Nadir claimed, as a prize which he had won, the wealth of the Emperor and a great proportion of that of his richest nobles and subjects.

Continuing Nadir Shah Captures Delhi,

our selection from History of Persia by Sir John Malcolm published in 1815. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5-minute installments.

Previously in Nadir Shah Captures Delhi.

Time: 1739

Place: Delhi

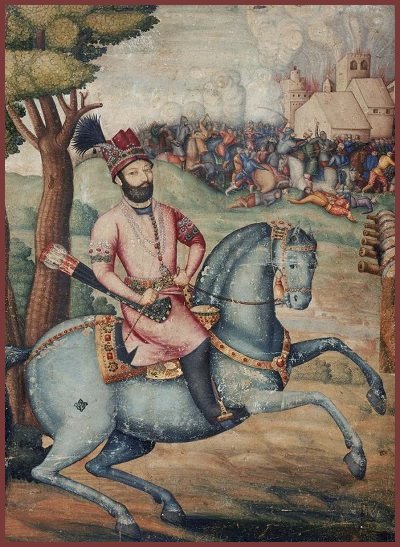

Public domain image from Wikipedia

When the Emperor was approaching, as we ourselves are of a Turkoman family, and Mahomet Shah is a Turkoman and the lineal descendant of the noble house of Gurgan, we sent our dear son, Nassr Ali Khan, beyond the bounds of our camp to meet him. The Emperor entered our tents, and we delivered over to him the signet of our empire. He remained that day a guest in our royal tent. Considering our affinity as Turkomans, and also reflecting on the honors that befitted the majesty of a king of kings, we bestowed such upon the Emperor, and ordered his royal pavilions, his family, and his nobles to be preserved; and we have established him in a manner equal to his great dignity.

At this time the Emperor, with his family and all the lords of Hindustan, who marched from camp, are arrived in Delhi; and on Thursday, the 29th of Zilkadeh, we moved our glorious standard toward that capital.

It is our royal intention, from the consideration of the high birth of Mahomet Shah, of his descent from the house of Gurgan, and of his affinity to us as a Turkoman, to fix him on the throne of the empire and to place the crown of royalty upon his head. Praise be to God, glory to the Most High, who has granted us the power to perform such an action! For this great grace which we have received from the Almighty we must ever remain grateful.

God has made the seven great seas like unto the vapor of the desert, beneath our glorious and conquering footsteps and those of our faithful and victorious heroes. He has made in our royal mind the thrones of kings and the deep ocean of earthly glory more despicable than the light bubble that floats upon the surface of the wave; and no doubt his extraordinary mercy, which he has now shown, will be evident to all mankind.”

The facts stated in this letter are not contradicted either by Persian of Indian historians; though the latter find reasons for the great defeat of their countrymen suffered at Karnal, in the rashness of some of their leaders and the caution of others; and they state that even after the victory the conqueror would have returned to Persia on receiving two millions sterling, if the disappointed ambition of an Indian minister had not urged him to advance to Delhi. But it is not necessary to seek for causes for the overthrow of an army who were so panic-struck that they fled at the first charge, and nearly twenty thousand of whom were slain with hardly any loss to their enemies; and our knowledge of the character of Nadir Shah forbids our granting any belief to a tale which would make it appear that the ultimate advantages to be obtained from this great enterprise, and the unparalleled success with which it had been attended, depended less upon his genius than upon the petty jealousies and intrigues of the captive ministers of the vanquished Mahomet Shah.

The causes which led Nadir to invade India have been already stated; nor were they groundless. The court of Delhi had certainly not observed the established ties of friendship. It had given shelter to the Afghans who fled from the sword of the conqueror; and this protection was likely to enable them to make another effort to regain their lost possessions, and consequently to reinvolve Persia in war. The ambassadors of Nadir, who had been sent to make remonstrances on this subject, had not only been refused an answer, but were prevented from returning, in defiance of the reiterated and impatient applications of that monarch. This proceeding, we are told, originated more in irresolution and indecision than from a spirit of hostility; but it undoubtedly furnished a fair and justifiable pretext for Nadir’s advance. Regarding the other motives which induced him to undertake this enterprise, we can conjecture none but an insatiable desire of plunder, a wish to exercise that military spirit he had kindled in the Persians, or the ambitious view of annexing the vast dominions of the sovereign of Delhi to the crown of Persia. But if he ever cherished this latter project he must have been led by a near view of the condition of the empire of India, to reject it as wholly impracticable. We are, however, compelled to respect the greatness of that mind which could resolve, at the very moment of its achievement, upon the entire abandonment of so great a conquest; for he did not even try to establish a personal interest at the court of Delhi, except through the operation of those sentiments which his generous conduct in replacing him upon his throne might make upon the mind of Mahomet Shah.

Nadir claimed, as a prize which he had won, the wealth of the Emperor and a great proportion of that of his richest nobles and subjects. The whole of the jewels that had been collected by a long race of sovereigns, and all the contents of the imperial treasury, were made over by Mahomet Shah to the conqueror. The principal nobles, imitating the example of their monarch, gave up all the money and valuables which they possessed. After these voluntary gifts, as they were termed, had been received, arrears of revenue were demanded from distant provinces, and heavy impositions were laid upon the richest of the inhabitants of Delhi. The great misery caused by these impositions was considerably augmented by the corrupt and base character of the Indian agents employed, who actually farmed the right of extortion of the different quarters of the city to wretches who made immense fortunes by the inhuman speculation, and who collected, for every ten thousand rupees they paid into Nadir’s treasury, forty and fifty thousand from the unhappy inhabitants, numbers of whom perished under blows that were inflicted to make them reveal their wealth; while others, among whom were several Hindus of high rank, became their own executioners rather than bear the insults to which they were exposed, or survive the loss of that property which they valued more than their existence.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.