This series has four easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Systematic Oppression in the Congo.

Introduction

Belgian merchants began planting trade stations in 1876. In 1885 their labors were recognized by Europe in the establishment of the “Congo Free State” under Belgium King Leopold’s rule. By degrees, however, the world became aware that the Belgians were bringing little of civilization to the Africans, but much of cruelty and suffering. Unnamable atrocities were reported, especially in the way of “mutilations” of the natives, the cutting off of a hand or foot.

As the tale of the “Congo Horrors” waxed ever darker, public sentiment became aroused both in America and England. Congo Reform Associations sprang up in both countries; and these finally in 1908 succeeded in compelling a change, by which the irresponsible “Congo Free State” was ended. It was formally annexed to Belgium, and thus the whole region passed as a colony under the control of the Belgian Parliament.

Here are two contemporary accounts. Mr. John Daniels, who was Secretary of the American Congo Reform Association hopes that the reforms will improve conditions for the African natives. The Belgian view is then given by M. Van Hoesen in an address to the American people originally published in the Independent. M. Van Hoesen speaks for the Belgian King. His words were prefaced by the Independent with the editorial note: “We are authorized to state that if etiquette permitted King Leopold to express his views concerning the Congo controversy, they would be those which follow.”

In civil rights history, the evil words and deeds of white oppressors ought to not be white-washed. For that reason, Van Hoesen’s propaganda, as offensive as it is, is here presented.

The selections are from:

- North American Review by John Daniels.

- Address to the American People by M. Van Housen.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. There’s three installments by John Daniels and one installment by M. Van Housen.

We begin with John Daniels. He was Secretary of the American Congo Reform Association.

Time: 1908

Place: Congo

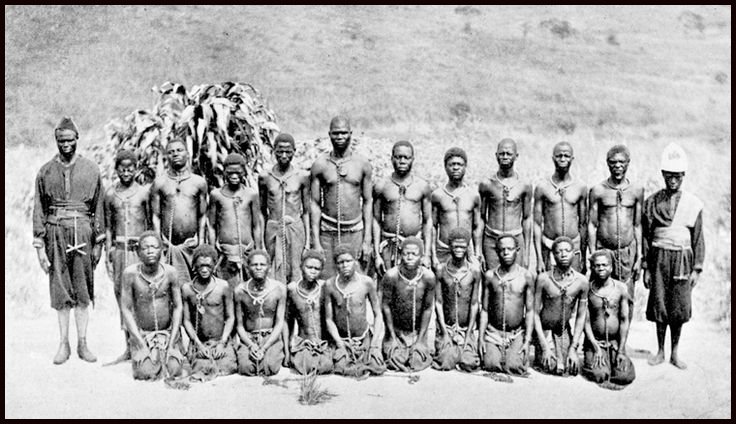

Public domain image

On August 20th, the Belgian Chamber of Deputies voted to annex the Congo Free State to Belgium as a colony. On September 9th, the Belgian Senate followed suit. The double-monarch, Leopold, King-Sovereign of the Independent State of the Congo and King of the Belgians, has, in both capacities, set his official seal to this legislative action by consenting finally to give away the Congo with one hand and receive it back with the other. Thus, after years of public agitation and governmental negotiation, the so-called “Belgian Solution” is given as an answer to the Congo Question.

The Congo Question has forced itself upon the world in two chronological stages — the first stage concerning a fact, the second a remedy. The question of fact arose in the middle nineties, as a consequence, on the one hand, of the reports of travelers, missionaries, and Government officials to the effect that the most inhuman cruelty and butchery were being practiced upon the natives of the Congo Free State, in central Africa; and, on the other hand, of the out-and-out denials of Leopold and his agents. Between the accusations and the denials, the public was at first puzzled and skeptical. But from 1895 onward the charges came in with such increasing frequency and from such an ever-greater variety of trustworthy sources as finally to compel belief, and the “Congo atrocities” became stock for common conversation. These atrocities, related in detail by those who had witnessed them, and given added vividness by actual photographs from the scene, made such an indelible impression on the popular imagination that to this day many people of the class whose knowledge of events is gained from newspaper headlines vaguely identify them with the entire Congo Question.

But, even at the outset, it was perceived by those who looked deeper that such specific outrages were only accompanying symptoms of an underlying disease to which the whole system of administration in the Congo had fallen victim. This disease was not at once fully diagnosed, but very soon it became clear that at the core it was a case of “rubber” and “profits.” Nearly all the accounts of atrocities made the attempts of the officials to force the natives to bring them more rubber for export the root of the trouble. As early as 1895, so well-qualified an observer as Mr. E. J. Glave, the explorer, wrote, after an extended journey over the State, that the basic cause of the prevailing wretched condition seemed to him to be the “frantic efforts to secure a revenue.” His insight was increasingly confirmed as time went on, and as the mass of evidence, which accumulated month by month and year by year, was analyzed, there gradually arose a public demand throughout the Western world, but most vigorously in England and the United States, in which countries Congo Reform Associations were organized in 1904, for an impartial and authoritative investigation of affairs in the Free State. The essential issue had ceased to be one of “atrocities” and had become one of the fundamental system of Congo administration.

And in November, 1905, approximately ten years after the accounts of misgovernment began to circulate, that issue was disposed of once and for all by the publication of the Report of the Congo Commission of Inquiry. The appointment of this Commission in July, 1904, had been forced upon Leopold by the increasing manifestations of public indignation, and by urgent representations from the British Government. Its three distinguished members, Edmond Jansens, Giacomo Nisco, and E. de Schumacher, spent four and a half months in the Congo, holding hearings and taking testimony in different localities. As, after their return to Europe, month succeeded month and the findings were not announced, the public began to surmise that a crushing verdict of guilty had been brought in. And so it proved when at last, after eight months’ delay, the Report was published. Its damning effect would be hard to exaggerate. Not only did it substantiate the gravest of the charges which had been made, but it went further, and reduced these various charges to their common denominator, so to speak, in an underlying Congo “system” of merciless commercial exploitation of the natives. In a word, it proved that Leopold had established not a state, in any true sense, but a gigantic trading company, with all other considerations subordinated to profits. This Report has been the Gibraltar on which the Congo Reform Movement, now grown to such proportions, has rested firmly, needing no additional foundation. Leopold and his agents have, it is true, continued to reiterate denials, and in uninformed quarters have gained some credence; but, in the light of the decisive evidence at hand, these denials are ridiculous. The conclusive character of the Report has not been more impressively put than by one of Leopold’s most distinguished Belgian subjects, Professor Felicien Cattier, of the University of Brussels, who is probably the leading authority to-day on matters of Congo administration.

In the preface to his recent book, “A Study of the Situation in the Congo Free State,” Professor Cattier said: “The publication of the Report of the Commission of Inquiry trans formed, as if by a stroke from a magic wand, the nature of the Congo Question and the direction of the discussions to which it gave rise. For a heated dispute as to the existence of abuses, it has substituted a calmer consideration of the necessary remedies.”

Four possible remedies presented themselves: the institution of thorough reforms by Leopold himself; the taking over of the Congo as a colony by Belgium; some form of international administration; partition among the Powers holding contiguous territory in Africa.

| Master List | Next—> |

M. Van Housen begins here.

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.