But anyone in the situation of the astronomer-royal knows that almost every post brings absurd letters from ambitious correspondents, some of them having just discovered perpetual motion, or squared the circle, or proved the earth flat, or discovered the constitution of the moon or of ether or of electricity; and in this mass of rubbish it requires great skill and patience to detect such gems of value as may exist.

Continuing Neptune Discovered,

our selection from Pioneers of Science by Sir Oliver Lodge published in 1893. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in three easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Neptune Discovered.

Time: 1846

Place: (disputed)

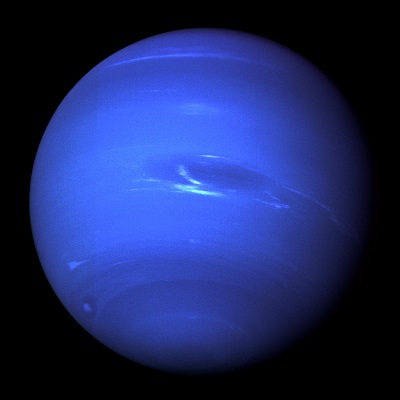

Public domain image from NASA

The errors of Uranus, though small, were enormously greater than other things which had certainly been observed; there was an unmistakable discrepancy between theory and observation. Some cause was evidently at work on this distant planet, causing it to disagree with its motion as calculated according to the law of gravitation. If the law of gravitation held exactly at so great a distance from the sun, there must be some perturbing force acting on it besides all the known forces that had been fully taken into account. Could it be an outer planet? The question occurred to several, and one or two tried to solve the problem, but were soon stopped by the tremendous difficulties of calculation.

The ordinary problem of perturbation is difficult enough: Given a disturbing planet in such and such a position, to find the perturbations it produces. This was the problem that Laplace worked out in the Mécanique Céleste.

But the inverse problem–given the perturbations, to find the planet that causes them–such a problem had never yet been attacked, and by only a few had its possibility been conceived. Friedrich Bessel made preparations for solving this mystery in 1840, but he was prevented by fatal illness.

In 1841 the difficulties of the problem presented by these residual perturbations of Uranus excited the imagination of a young student, an undergraduate of Cambridge — John Couch Adams by name — and he determined to make a study of them as soon as he was through his tripos. In January, 1843, he was graduated as senior wrangler, and shortly afterward he set to work. In less than two years he reached a definite conclusion; and in October, 1845, he wrote to the astronomer-royal, at Greenwich, Professor Airy, saying that the perturbations of Uranus could be explained by assuming the existence of an outer planet, which he reckoned was now situated in a specified latitude and longitude.

We know now that had the astronomer-royal put sufficient faith in this result to point his big telescope at the spot indicated and begin sweeping for a planet, he would have detected it within 1-3/4º of the place assigned to it by Adams. But anyone in the situation of the astronomer-royal knows that almost every post brings absurd letters from ambitious correspondents, some of them having just discovered perpetual motion, or squared the circle, or proved the earth flat, or discovered the constitution of the moon or of ether or of electricity; and in this mass of rubbish it requires great skill and patience to detect such gems of value as may exist.

Now this letter of Adams’s was indeed a jewel of the first water, and no doubt bore on its face a very different appearance from the chaff of which I have spoken; but still Adams was unknown: he had been graduated as senior wrangler, it is true, but somebody must be graduated as senior wrangler every year, and a first-rate mathematician is not produced every year. Those behind the scenes–as Professor Airy of course was, having been a senior wrangler himself — knew perfectly well that the labeling of a young man on his taking his degree is much more worthless as a testimony to his genius and ability than the general public is apt to suppose.

Was it likely that a young and unknown man should have solved so extremely difficult a problem? It was altogether unlikely. Still, he should be tested: he should be asked for explanations concerning some of the perturbations which Professor Airy had noticed, and see whether he could explain these also by his hypothesis. If he could, there might be something in his theory. If he failed–well, there was an end of it. The questions were not difficult. They concerned the error of the radius vector. Adams could have answered them with perfect ease; but sad to say, though a brilliant mathematician, he was not a man of business. He did not answer Professor Airy’s letter.

It may seem a pity to many that the Greenwich equatorial was not pointed at the place, just to see whether any foreign object did happen to be in that neighborhood; but it is no light matter to derange the work of an observatory, and alter the plans laid out for the staff, into a sudden sweep for a new planet on the strength of a mathematical investigation just received by post. If observatories were conducted on these unsystematic and spasmodic principles they would not be the calm, accurate, satisfactory places they are.

Of course, if anyone had known that a new planet was to be found for the looking, any course would have been justified; but no one could know this. I do not suppose that Adams himself felt an absolute confidence in his attempted prediction. So there the matter dropped. Adams’s communication was pigeonholed, and remained in seclusion eight or nine months.

Meanwhile, and quite independently, something of the same sort was going on in France. A brilliant young mathematician, Urban Jean Joseph Leverrier, born in Normandy in 1811, held the post of astronomical professor at the École Polytechnique, founded by Napoleon. His first published papers directed attention to his wonderful powers; and the official head of astronomy in France, the famous Arago, suggested to him the unexplained perturbations of Uranus as a worthy object for his fresh and well-armed vigor. At once he set to work in a thorough and systematic way. He first considered whether the discrepancies could be due to errors in the tables or errors in the old observations. He discussed them with minute care, and came to the conclusion that they were not thus to be explained away. This part of the work he published in November, 1845.

He then set to work to consider the perturbations produced by Jupiter and Saturn to see whether they had been accurately allowed for, or whether some minute improvements could be made sufficient to destroy the irregularities. He introduced several fresh terms into these calculations, but none of them of sufficient importance to do more than partly explain the mysterious perturbations. He next examined the various hypotheses that had been suggested to account for them. Were they caused by a failure in the law of gravitation or by the presence of a resisting medium? Were they due to some large but unseen satellite or to a collision with some comet?

All these theories he examined and dismissed for various reasons. The perturbations were due to some continuous cause–for instance, some unknown planet. Could this planet be inside the orbit of Uranus? No, for then it would perturb Saturn and Jupiter also, and they were not perturbed by it. It must, therefore, be some planet outside the orbit of Uranus, and in all probability, according to Bode’s empirical law, at nearly double the distance from the sun that Uranus is. Finally he proceeded to determine where this planet was, and what its orbit must be to produce the observed disturbances.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.