It was not long before sunset when the van of the royal procession entered the gates of the city.

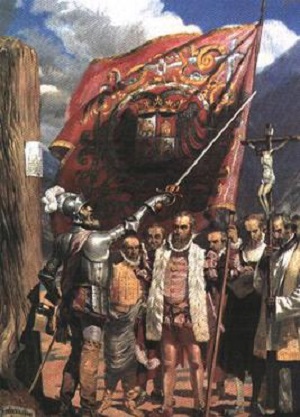

Continuing Pizarro Conquers the Incan Empire,

our selection from The Conquest of Peru by William H. Prescott published in 1847. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in 3 easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Pizarro Conquers the Incan Empire.

Time: 1532

Place: Cuzco, Peru

Fair use image from Wikipedia

It is difficult to account for this wavering conduct of Atahualpa, so different from the bold and decided character which history ascribes to him. There is no doubt that he made his visit to the white men in perfect good faith, though Pizarro was probably right in conjecturing that this amiable disposition stood on a very precarious footing. There is as little reason to suppose that he distrusted the sincerity of the strangers, or he would not thus unnecessarily have proposed to visit them unarmed. His original purpose of coming with all his force was doubtless to display his royal state, and perhaps, also, to show greater respect for the Spaniards; but when he consented to accept their hospitality and pass the night in their quarters, he was willing to dispense with a great part of his armed soldiery, and visit them in a manner that implied entire confidence in their good faith. He was too absolute in his own empire easily to suspect; and he probably could not comprehend the audacity with which a few men, like those now assembled in Cajamarca, meditated an assault on a powerful monarch in the midst of his victorious army. He did not know the character of the Spaniard.

It was not long before sunset when the van of the royal procession entered the gates of the city. First came some hundreds of the menials, employed to clear the path from every obstacle, and singing songs of triumph as they came, “which, in our ears,” says one of the conquerors, “sounded like the songs of hell!” Then followed other bodies of different ranks and dressed in different liveries. Some wore a showy stuff, checkered white and red, like the squares of a chess-board. Others were clad in pure white, bearing hammers or maces of silver or copper; and the guards, together with those in immediate attendance on the Prince, were distinguished by a rich azure livery, and a profusion of gay ornaments, while the large pendants attached to the ears indicated the Peruvian noble.

Elevated high above his vassals came the Inca Atahualpa, borne on a sedan or open litter, on which was a sort of throne made of massive gold of inestimable value. The palanquin was lined with the richly colored plumes of tropical birds, and studded with shining plates of gold and silver. The monarch’s attire was much richer than on the preceding evening. Round his neck was suspended a collar of emeralds of uncommon size and brilliancy. His short hair was decorated with golden ornaments, and the imperial borla encircled his temples. The bearing of the Inca was sedate and dignified; and from his lofty station he looked down on the multitudes below with an air of composure, like one accustomed to command.

As the leading lines of the procession entered the great square — larger, says an old chronicler, than any square in Spain — they opened to the right and left for the royal retinue to pass. Everything was conducted with admirable order. The monarch was permitted to traverse the plaza in silence, and not a Spaniard was to be seen. When some five or six thousand of his people had entered the place, Atahualpa halted, and, turning round with an inquiring look, demanded, “Where are the strangers?”

At this moment Fray Vicente de Valverde, a Dominican friar, Pizarro’s chaplain, and afterward Bishop of Cuzco, came forward with his breviary, or, as other accounts say, a Bible, in one hand and a crucifix in the other, and, approaching the Inca, told him that he came by order of his commander to expound to him the doctrines of the true faith, for which purpose the Spaniards had come from a great distance to his country. The friar then explained, as clearly as he could, the mysterious doctrine of the Trinity, and, ascending high in his account, began with the creation of man, thence passed to his fall, to his subsequent redemption by Jesus Christ, to the Crucifixion, and the Ascension, when the Saviour left the apostle Peter as his vicegerent upon earth.

This power had been transmitted to the successors of the apostle, good and wise men, who, under the title of popes, held authority over all powers and potentates on earth. One of the last of these popes had commissioned the Spanish Emperor, the most mighty monarch in the world, to conquer and convert the natives in this western hemisphere; and his general, Francisco Pizarro, had now come to execute this important mission. The friar concluded with beseeching the Peruvian monarch to receive him kindly, to abjure the errors of his own faith and embrace that of the Christians now proffered to him, the only one by which he could hope for salvation; and, furthermore, to acknowledge himself a tributary of the emperor Charles, who, in that event, would aid and protect him as his loyal vassal.

Whether Atahualpa possessed himself of every link in the curious chain of argument by which the monk connected Pizarro with St. Peter, may be doubted. It is certain, however, that he must have had very incorrect notions of the Trinity if, as Garcilasso states, the interpreter, Felipillo, explained it by saying that “the Christians believed in three gods and one God, and that made four.” But there is no doubt he perfectly comprehended that the drift of the discourse was to persuade him to resign his sceptre and acknowledge the supremacy of another.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Hernando Pizarro begins here. William H. Prescott begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.