Today’s installment concludes Persia’s 1907 Revolution,

the name of our combined selection from Samuel M. Jordan, Stanley White, and Emile J. Dillon. The concluding installment, by Emile J. Dillon from an article in The Review.

Emile J. Dillon (1854-1933) was an expert in Asian languages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed selections from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Persia’s 1907 Revolution.

Time: 1907

Place: Teheran

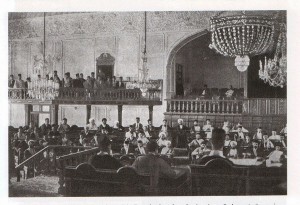

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Shoolookh, or “ructions,” which the good people of Teheran had so long been looking forward to and even hoping for, have come at last and cleared the air. Persia, after a comedy of errors and a tragedy of follies, has received the long-wished- for constitution from the hands of outsiders, the nation is now free to govern or misgovern itself, and its first act was to take a child of thirteen for ruler. But the Persian problem does not appear to have been solved as yet. One can hardly say that it is much nearer to a reasonable solution than it was three months ago. Peace and quiet have, we are told, come to stay, and that is a blessing to be thankful for. Truly. But it would not be amiss to postpone payment of the debt of gratitude until actual delivery. The close of the first, or call it second, act of the Iranian drama was full of incongruities, tragedy alternating with comedy in a droll, whimsical sequence. On Monday, the 12th of July, 1909, the Shah’s position was strong and hopeful. His troops had defeated the forces of the Sipahdar, the chief Constitutional leader, in the open field, and now surrounded them on three sides. The Sipahdar felt discouraged, and if the Shah’s troops had profited by their successes and pressed him close there is little doubt he would have had to abandon the struggle. In fact, he ought to have abandoned it already. But he relied on the folly of his foes. And in this he was right. For the Persian royal guard, or Cossack brigade, which was fresh and brisk after the truce, seems to have suddenly lost the use of its eyes and ears and hands. Accordingly the Sipahdar marched through the encircling lines of the enemy without difficulty or danger and approached Teheran, where they gave a signal, agreed upon beforehand, which was to have brought the population of the capital to their assistance. But the people of Teheran were also deaf and blind and paralyzed; only a few appeared outside the walls to lead the champions of Persia’s liberty into the city.

Colonel Liakhoff’s resistance is described as noisy but in effectual. Powder was burned in prodigious quantities, and heavy guns boomed continuously; but Allah was merciful to the combatants. Colonel Liakhoff lost only 27 and the Nationalists 30 men. Pillage was indulged in by all sides. In the Allauddowleh street, where several legations and hotels are situated, house after house was entered and gutted. The first in the field were the Shah’s soldiers. Very soon, however, gendarmes and police were dispatched to seize and punish these malefactors. But in presence of the rich booty the hearts of the constables melted, and they fraternized with the defenders of the Shah and set to plunder likewise. Cossacks were then ordered to put an end to these disorders and to shoot the refractory without ruth. But the Cossacks on their arrival in Allauddowleh Street divided, one section of them helping the Shah’s soldiers to rob and destroy, while the remainder allied themselves with the police and helped them to sack and pillage. They were resolved, however, to commit no act of violence under a foreign flag, lest diplomatic trouble should ensue. That lesson had been well impressed upon them. Accordingly they respectfully removed all flags that had been hoisted over private houses, and only then did they go on with their work unfearingly.

All this time the strategical position of the revolutionists underwent no sensible improvement. At any moment the Shah’s Bakhtiari allies might enter the city and worst the Nationalists as badly as they had done a few days before near Karatepe. In order to put an end, if possible, to this painful state of suspense and danger, the Sipahdar and his lieutenants resolved to try their luck at intimidating the monarch. That would give them victory. An ultimatum was drafted, signed, and dispatched, summoning the Shah to send representatives to hold parley with the Nationalists respecting the terms of an understanding. In case of refusal they threatened to resume hostilities, and repudiated responsibility for the consequences. It was the stereotyped formula, with no new considerations to lend it weight, but the Shah, it was thought, might be in the mood to argue just then.

Meanwhile the news which the unlucky ruler had been receiving from his messengers was depressing. The outlook for the royal troops was systematically painted in somber colors. By whom? It has been hinted that the representatives of the Powers were aware of this exaggeration and of its motive. But all the Ministers Plenipotentiary were absent just then from Teheran, taking their summer rest at a place about eight miles from the capital. All except the Austrian charge d’affaires, who, on the 14th of July, having heard that Europeans, and especially European women, were in danger, went about from house to house, occasionally under fire, taking not only Austrian subjects but others as well, and giving them the shelter and hospitality of his Legation. That man deserves recognition. The next night the Shah had lain awake, a prey to constant terror. Early on the morning of the 16th he sent his wife and family for safety to the Russian Mission in carriages. He himself followed on horseback, accompanied by the tutor of his son, a Russian named Smirnoff. By circuitous paths they reached the Russian Legation at Zerghende, and at nine in the morning Mohammed Ali Shah entered that Russian territory and invoked the protection of the Russian flag. Finis.

About two hours later the ultimatum was brought to the palace, and the fact elicited that his Majesty had quitted Sultanetabad and taken refuge at the Russian Legation. Among the deputies of the Medjliss there was great joy at this happy and unexpected turn of events. The thorniest of all questions — the role to be allotted to the Shah — was here settled to the hearts’ content of the Nationalists, and by the same stroke of good fortune all their most pressing difficulties were removed as by the waving of a magician’s wand. The Powers, too, had good grounds for feeling relieved. But the ill-starred ruler to whom the tidings were brought, together with the additional communication that he had been deposed by the “Supreme Council,” raged and fumed like one bereft of reason. He had himself to blame. Like his colleague, Abdul Hamid, he had no faith in his mission, was not fitted for the business of kingship. “Fear made gods; boldness created kings.” Mohammed Ali Shah, refusing to accept his deposition, announced that he had abdicated by the fact that he had sought shelter under the Russian flag.

The election of a successor to Mohammed Ali was the affair of a couple of hours. The “Supreme Council” — the rebels of yesterday being transformed into the despots of today — elected the Shah’s favorite son, Sultan-Ahmet, a pretty boy of thirteen, whom carriage, gait, and demeanor render incomparably more dignified, more kingly than his father. The child had been a witness of the brusk way in which his parent had been treated, and when he was told that the same insolent fellows had raised him to the vacant throne he proudly said he would never be their Shah. And this resolve was approved by Mohammed Ali. But the child’s Russian tutor insisted; Court dignitaries bade him be brave and quit him of his caprices, and the boy burst into tears and sobbed hysterically. Finally he was soothed and induced to leave the refuge of the Russian Legation and repair to Sultanetabad. The next day but one a ukase was promulgated in the name of the little Shah and addressed to the Regent, which opens with this characteristic and significant passage: “Your Highness! The most High Creator has delivered into our hands the reins of government and chosen our person to be the defender and protector of holy Islam.” On the 19th and 20th of July the child had a difficult part to play, and he played it admirably. Conveyed to Teheran in a carriage made mostly of glass and drawn by six milk-white Arab steeds, he had to make his way to the palace through a dense and undisciplined crowd.

Next day the Salaam, or homage to the sovereign, was arranged in the garden. The spectators, including the troops and foreigners of distinction, were legion. The child Shah, in uniform, encumbered by an enormous sword glittering with jewels, sat on a golden throne. With downcast eyes and changeful voice he uttered a few words about the will of Allah, the monarchical power, and his own good intentions. The oldest courtier replied in “high-faluting” language, expressing the same wishes, forecasting the same roseate destinies for monarch and nation that he had expressed to the child’s father two short years ago. Vanitas vanitatum. Pale, immobile, and seemingly attentive, the little Shah sat there until the flowery discourse was done; then he put his hand to his head gear in military fashion, arose from the armchair, and walked slowly into the inner apartments, accompanied by a patriarchal figure that might have been an Old Testament prophet, but was only the Prince Regent. The poetic prolog was now over, and the next step was toward the prosaic work of administering the constitutional realm of Iran.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our selections on Persia’s 1907 Revolution by three of the most important authorities on this topic:

- his article in The American Missionary Review by Samuel M. Jordan published in .

- by Stanley White published in .

- an article in The Review by Emile J. Dillon published in .

Samuel M. Jordan begins here. Stanley White begins here. Emile J. Dillon begins here.

This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.