The Prince of Montesarchio was the first whom the Viceroy sent as a messenger of peace.

Continuing Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples,

our selection from The Carafa of Maddaloni Naples under Spanish Rule by Alfred Von Reumont published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in twelve easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples.

Time: 1647

Place: Naples

Public domain image from Wikipedia

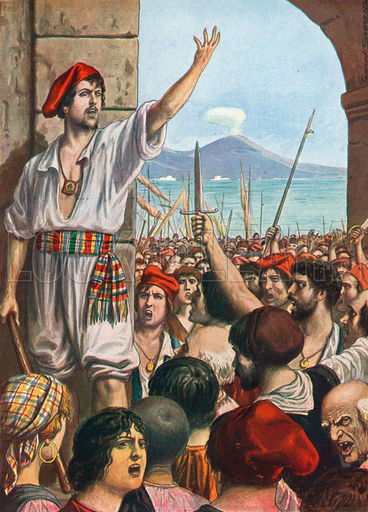

Hitherto but few, comparatively, of the rebels had been armed; they felt this deficiency and wanted to procure themselves arms and artillery. With this view they attacked the convent and belfry of San Lorenzo, but the small Spanish garrison received them with sharp firing, and they were obliged to retire; they only committed the more acts of wanton cruelty. The most fearful confusion prevailed; first in one place and then in another the sky was red with the conflagration. Suddenly a lurid light illumined the towers and projecting buildings. The market-place was the principal quarter of the insurgents, who still wanted a leader. There, toward midnight, four men, masked, wearing the habit of one of the holy brotherhoods, entered a circle of men composed of the dregs of the populace — among them was Masaniello. Giulio Genuino, one of the four men, took off his mask. He had excited and fanned the flame the whole day, and now he sought, in the darkness of the night, to complete what he had begun.

They had done right, he said, to let the King of Spain live, for it was not a question of taking the crown of Spain off his head, but to put an end to the oppression of the people by his covetous ministers. They must not rest till they had obtained this; but to obtain it, it was necessary above all things to procure themselves arms, and, by the choice of a leader, to give union and steadiness to their undertaking. They all agreed with him, and that very same night they followed his advice and provided themselves with arms. They stormed the shops of the sword-cutlers, and took possession of five pieces of light artillery belonging to the proprietor of a ship, and even during this first night the name of Masaniello passed from mouth to mouth.

The morning came, but it brought neither assistance nor repose. When the day dawned there was a beating of drums, a ringing of bells, and country people pouring in from all sides. The discontented vassals of the barons in the neighborhood, the banditti, and vagabonds of all kinds increased the masses of the populace of the capital, who were augmented by troops of horrible women, and children more than half naked, making the most dreadful uproar. Arms of all kinds were in the hands of the insurgents; some of them made use of household and agricultural implements both for attack and defense. Unfortunately, various powder-magazines fell into their hands.

At Little Molo they stormed a house in which ammunition had been placed; it caught fire and blew up; about forty persons were killed and double the number wounded, most of them severely. The exasperation only increased. It was soon observed that it was not blind fury alone which conducted the rebellion — clever management was evident. The Count of Monterey had given the people a sort of military constitution, as he divided them into companies according to the quarters of the town, which resembled those Hermandades which the Archbishop of Tortosa, afterward Pope Adrian VI, formed in the time of Charles V in Spain, and that afterward caused an insurrection of the Communeros. This practice in the forms of war was now of use to the insurgents, and when on the second morning some of the working classes and mechanics, and persons indeed that belonged to a higher class of citizens, joined themselves to the actual mob, thinking to obtain a better government in consequence of the insurrection, the danger increased. The two principal leaders were Domenico Perrone, formerly a captain of sbirri, and Masaniello, whom the people about the market-place and the Lavinaro and its vicinity had chosen: but Giulio Genuino conducted the whole affair by his counsel.

A formal council of war was held in Castelnuovo. The Viceroy was quite aware that the utmost he could do with his few troops would be to defend these fortresses of the town against the people, but that he could not subdue them. He was, moreover, reluctant to make use of fire-arms, as the insurgents proclaimed aloud everywhere their loyalty to the King. So he resolved to open a negotiation, to regain his lost ground, or at least to gain time.

The Duke of Arcos has been accused of having, even in these early moments, conceived the plan to push the nobles forward, with the view to make them more hateful than ever to the populace, and thus to annihilate their influence completely, a policy that was so much the more knavish the more faithfully the nobles had stood by him during these last eventful twenty-four hours, at the peril of their own lives. Whatever his plan may have been, the result was the same; whether the idea proceeded from the Duke of Arcos, or his successor, the Count of Onate, the insurrection of 1647 caused the ruin of the aristocracy.

The Prince of Montesarchio was the first whom the Viceroy sent as a messenger of peace. The name of D’Avalos was through Pescara and Del Vasto closely associated with the warlike fame of the times of Charles V. His reputation had been brilliant from the period of the Moorish wars until now. Great possessions secured him great influence in many parts of the kingdom. Montesarchio rode to the market-place provided with a written promise of the Viceroy’s touching the abolition of the taxes. He took an oath in the church of the Carmelites that the promise should be kept; the people refused to believe him. Then the Duke of Arcos resolved upon sending others. The general of the Franciscans, Fra Giovanni Mistanza, who was in the castle, directed his attention to the Duke of Maddaloni.

Diomed Carafa had been for some time again a prisoner in Castelnuovo. Transactions with the banditti and arbitrary conduct toward the people had brought him to captivity, which was shared by his brother Don Giuseppe. For what reason he was selected for this work of peace, who had so heavily oppressed the lower classes, and had committed such acts of violence that he had the credit of being the leader of the most licentious cavaliers, is uncertain. It was said to be because he, as a patrician of the Seggio del Nido, had most counteracted the mischief of the tax, and therefore the populace was better inclined toward him than the members of the other sedeles.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.