This series has twelve easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Before the Revolt.

Introduction

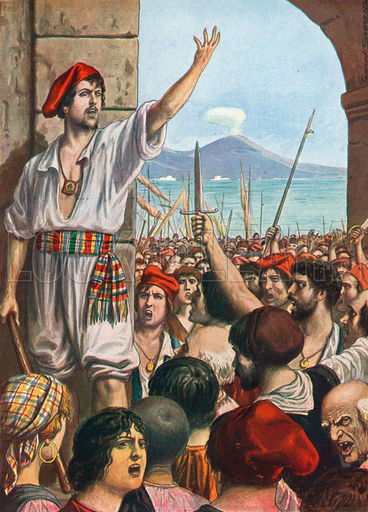

Among the various popular insurrections in Naples, the most memorable in violence and in effective results is that which Masaniello headed. Naples, with Sicily, was then subject to Spain, and a Spanish viceroy governed there. Popular discontent had already shown itself in tumults. These were provoked by various acts of oppression, but especially by burdensome taxation and the draining of the province of men for the Spanish service.

At the same time Naples was subject to French intrigue. It was the aim of Cardinal Mazarin, the successor of Richelieu as prime minister of France, to seize the rich Spanish possessions, Naples and Sicily. He foresaw the coming insurrection, and prepared to take advantage of it. Although his schemes added to the Neapolitan complications, he was not to profit by them as he hoped.

Finally, in Naples the half-smothered spirit of revolt broke out when Spain imposed a duty on fruits, raising the cost of productions upon which the majority of the people depended for subsistence.

This selection is from The Carafa of Maddaloni Naples under Spanish Rule by Alfred Von Reumont published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Reumont, the master of Italian history, brings out in full light the circumstances and consequences of Masaniello’s rising.

Time: 1647

Place: Naples

Public domain image from Wikipedia

In May, 1647, a rebellion broke out in Palermo among the lower class of people, which the viceroy, Don Pedro Fajardo Marquis de Los Veles, was not in a condition to resist. The constant increase of the taxes on articles of food, which, especially in the manner in which they were then raised, were the most felt and the most burdensome kind of taxation for the people, excited a tumult which lasted for many months, occasioned serious dissensions between the nobility and the people, and was only subdued by a mixture of firmness and clemency on the part of the Cardinal Trivulzio, the successor of Los Veles. The news of the disturbances in Sicily reached Naples, when everything there was ripe for an insurrection, which had for a long time been fermenting, and agitating men’s minds.

On all sides the threatening indications increased. Notices posted upon the walls announced that the people of Naples would follow the example of the inhabitants of Palermo if the gabelles were not taken off, especially the fruit tax, which pressed the hardest upon the populace; the better the season was, the more the poor felt themselves debarred from the enjoyment of a cheap and cooling food. The Viceroy was stopped by a troop of people as he was going to mass at the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine; he extricated himself from his difficulty as well as he could, laid the blame on the nobility who had ordered the tax, and promised what he never intended to perform. The associations of nobles assembled, but they could not agree. Some were of opinion that the tax should be kept, because the change would interfere with their pecuniary interests; others because the money asked for by the government could not otherwise be procured.

Notwithstanding these unfavorable circumstances the Duke of Arcos, the Spanish Viceroy of Naples, allowed most of the Spanish and German troops to march into Lombardy; he was deliberating how to meet the attack of the French in the North of Italy without considering that he was stripping the country of armed forces at a moment when the continuance of the Spanish rule was more than ever in jeopardy.

On the great market-place at Naples, the scene of so many tragedies and so many disturbances, stood a miserable cottage, with nothing to distinguish it from the others but the name and arms of Charles V, which were placed on the front wall. Here a poor fisherman lived, Tommaso Aniello, generally called by the abbreviated name of Masaniello. His father, Francesco or Cicco, came from the coast of Amalfi, and had married in 1620 Antonia Gargano, a Neapolitan woman.

In the Vico Rotto, by the great market, which is only inhabited by the poorest people, and where the pestilence began in the year 1656, four months later, the son was born who was destined to act so remarkable a part. Tommaso Aniello was baptized in the parish church of Sta. Catherina in Foro on June 20, 1620. On April 25, 1641, he married Bernardina Pisa, a maiden from the neighborhood of that town. Their poverty was so great that often Masaniello could not even follow up his trade of a fisherman, but earned a scanty livelihood by selling paper for the fish to be carried in. He was of middle height, well made and active; his brilliant dark, black eyes and his sunburnt face contrasted singularly with his long, curly, fair hair hanging down his back. Thus his cheerful, lively conversation agreed but little with his grave countenance. His dress was that of a fisherman, but as he is, in general, considered a remarkable person — whatever may be thought of the part he performed — so he understood, in spite of the meanness of his attire, by his arrangement and his choice of colors, to give it a peculiarity that stamped it in the memory of his contemporaries. The life of this remarkable man — a nine-days’ history — clearly shows us that he possessed wonderful presence of mind and a spirit that knew not fear.

It happened, once, in the midst of the discontent which was everywhere excited by the exorbitant increase of taxation, that Masaniello’s wife was detained by the keepers of the gate while she was endeavoring to creep into the town with a bundle of flour done up in cloths to look like a child in swaddling-clothes. She was imprisoned, and her husband, who loved her much, only succeeded in obtaining her liberation after eight days. Almost the whole of his miserable goods went to pay the fine which had been imposed upon her. Thus hatred was smouldering in the mind of Masaniello, and the flame was stirred when he — it is not known how — quarrelled with the Duke of Maddaloni’s people and was ill used by them in an unusual manner. Then the idea seems to have occurred to him to avenge himself by the aid of the people.

Many have related that instigators were not wanting. Giulio Genuino is named, formerly the favorite of the Duke of Ossuna, who, after he had encountered the strangest fate, and after wearing the chain of a galley slave at Oran on the coast of Barbary, had returned an aged man, in the habit of an ecclesiastic to his native country, meditating upon new intrigues as the old ones had failed; also a captain of banditti and a lay brother of the Carmine, who gave Masaniello money, were among the conspirators. Perhaps all this was only an attempt to explain the extraordinary fact. This much only is known with certainty, that Masaniello sought to collect a troop of boys and young people, who, among the numerous vagrant population, thronged the market and its neighborhood from the adjacent districts, as whose leader he intended to appear, as had often been done before, at the feast of the Madonna of Carmel, which takes place in the middle of July.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.