before the cardinal and the captain-general.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.