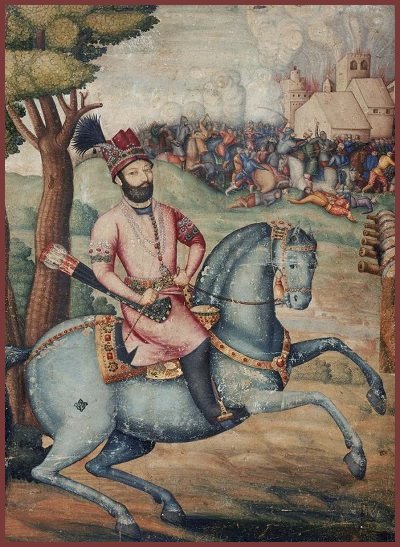

Today’s installment concludes Nadir Shah Captures Delhi,

our selection from History of Persia by Sir John Malcolm published in 1815. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of eleven thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Nadir Shah Captures Delhi.

Time: 1747

Public domain image from Wikipedia

The flattering historian of Nadir expressly informs us that that sovereign was deceived, by the gross misrepresentations of infamous men, into the commission of this great crime. The European physician who attended that monarch during the latter years of his life asserts the innocence of Reza Kuli. He adds that Nadir was so penetrated with remorse after the deed of horror was done that he vented his fury on all around him; and fifty noblemen, who had witnessed the dreadful act, were put to death on the pretext that they should have offered their lives as sacrifices to save the eyes of a prince who was the glory of their country. It is also to be remarked that the impressions which have been transmitted regarding a fact comparatively recent are all against Nadir, who is believed to have had no evidence of his son’s guilt but his own suspicions. From the moment that his life had been attempted in Mazandaran that monarch had become gloomy and irritable. His bad success against the Lesghis had increased the natural violence of his temper and, listening to the enemies of Reza Kuli, he, in a moment of rage, ordered him to be blinded.

“Your crimes have forced me to this dreadful measure,” was, we are told, the speech that Nadir made to his son. “It is not my eyes you have put out,” replied Reza Kuli, “but those of Persia.” The prophetic truth of this answer sunk deep into the soul of Nadir; and we may believe his historian, who affirms that he never afterward knew happiness nor desired that others should enjoy it. All his future actions were deeds of horror, except the contest which he carried on against the Turks for three years; and even in it he displayed none of that energy and heroic spirit which marked his first wars with that nation.

The Persian army had made unsuccessful efforts to reduce the cities of Basra, of Bagdad, and of Mussul. Nadir marched early in the succeeding year to meet a large Turkish force which had advanced to near Erivan; and we are told that he desired to encounter his enemies in battle on the same plain where he had ten years before acquired such renown; but their general, subdued by his own fears, fled and was massacred by his soldiers; who, thrown into confusion at this event, were easily routed by the Persians. This was the last victory of Nadir, and it was gained merely by the terror of his name. Sensible of his own condition he hastened to make peace. His pretensions regarding the establishment of a fifth sect among orthodox Mahometans and the erection of a fifth pillar in the Mosque of Mecca were abandoned. It was agreed that prisoners on both sides should be released; that Persian pilgrims going to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina should be protected; and that the whole of the provinces of Iraq and Azerbaijan should remain with Persia, except an inconsiderable territory that had belonged to the Turkish government in the time of Shah Ismail, the first of the Suffavean kings.

The conduct of Nadir to his own subjects during the last five years of his reign had been described, even by a partial historian, as exceeding in barbarity all that has been recorded of the most bloody tyrants. The acquisition of the wealth of India had at first filled the mind of this monarch with the most generous and patriotic feelings. He had proclaimed that no taxes should be collected from Persia for three years. But the possession of riches had soon its usual effect of creating a desire for more; and while the vast treasures he had acquired were hoarded at the fort of Kelat, which, with all the fears of a despot, he continually labored to render inaccessible, he not only paid his armies, but added to his golden heaps, from the arrears of remitted revenue, which he extorted with the most inflexible rigor.

Nadir knew that the attack which he had made upon the religion of his country had rendered him unpopular, and that the priests, whom he peculiarly oppressed, endeavored to spread disaffection. This made him suspect those who still adhered to the tenets of the Shiah sect, or, in other words, almost all the natives of Persia. The troops in his army upon whom he placed most reliance were the Afghans and Tartars, who were of the Sunni persuasion. Their leaders were his principal favorites; and every pretext was taken to put to death such Persian chiefs as possessed either influence or power. These proceedings had the natural effect of producing rebellion in every quarter, and the spirit of insurrection which now displayed itself among his subjects changed the violence of Nadir into outrageous fury. His murders were no longer confined to individuals: the inhabitants of whole cities were massacred; and men, to use the words of his historian, left their abodes, and took up their habitations in caverns and deserts, in the hope of escaping his savage ferocity. We are told–and the events which preceded render the tale not improbable–that when on his march to subdue one of his nephews who had rebelled in Sistan, he proposed to put to death every Persian in his army. There can be little doubt that his mind was at this moment in a state of frenzy which amounted to insanity. Some of the principal officers of his court, who learned that their names were in the list of proscribed victims, resolved to save themselves by the assassination of Nadir. The execution of the plot was committed to four chief men who took advantage of their stations, and, under the pretext of urgent business, rushed past the guards into the inner tents, where the tyrant was asleep. The noise awoke him; and he had slain two of the meaner assassins, when a blow from Salah Beg deprived him of existence.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Nadir Shah Captures Delhi by Sir John Malcolm from his book History of Persia published in 1815. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Nadir Shah Captures Delhi here and here and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.