This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Italy Establishes its First Base in Africa.

Introduction

After the Italian nation unified it joined the European scramble for colonies in the rest of the world. Italy set out to establish its hegemony of a part of Africa. Unlike the other European powers in the late nineteenth century, Italy’s effort fell short. Some Italians thought that their country had been cheated out of the spoils of Europe’s spectacular dominance over much of the rest of the world. This climate of opinion eventually will lead to the Fascists and Mussolini.

This selection is from special article for Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 19 by Frederick Augustus Edwards published in 1905. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Time: February 5, 1885

Place: Massowah, Eritrea

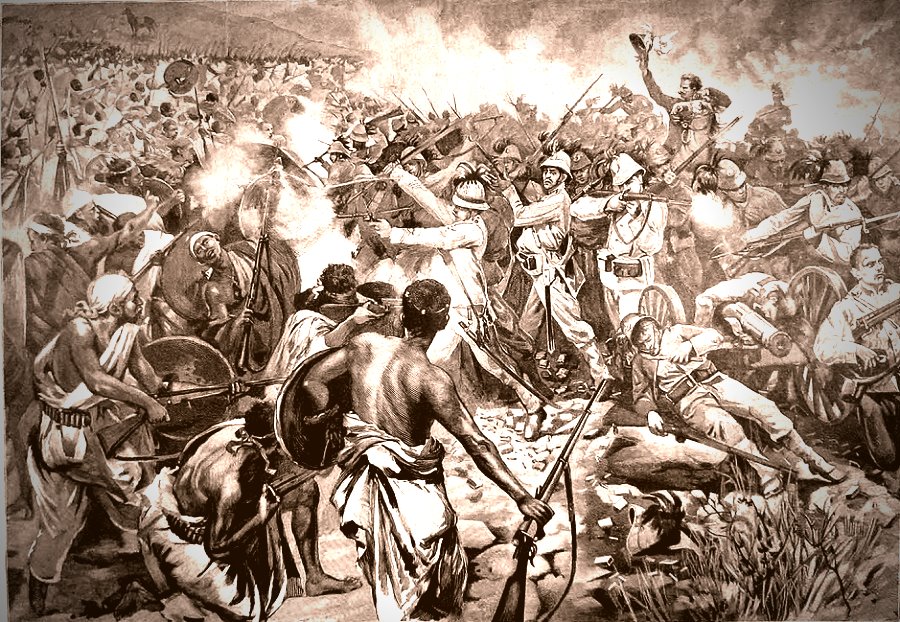

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Italy has been by no means fortunate in her colonial policy. Since she has become a united nation, she has entered, with the other great Powers of Europe, into the general ” scramble for Africa,” which characterized the closing decade of the nineteenth century, but has sadly burned” her fingers in so doing. It is evident that she has not yet developed a genius for what Continental nations understand as colonizing. For this is altogether different from British methods. Continental people do not go out and settle down upon the land as the English do, but rely more upon the action of their governments, and then regard the acquired territories more as possessions than as colonies.

Italy’s first steps in this direction were not turned toward Tripoli, which might naturally have been regarded as her most probable concern in Africa; she looked toward the Red Sea for her first footing on the Dark Continent.

The beginnings of the Italian colonial policy were for a time shrouded in mystery, but came about in this way. Professor Joseph Sapeto, of the University of Genoa, who had paid many visits to the Danakil and Somali coasts, conceived the idea of establishing in the neighborhood of the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb a maritime station and port of call, which would serve also as a point from which to open up commercial relations between Italy and Eastern Africa. He impressed his views on the Government, which commissioned him in the autumn of 1869 to find a suitable place. Accordingly he went out, accompanied by the Minister of Marine, and, as a result, Assab Bay was selected, on the African coast of the Red Sea, opposite Moka. The bay provided a good anchorage, a line of islands and coral reefs forming a protection from the southeast monsoon. No town was there — only a miserable agglomeration of huts inhabited by a few hundred natives. This part of the coast is inhabited by the Danakils, a nomadic race, without a well-defined political organization and owning no subjection to the Porte or to the Khedive. To avoid foreign complications and keep the real object secret, the pur chase was made in the name of the Rubattino Steamship Company. The bay, with its islands and a strip of territory on the mainland, was purchased from the local sultan, Berehan, for six thousand Marie-Therese dollars (November 15, 1869). But the ruse was not effective; the Khedive protested against the acquisition as a violation of his rights, and Italy, not wishing to risk a conflict, allowed the matter to fall into abeyance.

After ten years, however, it was resolved to make the transfer effective, and on December 26, 1879, the Sultan Berehan formally made over the territories to the Rubattino company, the Egyptian Governor of the Red Sea coasts making an ineffectual protest. The appointment of the Chevalier Branchi (January, 1881) as Civil Commissary at Assab identified the Italian Government with the transfer of sovereignty, and Assab was soon declared an Italian colony.

One of the first attempts to penetrate into the interior was made in the same year by Giuletti, secretary to the Civil Commissary, who, accompanied by Lieutenant Biglieri and several seamen, left Beilul, a small port north of Assab (May, 1881) ; but, after five or six days’ journey, the little party was surprised by Danakils and massacred. This proved only the first of a series of fatalities that have befallen the Italians in East Africa. Two years later an attempt to cross the same region in the reverse direction was made by Gustave Bianchi, who had accompanied the Marquis Antinori on his scientific mission to Shoa, and had traversed Abyssinia from south to north. To give the Italians liberty to travel through the Danakil country, which, like a great wedge, separates Abyssinia from the sea, a treaty was concluded (March, 1883) with Mahomet, the Anfari (or sultan) of Aussa, who maintained some sort of rule over the greater part of the Danakil tribes. But the faith with which the Anfari acted seems ever to have been very questionable, and perhaps he thought the success of the Italians was not consistent with his own interests.

Bianchi, after a short sojourn in Abyssinia, where he had been well received by the Negus, set out from Makalle (September 22, 1884) with two companions (Diana and Monari) and an escort of eight men, hoping to reach Assab by a direct route. But the little party was betrayed by a Tigre guide, and was massacred by the Danakils (October 7th). The news of this outrage was received with great indignation in Italy, and the Government immediately decided to dispatch an expedition to punish the murderers.

But meanwhile events were happening in the Sudan which completely altered the aspect of affairs. The insurrection of the Mahdi and the withdrawal of the Egyptian Government, at the instigation of England, from the Sudan provinces involved also — though the necessity is not apparent — the Egyptian possessions on the Red Sea coast; and the punishment of the murderers of Bianchi was soon lost sight of in the effort to profit by the weakness of Egypt, to seize some of the positions that were falling from the Khedive’s grasp. This was the time, in fact, for an effective move in the “scramble for Africa”; and the ample troops sent out from Italy quickly threw off the cloak under which they were dispatched. On February 5, 1885, Admiral Caimi raised the Italian flag at Massowah, disregarding the protest of the Egyptian Governor, but leaving, for the sake of appearances, the Egyptian flag floating alongside. Then came the occupation of Beilul, quickly followed by that of Arafali (a little town at the head of the Bay of Adulis); Arkiko, near Massowah; the Hauakil Islands, to the south of the Bay of Adulis; Edd; and Mader, at the head of the Bay of Amphila. The appearance of Egyptian authority was not kept up long, and the garrisons of the Khedive were peaceably deported back to Egypt.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.