Today’s installment concludes Neptune Discovered,

our selection from Pioneers of Science by Sir Oliver Lodge published in 1893. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of three thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Neptune Discovered.

Time: 1846

Place: (disputed)

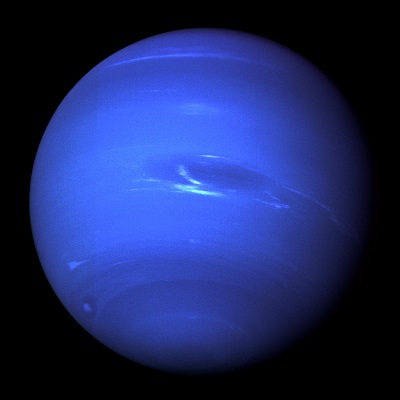

Public domain image from NASA

Not without failures and disheartening complications was this part of the process completed. This was, after all, the real tug of war. Many unknown quantities existed: its mass, its distance, its eccentricity, the obliquity of its orbit, its position–nothing was known, in fact, about the planet except the microscopic disturbance it caused in Uranus, several thousand million miles away from it. Without going into further detail, suffice it to say that in June, 1846, he published his last paper, and in it announced to the world his theory as to the situation of the planet.

Professor Airy received a copy of this paper before the end of the month, and was astonished to find that Leverrier’s theoretical place for the planet was within 1° of the place Adams had assigned to it eight months before. So striking a coincidence seemed sufficient to justify a Herschelian sweep for a week or two. But a sweep for so distant a planet would be no easy matter. When seen through a large telescope it would still only look like a star, and it would require considerable labor and watching to sift it out from the other stars surrounding it. We know that Uranus had been seen twenty times, and thought to be a star, before its true nature was discovered by Herschel; and Uranus is only about half as far away as Neptune.

Neither at Paris nor at Greenwich was any optical search undertaken; but Professor Airy wrote to ask M. Leverrier the same old question that he had fruitlessly put to Adams: Did the new theory explain the errors of the radius vector or not? The reply of Leverrier was both prompt and satisfactory–these errors were explained, as well as all the others. The existence of the object was then for the first time officially believed in. The British Association met that year at Southampton, and Sir John Herschel was one of its sectional presidents. In his inaugural address, on September 10, 1846, he called attention to the researches of Leverrier and Adams in these memorable words:

“The past year has given to us the new [minor] planet Astraea; it has done more — it has given us the probable prospect of another. We see it as Columbus saw America from the shores of Spain. Its movements have been felt trembling along the far-reaching line of our analysis with a certainty hardly inferior to ocular demonstration.”

It was nearly time to begin to look for it. So the astronomer-royal thought on reading Leverrier’s paper. But as the national telescope at Greenwich was otherwise occupied, he wrote to Professor Challis, at Cambridge, to know whether he would permit a search to be made for it with the Northumberland equatorial, the large telescope at Cambridge University, presented to it by one of the Dukes of Northumberland.

Professor Challis said he would conduct the search himself, and shortly began a leisurely and dignified series of sweeps around the place designated by theory, cataloguing all the stars he observed, intending afterward to sort out his observations, compare one with another, and find out whether any one star had changed its position; because if it had it must be the planet. Thus, without giving an excessive time to the business, he accumulated a host of observations.

Professor Challis thus actually saw the planet twice — on August 4 and August 12, 1846 — without knowing it. If he had had a map of the heavens containing telescopic stars down to the tenth magnitude, and if he had compared his observations with this map as they were made, the process would have been easy and the discovery quick. But he had no such map. Nevertheless one was in existence. It had just been completed in that country of enlightened method and industry–Germany. Doctor Bremiker had not indeed completed his great work–a chart of the whole zodiac down to stars of the tenth magnitude–but portions of it were completed, and the special region where the new planet was expected to appear happened to be among the portions finished. But in England this was not known.

Meanwhile Adams wrote to the astronomer-royal several additional communications, making improvements in his theory, and giving what he considered nearer and nearer approximations for the place of the planet. He also now answered quite satisfactorily, but too late, the question about the radius vector sent to him months before.

Leverrier was likewise engaged in improving this theory and in considering how best the optical search could be conducted. Actuated probably by the knowledge that in such matters as cataloguing and mapping Germany was then, as now, far ahead of all the other nations, he wrote in September (the same year that Sir John Herschel delivered his eloquent address at Southampton) to Berlin. Leverrier wrote to Doctor Galle, head of the observatory at Berlin, saying to him, clearly and decidedly, that the new planet was now in or close to such and such a position, and that if he would point his telescope to that part of the heavens he would see it; and moreover that he would be able to tell it from a star by its having a sensible magnitude, or disk, instead of being a mere point.

Galle got the letter on September 23, 1846. That same evening he pointed his telescope to the place Leverrier told him, and saw the planet. He recognized it first by its appearance. To his practised eye it did seem to have a small disk, and not quite the same aspect as an ordinary star. He then consulted Bremiker’s great star-chart, the part just engraved and finished, and, sure enough, no such star was there. Undoubtedly it was the planet.

The news flashed over Europe at the maximum speed with which news could travel at that date (which was not very fast); and by October 1st Professor Challis and Mr. Adams heard it at Cambridge, and realized that in so far as there was competition in such a matter England was out of the race.

It was an unconscious race to all concerned, however. The French scientists knew nothing of the search in England. Adams’s papers had never been published; and very annoyed the French were when a claim was set up in his behalf to a share in this magnificent discovery. As for Adams himself, we are told that by no word did he show resentment at the loss of the practical consummation of his discovery. His part in any controversy that arose was calm and dignified; but for a time his friends fought a public battle for his fame. It so happened that the public took a keener interest than it usually takes in scientific predictions; but the discussion has now settled down. All the world honors the bright genius and mathematical skill of John Couch Adams, and recognizes that he first solved the problem by calculation. All the world, too, perceives clearly the no less eminent mathematical talents of M. Leverrier, but it recognizes in him something more than the mere mathematician–the man of energy, decision, and character.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Neptune Discovered by Sir Oliver Lodge from his book Pioneers of Science published in 1893. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Neptune Discovered here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.