The colonists now found that by driving Philip to extremity they had roused a host of unexpected enemies.

Continuing King Philip’s War,

our selection from History of the United States by Richard Hildreth published in 1853. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in King Philip’s War.

Time: 1675

Place: Massachusetts

The colonists now found that by driving Philip to extremity they had roused a host of unexpected enemies. The River Indians, anticipating an intended attack upon them, joined the assailants. Deerfield and Northfield, the northernmost towns on the Connecticut River, settled within a few years past, were attacked, and several of the inhabitants killed and wounded. Captain Beers, sent from Hadley to their relief with a convoy of provisions, was surprised near Northfield and slain, with twenty of his men. Northfield was abandoned, and burned by the Indians.

“The English at first,” says Gookin, “thought easily to chastise the insolent doings and murderous practice of the heathen; but it was found another manner of thing than was expected; for our men could see no enemy to shoot at, but yet felt their bullets out of the thick bushes where they lay in ambush. The English wanted not courage or resolution, but could not discover nor find an enemy to fight with, yet were galled by the enemy.” In the arts of ambush and surprise, with which the Indians were so familiar, the colonists were without practice. It is to the want of this experience, purchased at a very dear rate in the course of the war, that we must ascribe the numerous surprises and defeats from which the colonists suffered at its commencement.

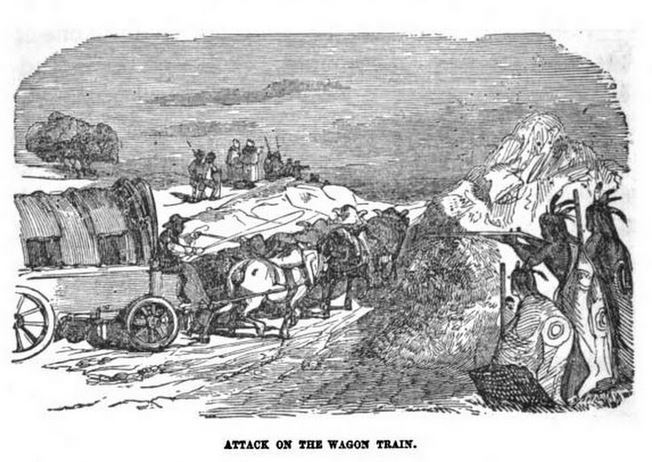

Driven to the necessity of defensive warfare, those in command on the river determined to establish a magazine and garrison at Hadley. Captain Lathrop, who had been dispatched from the eastward to the assistance of the river towns, was sent with eighty men, the flower of the youth of Essex county, to guard the wagons intended to convey to Hadley three thousand bushels of unthreshed wheat, the produce of the fertile Deerfield meadows. Just before arriving at Deerfield, near a small stream still known as Bloody Brook, under the shadow of the abrupt conical Sugar Loaf, the southern termination of the Deerfield Mountain, Lathrop fell into an ambush, and, after a brave resistance, perished there with all his company. Captain Moseley, stationed at Deerfield, marched to his assistance, but arrived too late to help him. Deerfield was abandoned, and burned by the Indians. Springfield, about the same time, was set on fire, but was partially saved by the arrival, with troops from Connecticut, of Major Treat, successor to the lately deceased Mason in the chief command of the Connecticut forces. An attack on Hatfield was vigorously repelled by the garrison.

Meanwhile, hostilities were spreading; the Indians on the Merrimac began to attack the towns in their vicinity; and the whole of Massachusetts was soon in the utmost alarm. Except in the immediate neighborhood of Boston, the country still remained an immense forest, dotted by a few openings. The frontier settlements could not be defended against a foe familiar with localities, scattered in small parties, skillful in concealment, and watching with patience for some unguarded or favorable moment. Those settlements were mostly broken up, and the inhabitants, retiring toward Boston, spread everywhere dread and intense hatred of “the bloody heathen.”

Even the praying Indians and the small dependent and tributary tribes became objects of suspicion and terror. They had been employed at first as scouts and auxiliaries, and to good advantage; but some few, less confirmed in the faith, having deserted to the enemy, the whole body of them were denounced as traitors. Eliot the apostle, and Gookin, superintendent of the subject Indians, exposed themselves to insults, and even to danger, by their efforts to stem this headlong fury, to which several of the magistrates opposed but a feeble resistance. Troops were sent to break up the praying villages at Mendon, Grafton, and others in that quarter. The Natick Indians, “those poor despised sheep of Christ,” as Gookin affectionately calls them, were hurried off to Deer Island, in Boston harbor, where they suffered excessively from a severe winter. A part of the praying Indians of Plymouth colony were confined, in like manner, on the islands in Plymouth harbor.

Not content with realities sufficiently frightful, superstition, as usual, added bugbears of her own. Indian bows were seen in the sky, and scalps in the moon. The northern lights became an object of terror. Phantom horsemen careered among the clouds or were heard to gallop invisible through the air. The howling of wolves was turned into a terrible omen. The war was regarded as a special judgment in punishment of prevailing sins. Among these sins the General Court of Massachusetts, after consultation with the elders, enumerated: Neglect in the training of the children of church members; pride, in men’s wearing long and curled hair; excess in apparel; naked breasts and arms, and superfluous ribbons; the toleration of Quakers; hurry to leave meeting before blessing asked; profane cursing and swearing; tippling-houses; want of respect for parents; idleness; extortion in shopkeepers and mechanics; and the riding from town to town of unmarried men and women, under pretense of attending lectures — “a sinful custom, tending to lewdness.”

Penalties were denounced against all these offences; and the persecution of the Quakers was again renewed. A Quaker woman had recently frightened the Old South congregation in Boston by entering that meeting-house clothed in sackcloth, with ashes on her head, her feet bare, and her face blackened, intending to personify the small-pox, with which she threatened the colony, in punishment for its sins.

About the time of the first collision with Philip, the Tarenteens, or Eastern Indians, had attacked the settlements in Maine and New Hampshire, plundering and burning the houses, and massacring such of the inhabitants as fell into their hands. This sudden diffusion of hostilities and vigor of attack from opposite quarters made the colonists believe that Philip had long been plotting and had gradually matured an extensive conspiracy, into which most of the tribes had deliberately entered for the extermination of the whites. This belief infuriated the colonists and suggested some very questionable proceedings.

It seems, however, to have originated, like the war itself, from mere suspicions. The same griefs pressed upon all the tribes; and the struggle once commenced, the awe which the colonists inspired thrown off, the greater part were ready to join in the contest. But there is no evidence of any deliberate concert; nor, in fact, were the Indians united. Had they been so, the war would have been far more serious. The Connecticut tribes proved faithful, and that colony remained untouched. Uncas and Ninigret continued friendly; even the Narragansetts, in spite of so many former provocations, had not yet taken up arms. But they were strongly suspected of intention to do so, and were accused by Uncas of giving, notwithstanding their recent assurances, aid and shelter to the hostile tribes.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.