Why had Belgium been so unwilling to undertake the administration of the Congo on terms involving thorough reforms?

Continuing Reform of the Congo Horror,

with a selection from North American Review by John Daniels. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. This selection is presented in three easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Reform of the Congo Horror.

Time: 1908

Place: Congo

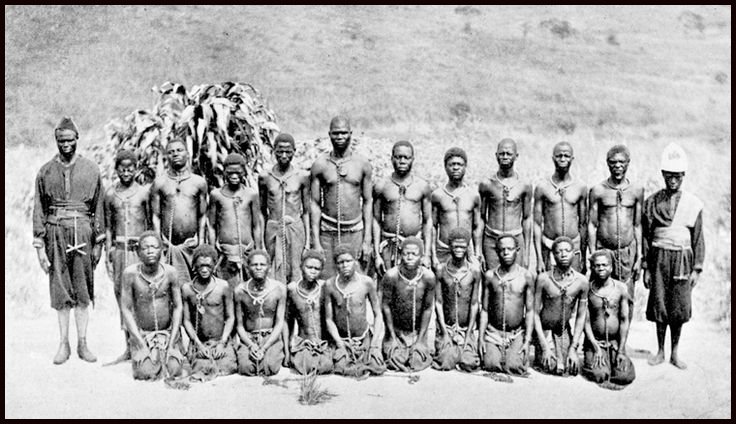

Public domain image

The report of the Commission of Inquiry shows that the great underlying iniquities in the Free State are: first, the wholesale theft by the “State” of all the land except the merest hut-spaces, leaving the natives landless in their own country; secondly, as a necessary concomitant of the theft of the land, the seizure of all the produce of the land with which the natives might and should engage in legitimate trade for their own betterment, and by the almost total lack of which they are rendered possessionless in their own country; thirdly, the enforcement upon the natives of a so-called tax in labor (that being, as the Congo officials naively contend, the only commodity left to the natives with which to pay taxes) which is so enormous, as actually enforced, that it keeps the natives at work for the State almost incessantly, making of them at last slaves in their own country.

The sections of the Commission’s Report which describe in details these workings of the Congo system have been often quoted and are easily accessible to the public. Permission has been gained to incorporate in this statement evidence to the same effect from an equally reliable and still more recent source, which is not yet accessible to the public; this evidence being that contained in the official reports to the State Department of Consul- General Slocum, his successor, Consul- General Smith, and Vice-Consul-General Memminger. Mr. Smith in his report states that on the basis of an actual experiment he made in having rubber collected under the most favorable conditions, with the native collectors the best that could be selected by one of the state’s officials, and the locality one of the richest in rubber, he found that given such conditions the payment of the state’s tax would require “nineteen days and five hours each month, or practically two hundred and thirty-six days each year.” This under ideal conditions! With natives less skillful in collecting and laboring in localities where rubber is less plentiful, it can easily be conceived that the wretched Congolese must work for the state almost every day in the year.

Summing up these conditions, Consul-General Slocum wrote from the Congo in December, 1906: “I have the honor to report that I find the Congo Free State, under the present regime, to be nothing but a vast commercial enterprise for the exploitation of the products of the country, particularly that of ivory and rubber.” And Mr. Memminger wrote: “In general, the condition of the people in the upper Congo seemed unhappy, and led to the conclusion that the system of government under which the natives must live does not promote their welfare. In its operation, the system seems to be one in which considerations of humanity and benevolence are least important.”

But why, one may now be impelled to ask, is Belgium so unwilling to undertake the administration of the Congo on terms involving thorough reforms and giving effect to the humane provisions of the Berlin and Brussels Acts? This innocent query strikes down to the very root of the evil. The answer may be given in brief compass. King Leopold has achieved world-wide repute as a promoter and financier of extraordinary ability. The Congo Free State is his supreme business success. The profits yielded by the merciless rubber system to Leopold and his copartners, in their non-official capacity as chief shareholders in the concessionary companies, are, as is proved even by the published figures, enormous. The Belgians have won fame only as a nation of keen merchants and traders. Leopold’s business associates in the Congo investment include many of the foremost citizens of Belgium. Undoubtedly the institution of genuine reforms in the Free State would appreciably diminish the profits from the colony and might even necessitate temporary grants-in-aid. Leopold and his fellow stockholders in the rubber companies are averse to any reduction in their present profits. Leopold’s dividend- loving subjects are not only disinclined to be money-out in the Congo bargain, but see in it no contemptible opportunity for increased income. The net result of this hearty accord between the business king and his business people is that Belgium, unforced, will not introduce reforms in the Congo. On the contrary, as the Catholic Mirror, of Baltimore, has pithily expressed it, “It is wholly unlikely that the Belgium administration will spare any efforts to maintain the highly lucrative status quo.”

If Belgium, therefore, proves unwilling to undertake the administration of the Congo on conditions consistent with humanity, either some form of international control, carrying out the ideal expressed in 1885, when the Free State was founded, or partition among the Powers holding contiguous territory in Africa would have to be adopted as a remedy of last resort. But whatever the final outcome, one thing is certain: The “Congo Free State,” and all that this ghastly misnomer has come to mean, must go.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

John Daniels begins here. M. Van Housen begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.