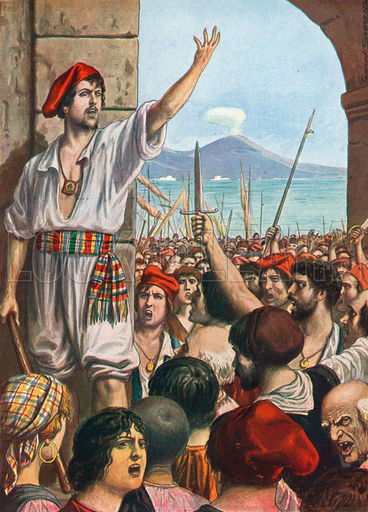

Masaniello now placed himself at the head of this troop of people, and marched with them in procession through the town.

Continuing Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples,

our selection from The Carafa of Maddaloni Naples under Spanish Rule by Alfred Von Reumont published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in twelve easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples.

Time: 1647

Place: Naples

Public domain image from Wikipedia

The mothers ran to and fro with their children, whose little hands dragged after them what they could. As if around charcoal piles the charcoal-burners, those half-naked, half-savage inhabitants of the caves and alleys of the poisonous quarters of the poor in Naples, hovered with a fearful activity about these holocausts to the fury of the people, in perpetual motion and with unceasing cries and howlings. The entrances to the principal streets were secured by artillery; the bells were ringing incessantly, during which they carried about in procession effigies of Philip IV, proclaiming, “Long life to the King of Spain!” and planted the royal banner to wave together with that of the people, upon the lofty steeple of San Lorenzo.

In this manner passed the night. Cardinal Filomarino remained in the convent of the Carmelites in active negotiation with the heads of the people. Many were the difficulties. The insurgents went as far as to demand that the castle of St. Elmo should be delivered up to them, and a wild storm burst out when the words of pardon and rebellion were mentioned in the concessions of the Viceroy. “We are no rebels!” they roared confusedly; “we want and need no pardon.”

The Archbishop was exhausted when the morning came and still no result. As the former day had ended in fire and desolation, so the present one — it was Wednesday, July 10th — commenced with desolation and fire. The news of Maddaloni’s flight was like pouring oil upon the flames. If he had escaped, his effects should atone for it. Already the day before they had wanted to set fire to his palace, as well as those of many of the Carafas, that of Don Giuseppe, of the Prince and of the prior of Roccella, of the Prince of Stigliano, and others belonging to the family.

Now a dense multitude moved toward the Borgo de’ Vergini, where, by the Church of Santa Maria della Stella, without the then city walls, Diomed Carafa resided. But the affair turned out differently from what they had expected. Armed servants occupied the house, numerous arquebuses glittered from the windows; and the people from the market and from Lavinaro, who knew Masaniello’s bravos only too well, contented themselves for the present with smashing some of the panes of glass, by flinging stones, and reserved their vengeance for a better opportunity, which did not fail them.

Masaniello had meanwhile, with a presence of mind and a dexterity to which our admiration cannot be denied, profited by the time to extend and strengthen the authority so rapidly acquired over his contemporaries and superiors. He held counsel and issued decrees with his associates — with Genuino, who continued the soul of the insurrection; with the new deputy of the citizens, Francesco Antonio Arpajo, Genuino’s old accomplice in his intrigues — and some insignificant persons. If during the first three days everything had been done in wild confusion, now the insurrection was formally organized.

The people were informed that they were to assemble according to their quarters in the town, and meet in the market-place. The companies were formed immediately; more than one of them consisted of women belonging to the lowest class. It may be imagined what a band they formed when we consider the horrid race of women belonging to this class at Naples, in which corrupt blood struggles for preëminence with dirt and rags.

Masaniello now placed himself at the head of this troop of people, and marched with them in procession through the town. They were one hundred fourteen thousand in number, most of them provided with fire-arms; for all the shops and magazines for arms, as well as the houses of the nobility, had been ransacked. Those among the citizens who would not march with them were obliged to stand armed before their own dwellings at the command of a fisherman, and in the name “of the most faithful people of the most faithful town of Naples, and in those who, by the grace of God and our Lord Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary, hold in their hands the government of the same.”

Oppressive decrees were issued; on one side were the royal arms, and on the other those of the people. “This Masaniello,” writes Cardinal Filomarino, “has risen in a few days to such a height of authority and influence, and has known how to acquire so much respect and obedience, that he makes the whole town tremble by his decrees, which are executed by his followers with all punctuality and obedience. He shows discretion, wisdom, and moderation; in short, he has become a king in this town, and the most glorious and triumphant in the world. He who has not seen him cannot imagine him; and he who has cannot describe him exactly to others. All his clothing consists of a shirt and stockings of white linen, such as the fishermen are accustomed to wear; moreover, he walks about barefooted and with his head uncovered. His confidence in me and respect for me are a real miracle of God’s, whereby alone the attainment of an end or understanding in these perplexing events is possible.”

How the pious Archbishop deceived himself in thinking that he had obtained his aim! Still he subdued the first storm which interrupted the negotiation, but the following one neither he nor anyone else could get the mastery over. He had been to Castelnuovo to obtain from the Viceroy the ratification of the conditions stipulated for by the leaders of the people, and was on the point of concluding the agreement in the Carmelite monastery when in an instant the most dreadful tumult began. Domenico Perrone, who had remained near Masaniello, had showed himself but little since the flight of the Duke of Maddaloni, because the suspicion was abroad that he had favored his escape. The church was full of men, who prevented the termination of the conferences, when this Perrone stepped up to the Fisherman and took his place by his side, as if he had something to tell him. At this moment a shot was fired; Masaniello hastened to the gates and cried out, “Treason!”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.