Today’s installment concludes Ghengis Khan Founds the Mongol Empire,

our selection from History of the Mongols by Henry H. Howorth published in 1888. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of six thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Ghengis Khan Founds the Mongol Empire.

Time: 1203

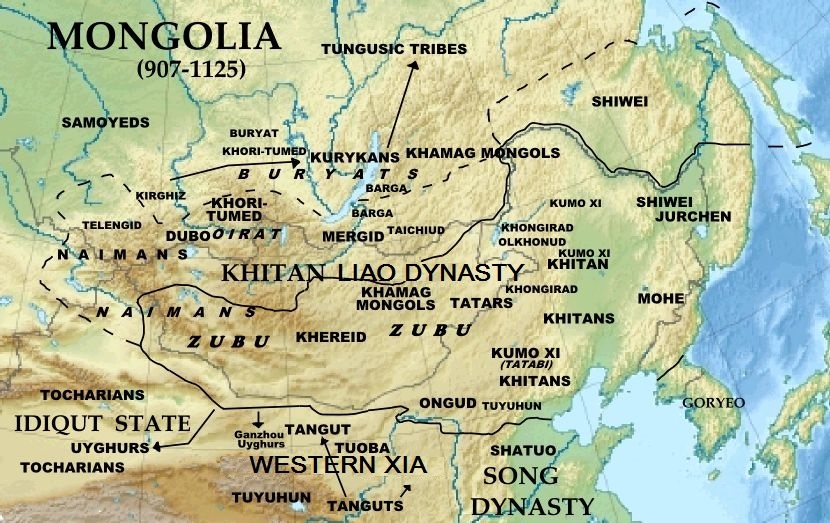

Place: Mongolia

CC BY-SA 4.0 image from Wikipedia

[Continuing his letter – jl]

5. I pounced like a jerfalcon onto the mountain Jurkumen, and thence over the lake Buyur, and I captured for you the cranes with blue claws and gray plumage, that is to say, the Durbans and Taidshuts. Then I passed the lake Keule. There I took the cranes with blue feet; that is, the Katakins, Saldjuts, and Kunkurats. This is the fifth service I have done you.

6. Do you not remember, O Khan, my father, how on the river Kara, near the mount Jurkan, we swore that if a snake glided between us, and envenomed our words, we would not listen to it until we had received some explanation? yet you suddenly left me without asking me to explain.

7. O Khan, my father, why suspect me of ambition? I have not said, ‘My part is too small, I want a greater;’ or ‘It is a bad one, I want a better.’ When one wheel of a cart breaks, and the ox tries to drag it, it only hurts its neck. If we then detach the ox, and leave the vehicle, the thieves come and take the load. If we do not unyoke it, the ox will die of hunger. Am I not one wheel of thy chariot?”

With this letter Temudjin sent a request that the black gelding of Mukuli Bahadur, with its embroidered and plated saddle and bridle, which had been lost on the day of their struggle, might be restored to him; he also asked that messengers might be sent to treat for a peace between them. Another letter was sent to his uncle Kudshir, and to his cousin Altun.

This letter is interesting, because it perhaps preserves for us some details of what took place at the accession of Genghis. It is well known that the Mongol Khan affected a coy resistance when asked to become chief. The letter runs thus: “You conspired to kill me, yet from the beginning did I tell the sons of Bartam Bahadur (i.e., his grandfather), as well as Satcha (his cousin), and Taidju (his uncle). Why does our territory on the Onon remain without a master? I tried to persuade you to rule over our tribes. You refused. I was troubled. I said to you, ‘Kudshir, son of Tekun Taishi, be our khan.’ You did not listen to me; and to you, Altun, I said, ‘You are the son of Kutluk Khan, who was our ruler. You be our khan.’ You also refused, and when you pressed it on me, saying, ‘Be you our chief,’ I submitted to your request, and promised to preserve the heritage and customs of our fathers. Did I intrigue for power? I was elected unanimously to prevent the country, ruled over by our fathers near the three rivers, passing to strangers. As chief of a numerous people, I thought it proper to make presents to those attached to me. I captured many herds, yurts, women, and children, which I gave you. I enclosed for you the game of the steppe, and drove toward you the mountain game. You now serve Wang Khan, but you ought to know that he is fickle. You see how he has treated me. He will treat you even worse.”

Wang Khan was disposed to treat, but his son Sengun said matters had gone too far, and they must fight it out. We now find Wang Khan quarrelling with several of his dependents, whom he accused of conspiring against him. Temudjin’s intrigues were probably at the bottom of the matter. The result was that Dariti Utshegin, with a tribe of Mongols, and the Sakiat tribe of the Keraits, went over to Temudjin, while Altun and Kudshir, the latter’s relations, who had deserted him, took refuge with the Naimans.

Among the companions of his recent distress, a constant one was his brother Juji Kassar, who had also suffered severely, and had had his camp pillaged by the Keraits. Temudjin had recourse to a ruse. He sent two servants who feigned to have come from Juji, and who offered his submission on condition that his wife and children were returned to him. Wang Khan readily assented, and to prove his sincerity sent back to Juji Kassar some of his blood in a horn, which was to be mixed with koumiss, and drunk when the oath of friendship was sworn. Wang Khan was completely put off his guard, and Temudjin was thus able to surprise him. His forces numbered about four thousand six hundred, and he seems to have advanced along the banks of the Kerulon, toward the heights of Jedshir, between the Tula and the Kerulon, and therefore toward the modern Urga, where Wang Khan was posted. In the battle which followed, and which was fought in the spring of 1203, the latter was defeated; he fled to the Naimans, and was there murdered. Temudjin was sincerely affected by the death of the old man.

The Naiman chief, Tayang, had his skull encased in silver and bejewelled, and afterward used it as a ceremonial cup; a custom very frequent in Mongolia. Such cups have been lately met with in Europe, one of which was exhibited at the great exhibition of 1851, where it was shown as the skull of Confucius. Another, or perhaps the same, which was encased in marvellous jeweller’s work, has been lately destroyed; the gold having been barbarously melted by the Jews. * By the death of Wang Khan, Temudjin became the master of the Kerait nation, and thus both branches of the Mongol race were united under one head.

[* This distasteful sentence is not only offensive but is an example of bad history which is entirely too prevalent in our times. If creates basic questions such as which Jew? How many of them? And most significantly of all, how do you know that other Jews approved of whoever melted the gold? – jl]

He now held a kuriltai, where he was proclaimed khan. There is some confusion about the period when he adopted the title of Genghis, but the probability is that he did so three years later. The earlier date (1203) is the one, however, from which his reign is often reckoned to have commenced.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Ghengis Khan Founds the Mongol Empire by Henry H. Howorth from his book History of the Mongols published in 1888. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Genghis Khan Founds Mongol Empire here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.