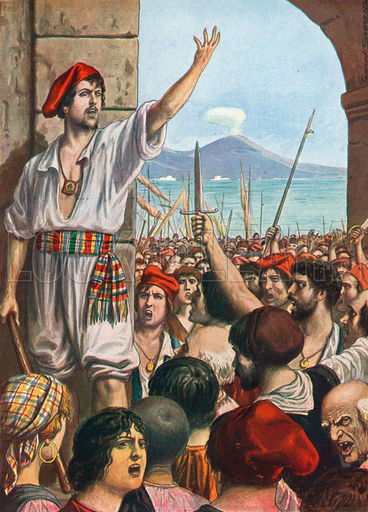

The power of the Fisherman of Amalfi was at its height; but already he was near his ruin.

Continuing Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples,

our selection from The Carafa of Maddaloni Naples under Spanish Rule by Alfred Von Reumont published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in twelve easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples.

Time: 1647

Place: Naples

Public domain image from Wikipedia

During the reading of these articles Masaniello had been very uneasy, and had made observations first on one point and then on another. When Donato Cappola had finished reading he wanted to take off his sumptuous dress of silver brocade in the middle of the church, because he declared that he was now nobody. When he was hindered from doing this, he flung himself upon the ground and kissed the feet of the cardinal. The Duke of Arcos swore to the contract, with his hand upon the Gospels. The Archbishop sang the Te Deum, and the people shouted “Long life to the King of Spain!” The companies fired their rifles; the Viceroy returned through the streets, swarming with men, to the castle, and everywhere resounded the cry, “Long life to the King and the Duke of Arcos!” Then, as Masaniello returned home, the companies all lowered their colors as he passed.

The power of the Fisherman of Amalfi was at its height; but already he was near his ruin. The unusual way of life, the always increasing excitement, the constant speaking and watching, the small quantity of nourishment which he took from dread of poison — all this, in the most fearful heat of summer, affected him bodily and completely turned his head. His actions can only be explained by their being the beginning of insanity. If a crowd of people did not please him, he attacked and wounded them right and left. All the persons, amounting to a thousand, that lived near his cottage on the market-place he expelled from their dwellings, that these might be destroyed and he might build a large palace for himself. He lavished gold and silver with prodigality, and gave a number of prostitutes rich dowries; he distributed the titles of princes and dukes, gave great banquets at Poggio Reale and at Posilipo, to which he invited the Viceroy, and sent his wife and mother in magnificent dresses to visit the Duchess of Arcos. “If your excellency is the vice-queen of the ladies,” said the Fisherman’s wife, “I am the vice-queen of the women of the people.”

But fear of the Duke of Maddaloni haunted him like a specter. He ordered his beautiful villa at Posilipo to be destroyed, and made his people ransack once more his pillaged palace at Santa Maria della Stella. The barber of the Duke and a Moorish slave bought their lives, the first by giving him various jewels that had been concealed, and the other told him that it was Diomed Carafa who had caused the admiral’s ship to be set on fire, which had been blown into the air the preceding May. The Moor, for this lie, obtained the command of four companies of the people. The Fisherman put to death many poor musicians merely because they had been in the service of Maddaloni. The Duke’s correspondence was intercepted, but as it was written in cipher it only increased the suspicion. The new master of Naples repaired himself to the palace of Carafa, and wanted to dine there; but he changed his mind, and had a dinner served up with great pomp at a neighboring convent.

While he was eating there, some of his people dragged thither two portraits of the Duke and his father, Don Marzio. Upon them he vented his childish rage; smashed the frames; cut out the heads, which he put on pikes, which he commanded to be placed on the table before him. On his return from the market he put on a suit of Carafa’s clothes, of blue silk embroidered with silver; he hung on his neck a gold chain, and fastened in his hat a diamond clasp, all the property of his enemy who had escaped. Then he flung himself on a horse, drew forth his pistols with both hands, and threatened to shoot anyone who approached him, or who showed himself at the windows, galloped to the sea, where was the gondola of the Viceroy, undressed himself in it, was dried with fine Dutch linen, and put on a shirt of Maddaloni’s trimmed with lace; and hearing that Maddaloni had gone toward Piedimonte d’Alife, he ordered a troop of two thousand men to march thither and seize him. But as these men, undisciplined in arms, as usual played their parts as heroes better in the streets than in the open field, they fared wretchedly.

The Prince of Colobrano, a cousin of the Duke’s, with some other friends, surprised them suddenly in the mountains with not more than a hundred men. Many perished in battle, others of their exertions and hunger, and, when the intelligence of Masaniello’s unfortunate end reached them, the wretched remainder of the troops returned to Naples.

Masaniello’s supremacy was approaching its termination — madness and cruelty strove within him. It was the worst kind of mob rule. At the entrance of the Toledo, not far from the royal palace, a high gallows was erected. Every complaint was listened to, and no defense; no one felt secure in his home or in his family; the houses of the nobility all stood empty, and the most sensible of the people saw that the continuation of this state of things could only lead to universal ruin; the churches were profaned under the pretext that treasure or banditti were concealed in them; the terrible decorations of the great market-place were increased by above two hundred heads, and spread a real plague under the scorching rays of the sun. Cardinal Filomarino had either lost his influence or else the dread of losing his popularity made him impotent. Yet he wrote to the Pope: “The wisdom, the acuteness, and the moderation first shown by this man are entirely gone since the signature of the capitulation, and are changed into audacity, rage, and tyranny, so that even the people, his followers, hate him.”

Among these followers, before all, were Genuino and Arpajo; but when they saw that they could do nothing with this hare-brained man, that everything was going to ruin, and that their own ill-acquired position was therefore in the greatest danger, they came to an understanding with the Viceroy and his Collateral Council. The Viceroy, in his own person, conferred with common murderers, and the Feast of Our Lady of Carmel, on Thursday, July 16th, was fixed for the execution of the plan.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.