This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Problems with Uranus.

Introduction

How does one discover a planet? This story tells us of the most difficult achievement, given the technology of that time.

This selection is from Pioneers of Science by Sir Oliver Lodge published in 1893. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Sir Oliver Lodge was a key scientist in the development of radio.

Time: 1846

Place: (disputed)

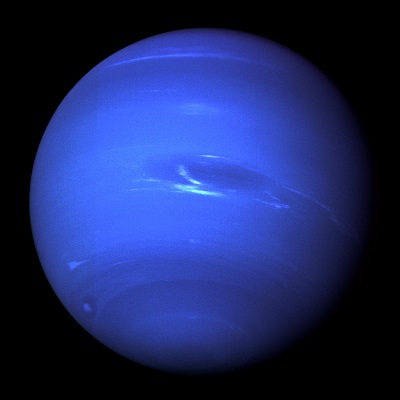

Public domain image from NASA

Among modern astronomical discoveries none has been regarded as more important than that of Neptune, the outermost known planet of the solar system. * It was a rich reward to the watchers of the sky when this new planet swam into their ken. This discovery was hailed by astronomers as “the most conspicuous triumph of the theory of gravitation.” Long after Copernicus even, the genius of philosophers was slow to grasp the full conception of a spherical earth and its relations with the heavenly bodies as presented by him. So it was also with the final acceptance of Newton’s demonstration of the universal law of gravitation (1685), whereby he showed that “the motions of the solar system were due to the action of a central force directed to the body at the center of the system, and varying inversely with the square of the distance from it.” After making this discovery, Newton himself, with the aid of others, especially of the French mathematician Picard, labored for years to verify it, and still further verification was necessary before it could be fully comprehended and accepted by the scientific world. The discovery of the asteroids or small planets revolving in orbits between those of Mars and Jupiter, aided in confirming the Newtonian theory, which the discovery of Uranus, by Sir William Herschel (1781), had done much to establish.

[* Science historians should avoid writing sentences like this. – JL]

From the time of Sir William Herschel the science of stellar astronomy, revealing the enormous distances of the stars–none of them really fixed, but all having real or apparent motions–was rapidly developed. The discovery of stellar planets, at almost incalculable distances, still further changed the aspect of the heavens as viewed by astronomers, and when the capital discovery of Neptune was made those men of science were well prepared for studying its nature and importance. These matters, as well as the simultaneous calculation of the place of Neptune by Adams and Leverrier, and its actual discovery by Galle, are set forth by Sir Oliver Lodge in a manner as charming for simplicity as it is valuable in its summary of scientific learning.

The explanation by Newton of the observed facts of the motion of the moon, the way he accounted for precession and nutation and for the tides; the way in which Laplace explained every detail of the planetary motions — these achievements may seem to the professional astronomer equally, if not more, striking and wonderful; but of the facts to be explained in these cases the general public is necessarily more or less ignorant, and so no beauty or thoroughness of treatment appeals to it or excites its imagination. But to predict in the solitude of the study, with no weapons other than pen, ink, and paper, an unknown and enormously distant world, to calculate its orbit when as yet it had never been seen, and to be able to say to a practical astronomer, “Point your telescope in such a direction at such a time, and you will see a new planet hitherto unknown to man” — this must always appeal to the imagination with dramatic intensity, and must awaken some interest in the dullest.

Prediction is no novelty in science; and in astronomy least of all is it a novelty. Thousands of years ago Thales, and others whose very names we have forgotten, could predict eclipses, but not without a certain degree of inaccuracy. And many other phenomena were capable of prediction by accumulated experience. A gap between Mars and Jupiter caused a missing planet to be suspected and looked for, and to be found in a hundred pieces. The abnormal proper-motion of Sirius suggested to Bessel the existence of an unseen companion. And these last instances seem to approach very near the same class of prediction as that of the discovery of Neptune. Wherein, then, lies the difference? How comes it that some classes of prediction–such as that if you put your finger in fire it will be burned–are childishly easy and commonplace, while others excite in the keenest intellects the highest feelings of admiration? Mainly, the difference lies, first, in the grounds on which the prediction is based; second, in the difficulty of the investigation whereby it is accomplished; third, in the completeness and the accuracy with which it can be verified. In all these points, the discovery of Neptune stands out as one among the many verified predictions of science, and the circumstances surrounding it are of singular interest.

Three distinct observations suffice to determine the orbit of a planet completely, but it is well to have the three observations as far apart as possible so as to minimize the effects of minute but necessary errors of observation. When Uranus was found old records of stellar observations were ransacked with the object of discovering whether it had ever been unwittingly seen before. If seen, it had been thought, of course, to be a star–for it shines like a star of the sixth magnitude, and can therefore be just seen without a telescope if one knows precisely where to look for it and if one has good sight–but if it had been seen and catalogued as a star it would have moved from its place, and the catalogue would by that entry be wrong. The thing to do, therefore, was to examine all the catalogues for errors, to see whether the stars entered there actually existed, or whether any were missing. If a wrong entry were discovered, it might of course have been due to some clerical error, though that is hardly probable considering the care spent in making these records, or it might have been a tailless comet, or possibly the newly found planet.

The next thing to do was to calculate backward, to see whether by any possibility the planet could have been in that place at that time. Examined in this way the tabulated observations of Flamsteed showed that he had unwittingly observed Uranus five distinct times; the first time in 1690, nearly a century before Herschel discovered its true nature. But more remarkable still, Le Monnier, of Paris, had observed it eight times in one month, cataloguing it each time as a different star. If only he had reduced and compared his observations, he would have anticipated Herschel by twelve years. As it was, he missed it. It was seen once by Bradley also. Altogether it had been seen twenty times.

These old observations of Flamsteed and those of Le Monnier, combined with those made after Herschel’s discovery, were very useful in determining an exact orbit for the new planet, and its motion was considered thoroughly known. For a time Uranus seemed to travel regularly, and as expected, in the orbit which had been calculated for it; but early in the present century it began to be slightly refractory, and by 1820 its actual place showed quite a distinct discrepancy from its position as calculated with the aid of the old observations. It was thought at first that this discrepancy must be due to inaccuracies in the older observations, and they were accordingly rejected, and tables prepared for the planet based on the newer and more accurate observations only. But by 1830 it became apparent that it did not coincide with even these. The error amounted to about 20″. By 1840 it was as much as 90″, or a minute and a half. This discrepancy is quite distinct, but still it is very small; and had two objects been in the heavens at once, the actual Uranus and the theoretical Uranus, no unaided eye could possibly have distinguished them or detected that they were other than a single star.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.