Today’s installment concludes Assyrian Empire Destroyed,

our selection from Ancient History of the East by Francois Lenormant and by Emile Chevallier published in 1881.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of three thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Assyrian Empire Destroyed

Time: 612 BC

Place: Nineveh

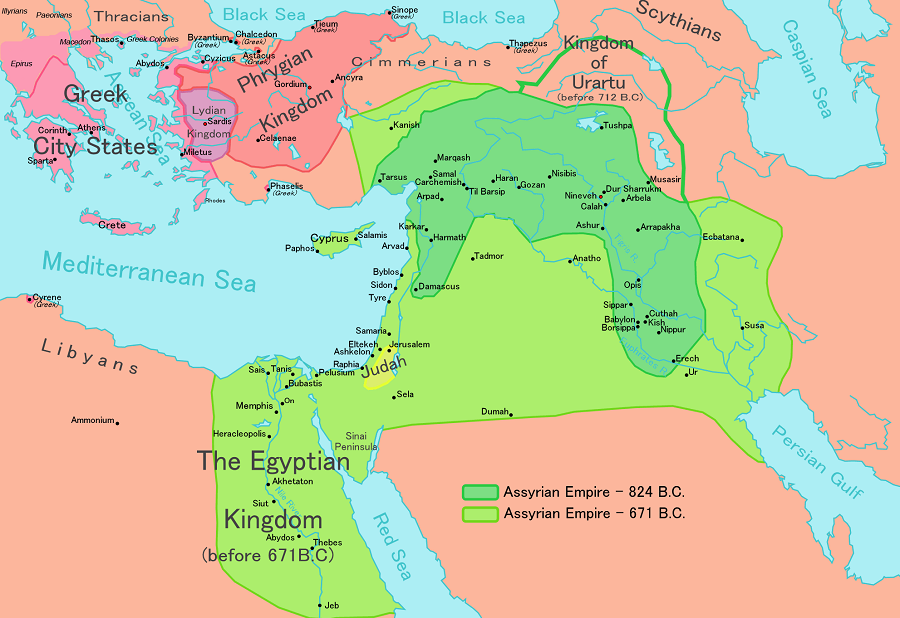

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Sardanapalus had entirely given himself up to the orgies of his harem, and never left his palace walls, entirely renouncing all manly and warlike habits of life. He had reigned thus for seven years, and discontent continued to increase; the desire for independence was spreading in the subject provinces; the bond of their obedience each year relaxed still more, and was nearer breaking, when Arbaces, who commanded the Median contingent of the army and was himself a Mede, chanced to see in the palace at Nineveh the King, in a female dress, spindle in hand, hiding in the retirement of the harem his slothful cowardice and voluptuous life.

He considered that it would be easy to deal with a prince so degraded, who would be unable to renew the valorous traditions of his ancestors. The time seemed to him to have come when the provinces, held only by force of arms, might finally throw off the weighty Assyrian yoke. Arbaces communicated his ideas and projects to the prince then ietrusted with the government of Babylon, the Chaldæan Phul (Palia?), surnamed Balazu (the Terrible), a name the Greeks have made into Belesis; he entered into the plot with the willingness to be expected from a Babylonian, one of a nation so frequently rising in revolt.

Arbaces and Balazu consulted with other chiefs, who commanded contingents of foreign troops, and with the vassal kings of those countries that aspired to independence; and they all formed the resolution of overthrowing Sardanapalus. Arbaces engaged to raise the Medes and Persians, while Balazu set on foot the insurrection in Babylon and Chaldæa. At the end of a year the chiefs assembled their soldiers, to the number of forty thousand, in Assyria, under the pretext of relieving, according to custom, the troops who had served the former year.

When once there, the soldiers broke into open rebellion. The tablet in the British Museum tells us that the insurrection commenced at Calah in B.C. 792. Immediately after this the confusion became so great that from this year there was no nomination of an eponyme.

Sardanapalus, rudely interrupted in his debaucheries by a danger he had not been able to foresee, showed himself suddenly inspired with activity and courage; he put himself at the head of the native Assyrian troops who remained faithful to him, met the rebels, and gained three complete victories over them.

The confederates already began to despair of success, when Phul, calling in the aid of superstition to a cause that seemed lost, declared to them that if they would hold together for five days more, the gods, whose will he had ascertained by consulting the stars, would undoubtedly give them the victory.

In fact, some days afterward a large body of troops, whom the King had summoned to his assistance from the provinces near the Caspian Sea, went over, on their arrival, to the side of the insurgents and gained them a victory. Sardanapalus then shut himself up in Nineveh, and determined to defend himself to the last. The siege continued two years, for the walls of the city were too strong for the battering machines of the enemy, who were compelled to trust to reducing it by famine. Sardanapalus was under no apprehension, confiding in an oracle declaring that Nineveh should never be taken until the river became its enemy.

But, in the third year, rain fell in such abundance that the waters of the Tigris inundated part of the city and overturned one of its walls for a distance of twenty stades. Then the King, convinced that the oracle was accomplished and despairing of any means of escape, to avoid falling alive into the enemy’s hands constructed in his palace an immense funeral pyre, placed on it his gold and silver and his royal robes, and then, shutting himself up with his wives and eunuchs in a chamber formed in the midst of the pile, disappeared in the flames.

Nineveh opened its gates to the besiegers, but this tardy submission did not save the proud city. It was pillaged and burned, and then razed to the ground so completely as to evidence the implacable hatred enkindled in the minds of subject nations by the fierce and cruel Assyrian government. The Medes and Babylonians did not leave one stone upon another in the ramparts, palaces, temples, or houses of the city that for two centuries had been dominant over all Western Asia.

So complete was the destruction that the excavations of modern explorers on the site of Nineveh have not yet found one single wall slab earlier than the capture of the city by Arbaces and Balazu. All we possess of the first Nineveh is one broken statue. History has no other example of so complete a destruction.

The Assyrian empire was, like the capital, overthrown, and the people who had taken part in the revolt formed independent states — the Medes under Arbaces, the Babylonians under Phul or Balazu, and the Susianians under Shutruk-Nakhunta. Assyria, reduced to the enslaved state in which she had so long held other countries, remained for some time a dependency of Babylon.

This great event occurred in the year B.C. 789.

[When the noble sculptures and vast palaces of Nimrud had been first uncovered, it was natural to suppose that they marked the real site of ancient Nineveh; a passage of Strabo, and another of Ptolemy, lent confirmation to this theory. Shortly afterward a rival claimant started up in the region farther to the north.

“After a while an attempt was made to reconcile the rival claims by a theory the grandeur of which gained it acceptance, despite its improbability. It was suggested that the various ruins, which had hitherto disputed the name, were in fact all included within the circuit of the ancient Nineveh, which was described as a rectangle, or oblong square, eighteen miles long and twelve broad. The remains at Khorsabad, Koyunjik, Nimrud, and Keremles marked the four corners of this vast quadrangle, which contained an area of two hundred and sixteen square miles — about ten times that of London!

“In confirmation of this view was urged, first, the description in Diodorus, derived probably from Ctesias, which corresponded (it was said) both with the proportions and with the actual distances; and, next, the statements contained in the Book of Jonah, which, it was argued, implied a city of some such dimensions. The parallel of Babylon, according to the description given by Herodotus, might fairly have been cited as a further argument; since it might have seemed reasonable to suppose that there was no great difference of size between the chief cities of the two kindred empires.” — Rawlinson.]

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Assyrian Empire Destroyed by Francois Lenormant and Emile Chevallier from their book Ancient History of the East published in 1881. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.