This series has four easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Causes of the Liberal Growth in Persia.

Introduction

Although it seems impossible now, there was a moment when it seemed that Persia (modern Iran) was going to be a liberal democracy. At the time these contemporaries wrote their reports, all of the Russian intervention, the Shah’s rule, and the Ayatollah’s revolution and the Islamic fundamentalist’s rule all lay in the future.

The selections are from:

- his article in The American Missionary Review by Samuel M. Jordan.

- by Stanley White.

- an article in The Review by Emile J. Dillon.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Summary of daily installments:

| Samuel M. Jordan’s installments: | 0.5 |

| Stanley White’s installments: | 2.5 |

| Emile J. Dillon’s installments: | 1 |

| Total installments: | 4 |

We begin with Samuel M. Jordan (1871-1952). He was missionary in Iran.

Time: 1907

Place: Teheran

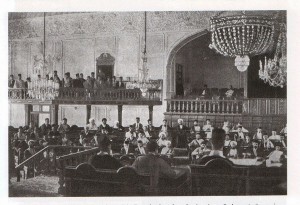

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The East is awaking. Even the law of the Medes and Persians has altered. Within the past few months the world has been surprised by the Shah’s proclamation of a constitution and the assembling of the first Persian parliament.

To those who have lived in that country and have been observing the growth of liberality this change was not entirely unexpected, for we have been able to discern the causes behind this liberal movement.

The first cause to be noted is the Persian character itself. Think of the liberality of that Zoroastrian king of Persia, Cyrus the Great, who chose the conquered Croesus to be his bosom friend and trusted counselor; who returned the Children of Israel to the Holy Land, restored the vessels of silver and gold which Nebuchadnezzar had carried away to Babylon, and gave the command for rebuilding the Temple at Jerusalem. Think of the liberality of those Zoroastrian priests who came to bring their gold and frankincense and myrrh to lay at the feet of Him who was born King of the Jews in Bethlehem of Judea. To the Greek all others were barbarians and to the Jew they were Gentiles, but Persian priests from afar came to worship a babe born in a foreign land of an alien people who they knew was to become the leader of a rival religion.

This independence of thought has borne fruit since the Mohammedan invasion. Islam has failed to hold the Persian in unreasoning faith as it has held other peoples. The Persian people as a whole are Shiah — that is, Protestant Mohammedans — and the Shiah sect in Persia has broken up into countless divisions, just as Protestant Christianity has divided into many denominations. One of these sects, the Babi — or rather, the Behai — has for the past fifty years been the second of the important factors in bringing on the movement toward liberality. In fact, the Behais would scarcely admit that they are a sect of Mohammedans, since they claim that their religion is the step next higher than Islam in the evolution of the one true religion which previously found expression in the Law of Moses, the Gospel of Christ, and the Koran.

The third factor in the liberal movement that I would mention is the prosperity of Christian nations. Mohammedanism is a politico-religious institution, political even more than religious. Therefore the blessings of temporal prosperity should of right belong to the faithful. The early successes of their so-called religious wars were quite in accord with these Christian nations they are unable to find a satisfactory explanation. Into the midst of all these liberal tendencies in solution at the psychological moment came the Russo-Japanese War to crystallize them into action. During the war all the Persian papers were full of the wonderful progress of Japanese in the past forty years. It was the never-ending theme of conversation where two or three of the educated class chanced to meet. A history of Japan compiled and translated by a graduate of our school in Teheran had a large sale. The papers were full of essays on the blessings of constitutional liberty and freedom. The surprising thing was that Japan’s growth in power and her consequent victories over Russia were attributed not only to education, civilization, and advancement in arts and sciences, but also to constitutional liberty, freedom of speech and of the press, and even to religious liberty, and America’s part in this development was frequently referred to. The liberal tendency of the Persian press and the liberality of the Persian government were illustrated by the leading paper in Teheran publishing as serials biographies of Washington and Franklin.

He was a college president.

The first rumblings of a coming revolution were heard in Persia toward the close of 1906, when disturbances in Teheran followed political agitation on the part of Moslems and ecclesiastics. The material out of which a republic could be made did not exist, and while the desire was budding, there were none among the younger element made of the stuff out of which strong, sane, political leaders of the future might come.

With the year 1907, and before any one supposed it possible, the changes in Persia began to occur with astonishing rapidity. Shah Muzaffar-ed-Din died and was succeeded by his son, Mohammed Ali. It was feared there would be wide popular disturbances, but the change was made very quietly. Before the death of Muzaffar-ed-Din the movement toward constitutional government, which was supposed to be a mere temporary and unimportant disturbance, actually materialized. About the middle of July some influential merchants and priests, or mullahs, began pressing the Sadrazam (Prime Minister) for the institution of financial and political reforms, threatening to cause disturbances should their demands not be granted. The troops were called out, and on reaching the bazaars they found a big crowd, clamoring and threatening. The soldiers were ordered to fire on the mob and, having done so, some sixty or seventy people were killed, the rest dispersing as fast as they could. Next day the chief mullahs left the city on their way to Kum (a holy city), and about 1,000 merchants and sayids with students rushed into the British Legation, putting themselves in bast (asylum). The following day the people at the Legation had increased to 3,000. They were all well received, tents were given to them, and by the end of the week the number had increased to 10,000 and it kept increasing daily till it reached 18,000. All the gardens, stable yards, etc., were full and all streets leading to the Legation were overcrowded. The people refused to leave until the mullahs had been brought back in honor from Kum, and a dast-i-khat (autograph firman) from the Shah given to them granting all their demands. The principal demands were as follows:

- Dismissal of the Sadrazam (Prime Minister).

- Dismissal of an offensive official, the Amir-i-Bahadur- i-Jang.

- A representative assembly, to be named by the people, to direct the affairs of state.

- General financial reforms.

| Master List | Next—> |

Emile J. Dillon begins here.

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Like!! I blog frequently and I really thank you for your content. The article has truly peaked my interest.