Fortunately, Menelik did not seek to follow up his victory by carrying the war into the Italian colony, or the consequences would have been still more serious.

Continuing Italy in Africa 1896,

our selection from special article for Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 19 by Frederick Augustus Edwards published in 1905. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Italy in Africa 1896.

Time: 1896

Place: Adwa

Public domain image from Wikipedia

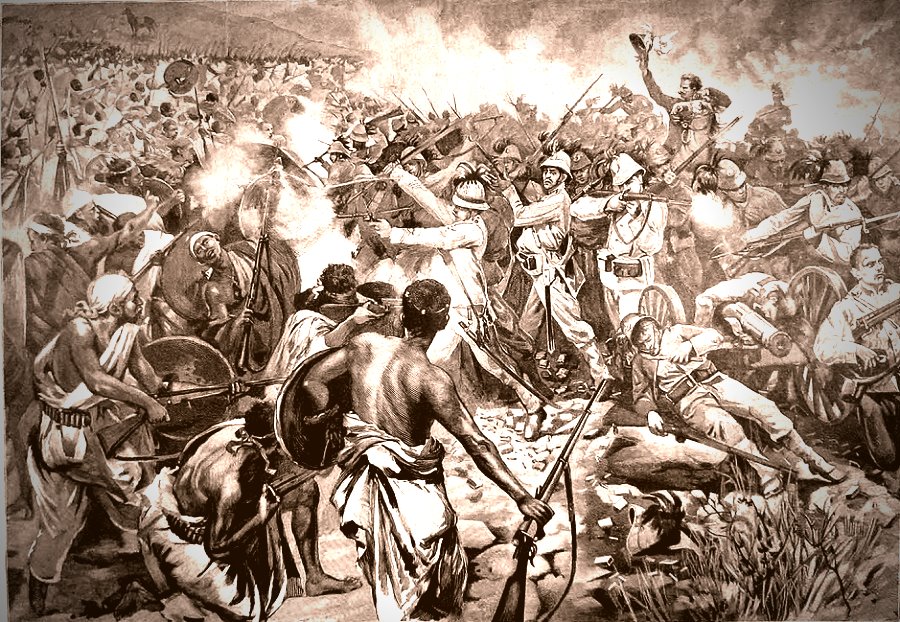

The early hours of March 1st found the Italian army advancing in four columns, wending their way through the intricate mountain country. Of these, the brigade under General Albertone, through some error, pushed farther up through the mountain passes than had been intended, and was cut to pieces by the countless hordes of the enemy. General Dabormida’s brigade also was separated from the rest of the force in a valley more to the northward and met a like fate; while the other two brigades found themselves utterly unable to contend with the overwhelming hordes of the Abyssinians, and those who were not cut down took to headlong flight, having no time to fire on their pursuers as they fled. So cowed was General Baratieri himself by this disastrous rout that he forgot his command, forgot to give orders to the detachments that had been guarding positions in the rear, forgot everything except to seek his own safety.

The Italian losses on this fatal day were enormous. The bodies of three thousand one hundred twenty-five Italians and five hundred eighteen natives were found and buried, besides large numbers of the native troops probably buried by the Abyssinians. Of the sixteen thousand men who took part in the engagement, probably five thousand fell on the field of battle, and three thousand died of their wounds or were killed by the Abyssinians during their flight, and from three thousand to four thou sand were taken prisoners. Of the four generals of brigade, Arimondi and Dabormida were dead, Albertone was a prisoner, and Ellena wounded. All the artillery was captured in the combat or was abandoned at the beginning of the retreat. But the Italians sold their lives dearly, and the Abyssinian loss is stated at four thousand to five thousand killed and seven thousand to eight thousand wounded.

The Nemesis had come, and the Crispi Ministry, which had thus played with the lives of men and the military reputation of Italy as with pawns in a game, fell. Of course there was an attempt to make a scapegoat of General Baratieri, who had been induced, against his better judgment, to attempt the impossible, and he was at once superseded by General Baldissera. Fortunately, Menelik did not seek to follow up his victory by carrying the war into the Italian colony, or the consequences would have been still more serious. The new Italian Government came in with a desire to patch up peace as best it could, and it was now content to give up the newly annexed provinces and to fix the frontier at the Mareb-Belesa-Muna line; that is, where it was five years before. But the Negus wanted restrictions on the number of soldiers to be kept in the colony and on the erection of new fortifications; he also asked for the evacuation of Adigrat. Major Salsa, the Italian envoy, made three journeys between Massowah and the camp of the Negus without being able to come to any agreement. At last, Menelik refused any further concession, and set out for Shoa, while Ras Mangasha and Ras Alula, with twenty thousand men, besieged Adigrat. The garrison was, however, relieved by General Baldissera, after negotiations with Ras Mangasha, and Adigrat was evacuated by the Italians, the fortifications and cannon being destroyed.

Efforts were still continued to effect the release of the prisoners held by Menelik, and the Russian Colonel Leontief obtained the release of fifty of them.

A little later Dr. Nerazzini, who had visited Menelik in previous years, was sent on a similar mission, and on October 26, 1896, he concluded a treaty with Menelik at Adis-Ababa, by which he obtained far more favorable terms for Italy than might have been expected. The Treaty of Uccheli was abrogated, and the absolute independence of Abyssinia recognized. The new treaty did not specifically recognize the frontier claimed by Italy; it provided that, the contracting parties being unable to agree, the delimitation of frontiers should be effected a year later on the spot, by delegates of both governments. In the meantime the Mareb-Belesa-Muna frontier would be respected as the status quo ante. By a convention signed at the same time, Menelik agreed to send the Italian prisoners to Harar and Zeila, the Italian Government paying an equitable sum for the expenses incurred in their behalf. Menelik did not even wait for the ratification of the treaty to carry out this part of the contract, but almost at once started the prisoners on their way, making it a mark of honor of the birthday of the Queen of Italy. These prisoners had been treated with humanity while in the hands of their captors; not so the native prisoners, who suffered the usual penalty of having their right hands and left feet cut off.

Before following the latest phases of this African drama, let us turn for a moment to the great “Eastern horn” of Africa, which is also included in the Italian protectorate — an area inhabited by the Somali, an inhospitable nomadic people, whose country has only of late years been penetrated to any extent, and who are very suspicious of foreigners. In this region, to the south of Cape Guardafui, Italian influence began in 1888 with the con clusion of a treaty by the Italian Consul at Zanzibar with the Sultan of Opia. On February 9, 1889, an Italian protectorate was declared over the territory of the Sultan, and on April 7th in the same year a similar convention was signed with the Sultan of the Mijurtains, an important Somali tribe occupying the coast between Cape Guardafui and Opia. On March 24, 1891, a protocol was signed with England denning the frontier of the respective spheres of influence, the line following the river Jub from the sea to 6° north, along the sixth parallel to 350 east, and then along that meridian line to the Blue Nile. But England has also some possessions in the northern part of Somaliland, and, to prevent clashing in this direction, a new convention was entered into (May 5, 1894), by which the frontier between the English and Italian spheres is mainly represented by the eighth parallel of latitude and the forty-ninth meridian.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.