With great difficulty Montesarchio and Satriano escaped the rage of the populace.

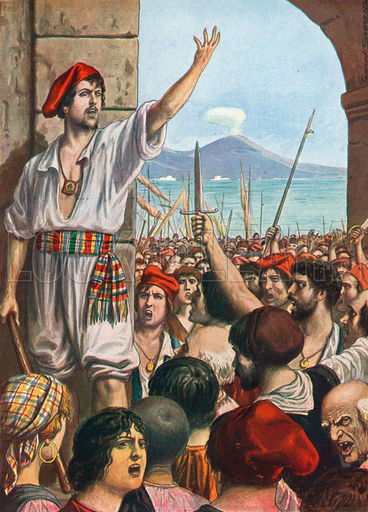

Continuing Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples,

our selection from The Carafa of Maddaloni Naples under Spanish Rule by Alfred Von Reumont published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in twelve easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Masaniello’s Revolt At Naples.

Time: 1647

Place: Naples

Public domain image from Wikipedia

But others said, and indeed with more justice, that the acquaintance which he had with Domenico Perrone was the real cause of it; for this man had been first a leader of sbirri and then of banditti, and Diomed Carafa had had a great deal to do with both. However this might be, the Viceroy summoned him: he was to go to the great market-place and try to conclude a peace with the leaders of the people. There should be no further mention of his crimes or of punishment: Don Giuseppe Carafa was also received again into favor.

The Duke mounted his horse and rode with several noblemen to the market-place. Arrived there, he employed all his eloquence. In the name of the Viceroy he promised free trade in all articles of food, and a general pardon. At first Maddaloni was well received. He was but too well known to many of the insurgents, and his mad conduct had procured him followers as well as enemies; but as he only repeated the same promises which had been made by the others, the crowd were out of humor. “No deceitful promises!” screamed a thousand voices; “the privileges, the privileges of Charles V.”

These privileges had long possessed the minds of the people. During the disturbances under the Duke of Ossuna many fabulous tales had been told about them. Genuino had then, as now, brought them forward. Not only freedom from taxes was contained in them, but an equality of power between the people and the nobility in the affairs of the town, by increasing the votes of the first, and by conceding a right of veto on resolutions affecting the people through the intervention of their deputies. This privilege they would have. This the Viceroy should confirm to them. They all screamed at the same time, but at last Maddaloni obtained a hearing. He promised to bring them the document — he would ask the Viceroy for it without delay. He was glad to escape the crowd, who prevented either himself or his horse from moving.

Negotiations for peace could not check the fury of the people or its mania for destruction. As on the day before they had demolished the custom-houses, now the houses of all who had lately become rich were destroyed. They had already begun on the previous evening, but this was only a prelude. Masaniello, who had not left the market-place the whole day, drew up a catalogue, in concert with his associates, of all the houses and palaces the effects of which were to be destroyed. Many noblemen who believed that they might have some influence with the mob, had ridden and driven to the market-place, but they returned home without accomplishing anything, or went again to Castelnuovo, where numbers of them took refuge from the pressure of necessity.

In the evening the flames burst forth in all parts of the town; much valuable property was sacrificed amid the rejoicings of the frantic populace, who screamed: “That is our blood; so may those burn in hell who have sucked it out of us!” As on Sunday the Jesuits and Theatines, now the Dominicans tried to appease the people. Their long processions were to be seen in the square of the obelisk, moving on to the houses of Sangro, Saluzzo, and Carafa, with burning torches; but the populace interrupted their prayers and litanies with angry words and many reproaches, and sent them home. Till late in the night the brilliantly lighted churches were filled with agonized supplicants.

Early on the morning of July 9th, a more dreadful scene took place than on either of the earlier days. The destruction began at daybreak. All the property of the counsellor Antonio Miroballo, in the Borgo de’ Vergini, was burning before his palace. Andrea Naclerio had caused the best furniture to be removed. The people traced it, destroyed it, dashed to pieces everything in the house and in the adjoining beautiful garden. At Alphonso Valenzano’s everything that he possessed was ruined. In a place of concealment two small casks were found full of sequins, a box containing precious pearls, and a small packet of bills of exchange — it was all thrown into the fire. All the rich and noble persons who were concerned in the farming of tolls, as well as all members of the government, saw their houses demolished. Five palaces of the secretary-general of the kingdom, the Duke of Caivano, together with those of his sons, were burned. In one of them at Santa Chiara the valuable pictures which that noble, a lover of the fine arts, had collected, were destroyed — the carpets of silk-stuff interwoven with gold, the sumptuous silver vessels, and every sort of work of art, the worth of which was valued at more than fifty thousand ducats. The mob had already become so brutal that they stabbed the beautiful horses in their stalls and threw the lapdogs into the flames, while they trampled down the rare plants in the gardens and heaped up the trees for funeral piles. Above forty palaces and houses were consumed by the flames on this day, or were razed to the ground, while the unhappy possessors looked on from the forts and watchtowers of Castelnuovo upon the rapid conflagration, heard the threatening of the alarm-bells and drums, and the howlings of the unbridled populace, among which many thieves were pursuing their business and filling their pockets with plunder. News came out of the neighborhood that the peasants were rising on all sides, and that many beautiful castles belonging to illustrious noblemen were already in flames.

Stupefied by the uproar, by the advice of a hundred counsellors, by a two-days’ insurrection, the Duke of Arcos did not nevertheless give up the attempt at a reconciliation. Certainly he risked nothing by it, for he had no other means in his power; but the hazard to the noblemen who delivered his messages was so much the greater. With great difficulty Montesarchio and Satriano escaped the rage of the populace. Six cavaliers were enclosed by barricades, and only regained their freedom by promising to obtain the transmission of their privileges. To oblige the Viceroy the Duke of Maddaloni rode once more into the market-place, carrying with him a manifesto according to which all the gabelles which had been introduced since the time of Charles V were abolished, and a general amnesty granted for the crimes already committed. Scarcely had Diomed Carafa read the paper when the tumult began again worse than before.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.