The articles of the treaty were confirmed, and their publication was to take place two days afterward.

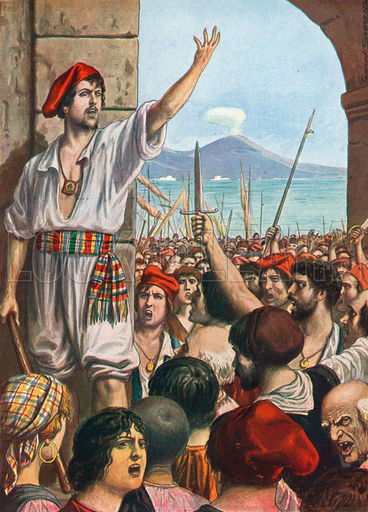

Continuing Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples,

our selection from The Carafa of Maddaloni Naples under Spanish Rule by Alfred Von Reumont published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in twelve easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples.

Time: 1647

Place: Naples

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Thousands and thousands had hastened thither to witness so remarkable a spectacle. In the square of the castle were placed over the gate of the palace of the Prince of Cellamare the effigies of Charles V and Philip IV under a canopy. Masaniello stopped, drew out the charter of the old privileges, together with the new, that he carried before him on his saddle, and spoke to the assembled crowd, to whom he announced that everything was settled. The people replied that what he had done was well done, and so the procession marched on, preceded by a trumpeter, proclaiming, “Long life to the King, and the most faithful people of Naples!”

The Viceroy had repaired to the palace, which had been hastily prepared. He received the deputation of the people in the saloon of Alva, where the frescoes recalled the most glorious times of Spain.

Masaniello flung himself down before him; the Viceroy raised him up, with friendly words, embraced him, went with him and the cardinal into the adjoining royal saloon, and when the throng of people filled the square and the uproar continued to increase, he entreated him to show himself on the balcony. Masaniello did it; but when he reentered the saloon he was so overpowered by the sensations of the day that he sank unconscious on the ground. Now the Viceroy became uneasy when he thought of the vengeance of the people if anything happened to their idol. But Masaniello recovered, and the actual conference began.

The articles of the treaty were confirmed, and their publication was to take place two days afterward. Masaniello was recognized in his office as captain-general of the people, received a golden chain, and was conducted by the proud Duke to the stairs, and publicly called a faithful servant of the King and a glorious defender of the people. He kissed the hand of the Viceroy, and was dismissed by him with another embrace.

The peace was concluded, though not yet solemnly ratified; but how little did the state of the town correspond to it! In the same night, while Masaniello was entertained by Cardinal Filomarino, a cry was again raised of treason and banditti; watch-fires were kindled, and the clatter of arms heard. The captain-general of the people governed, as there was no magistrate in Naples. In the obscurity of the night he caused the heads of fourteen persons to be cut off, without trial or judgment, upon the accusation of their being banditti. He had a wooden scaffold erected before his house of the same sort as the booths of the mountebanks. Here he issued his orders, and printed decrees appeared: “By the command of the illustrious Lord, Maso Aniello of Amalfi, Captain-general of the Most Faithful People.” He had memorials and petitions brought to him on the point of a halberd, and read to him by his secretary, upon which he issued his orders like an absolute ruler.

The price of oil and of corn was fixed. It was forbidden to show one’s self in the streets after the second hour in the night, excepting to minister the last rites of the Church, or to visit the sick and women in labor. All priests were to present themselves, that it might be investigated whether they were real ecclesiastics or banditti in disguise. A number of burdensome directions about costume were published. There was a rich harvest for spies and accusers.

What had been at the first a defense against tyranny and arbitrariness became now only worse tyranny. No families of noble rank could remain. None could trust or even order about their servants, for Masaniello summoned the domestics to arms and rewarded their treachery to their lords. Armed bands, under known leaders, had formed themselves, and went their own ways unchecked. Five days were sufficient to put an end to all discipline and order. During these wild doings no privacy could be had. If the errors of the nobility had been borne hitherto, now began the saturnalia of the populace, and they were far more bloody and horrible than those of the nobles.

This was the condition of the town of Naples at the time when King Philip’s Viceroy and the Captain-general of the Most Faithful People met in the cathedral on July 17th to publish solemnly the new treaty. The venerable church had witnessed many changes in the relations and destinies of the kingdom proclaimed in her vaulted halls, with the history of which it had, so to speak, grown up; but never had it been the theatre for such a degradation of the royal power.

Before the ceremony took place, the Duke of Arcos was obliged to submit to many humiliations. No cavalier was allowed to accompany him in the procession, because Masaniello had forbidden it. The Fisherman had disarmed all persons of rank, but armed popolans stood in double rows along the streets, which were necessarily cleansed from dirt and rubbish, and the balconies were hung with tapestry. The Cardinal-archbishop, in pontifical attire, took his seat under the baldachin, while at some distance from him sat the Viceroy and Masaniello. The Knight of Alcantara, Donato Cappola, Duke of Canzano, read the articles instead of the secretary of the kingdom. The principal contents were the confirmation of the old privileges of Ferdinand of Aragon till the time of Charles V; a remission of all guilt and punishment for crimes of lese-majesté, and, on account of the disturbances, an equality of the nobility and the people with reference to the number of votes in affairs of the town; the abolition of all gabelles and taxes which had been introduced since the time of the emperor Charles V, with the exception of those upon which private persons had rights; liberty of the market, and remission of punishment for the excesses committed in the destruction of houses and property. The ratification of the treaty from Madrid was to follow within the three months; till that time the people were to continue in arms.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.