Today’s installment concludes Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples,

our selection from The Carafa of Maddaloni Naples under Spanish Rule by Alfred Von Reumont published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of twelve thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples.

Time: 1647

Place: Naples

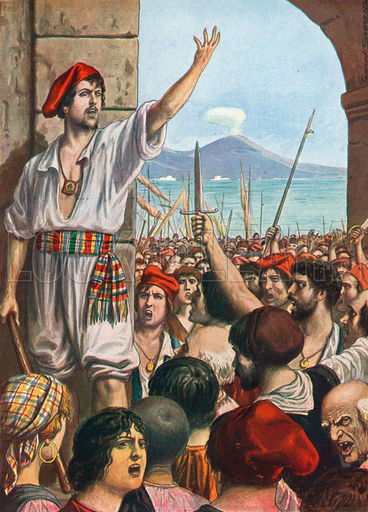

Public domain image from Wikipedia

During the night all the military posts were strengthened, soldiers were concealed in different houses, and the galleys were brought near the shore. Silently and gloomily the masses filled the streets; a dull mood seemed to have taken possession of everyone. The Archbishop was celebrating high mass in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine. Scarcely was it ended and the prelate gone when Masaniello, with a crucifix in his hand, mounted the pulpit. His speech was a mixture of truth and madness; he complained of the inconstancy of the people, enumerated his services, described the oppressions that would fall upon them if they deserted him; he confessed his sins, and admonished the others to do the same before the Holy Virgin, that they might obtain the mercy of God, and as he raised the crucifix to bless the people a woman called to him to be silent, that the Mother of God would not listen to such nonsense. He began to undress himself in the pulpit, to show how emaciated he was by labor and sleepless nights. A Carmelite monk then sprang upon the lunatic, compelled him to descend the steps, and dragged him, with the assistance of the rest of the monks, into the convent, where, in a complete state of exhaustion, he flung himself upon a bed in one of the cells and fell asleep.

The mercenaries hired by the Duke of Arcos and nine men belonging to the people had been for a long while in the church, armed with daggers and pistols. Scarcely was the divine service ended, which had been interrupted by this scandalous scene, when these men hastened to the convent and inquired for Masaniello. The monks wanted to defend him; an uproar took place. The sleeper awoke, believed that they were some of his followers, and hastened to the gates. At the same moment the murderers pressed into the passage and perceived their victim. Five shots were fired. Mortally wounded by one of them, he fell to the ground, while he covered his face with his hand, uttering the cry, “Ah, ye vagabonds!”

Salvatore Cattaneo cut off his head with a blunt knife, seized hold of it by the hair, and hastened out with the cry, “Long life to the King of Spain!” The populace stood there thunderstruck; no sound was heard, but none detained the murderers, who hurried off. They soon met some small bands of Spanish soldiers, whom they joined, and exclaiming “Long life to Spain!” they went on. The Viceroy, accompanied by numerous noblemen, had just left the castle to go into the park when the news of the accomplishment of the deed reached him. It is said that he showed his joy in a way unbecoming his high rank; but Don Francesco Capecelatro, who was present, only remarks that the news arrived at the moment that the Duke of Arcos had said he would pay ten thousand ducats to any person who would bring him Masaniello dead or alive.

The tumult began immediately afterward. The murderers came, bearing the head upon a pike; boys seized the corpse, dragged it through the streets, and buried it outside the city walls by the gate which leads to the market-place. Many best known as partisans of the murdered man atoned by their lives for their short day of power. His relations were secured. But still the humor of the people was so little to be trusted that the Viceroy caused the fortifications to be hastily put in repair.

The news of the deed reached Cardinal Filomarino while on his way from the Carmine to his own house; he went directly to the palace, and then rode with the Duke of Arcos and many of the principal nobles to the cathedral, and from thence through the streets to the market. The armed troops of people still stood everywhere; they lowered their colors with the cry, “Long life to the King and the Duke of Arcos!” The privileges were confirmed and a general pardon proclaimed, from which only Masaniello’s brother and brother-in-law were excluded.

Francesco Antonio continued to be deputy of the people; Giulio Genuino entered upon his promised office as one of the presidents of the chamber; on the very same day many of the nobles returned to their deserted mansions.

The populace was still as if stunned; but as soon as the following morning, when the price of bread was raised because the commissary-general of provisions and the bakers declared that it was quite impossible to subsist upon the hitherto low prices, the humor of the people suddenly changed. The mob complained that its hero and deliverer had been given up; they hastened to dig up the corpse; they sewed the head to the body, washed it, put on it some sumptuous clothes, and laid it with his bare sword and staff of command upon a bier covered with white silk; which was borne by the captains Masaniello had appointed. About four thousand priests conducted the procession by the order of the Archbishop, who wavered incessantly between the two parties, and excited more evil than good. The standard-bearers dragged their banners upon the ground, the soldiers lowered their arms, the dull sound of muffled drums was heard. Above forty thousand men and women followed the coffin, some singing litanies, the others telling their beads. The bells pealed from all the steeples, lights were burning in all the windows. The procession had left the Carmine at the twenty-second hour of the day; it did not return till the third hour of the night. The corpse was lowered into the earth with the usual ceremonies in the vicinity of the church doors.

Never had a viceroy or a great prince been borne to the grave as was Tomaso Aniello of Amalfi.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples by Alfred Von Reumont from his book The Carafa of Maddaloni Naples under Spanish Rule published in 1851. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.