During the action, having been hit by twelve arrows, he fell from his horse unconscious

Continuing Ghengis Khan Founds the Mongol Empire,

our selection from History of the Mongols by Henry H. Howorth published in 1888. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Ghengis Khan Founds the Mongol Empire.

Time: 1194-1199

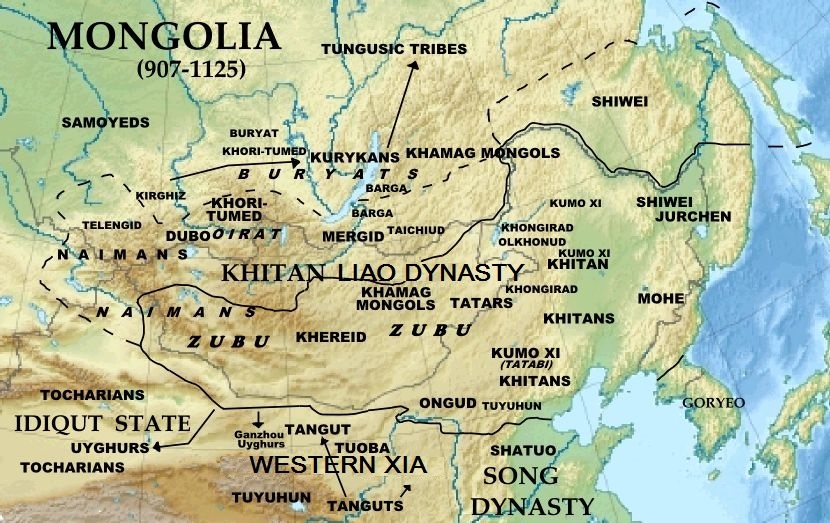

Place: Mongolia

CC BY-SA 4.0 image from Wikipedia

Temudjin now gave a grand feast on the banks of the Onon, and distributed decorations among his brothers. To this were invited Sidsheh Bigi, chief of the Burgins or Barins, his own mother, and two of his step-mothers. A skin of koumiss, or fermented milk, was sent to each of the latter, but with this distinction: in the case of the eldest, called Kakurshin Khatun, it was for herself and her family; in that of the younger, for herself alone. This aroused the envy of the former, who gave Sichir, the master of ceremonies, a considerable blow. The undignified disturbance was winked at by Temudjin, but the quarrel was soon after enlarged. One of Kakurshin’s dependents had the temerity to strike Belgutei, the half-brother of Temudjin, and wounded him severely in the shoulder, but Belgutei pleaded for him. “The wound has caused me no tears. It is not seemly that my quarrels should inconvenience you,” he said. Upon this Temudjin sent and counselled them to live at peace with one another, but Sidsheh Bigi soon after abandoned him with his Barins. He was apparently a son of Kakurshin Khatun, and therefore a step-brother of Temudjin.

About 1194 Temudjin heard that one of the Taidshut chiefs, called Mutchin Sultu, had revolted against Madagu, the Kin Emperor of China, who had sent his chinsang (“prime minister”), Wan-jan-siang, with an army against him. He eagerly volunteered his services against the old enemies of his people, and was successful. He killed the chief and captured much booty; inter alia was a silver cradle with a covering of golden tissue, such as the Mongols had never before seen. As a reward for his services he received from the Chinese officer the title of jaut-ikuri — written “Tcha-u-tu-lu” in Hyacinthe, who says it means “commander against the rebels.” According to Raschid, on the same occasion Tului, the chief of the Keraits, was invested with the title of wang (“king”). On his return from this expedition, desiring to renew his intercourse with the Barins, he sent them a portion of the Tartar booty. The bearers of this present were maltreated. Mailla, who describes the event somewhat differently, says that ten of the messengers were killed by Sidsheh Bigi to revenge the indignities that had been put on his family. Temudjin now marched against the Barins, and defeated them at Thulan Buldak. Their two chiefs escaped. According to Mailla they were put to death.

In 1196 Temudjin received a visit from Wang Khan, the Kerait chief, who was then in distress. His brother Ilkah Sengun, better known as Jagampu Keraiti, had driven him from the throne. He first sought assistance from the chief of Kara Khitai, and, when that failed him, turned to Temudjin, the son of his old friend. Wang Khan was a chief of great consequence, and this appeal must have been flattering to him. He levied a contribution of cattle from his subjects to feast him with, and promised him the devotion of a son in consideration of his ancient friendship with Yissugei.

Temudjin was now, says Mailla, one of the most powerful princes of these parts, and he determined to subjugate the Kieliei, the inhabitants of the Argun, but he was defeated. During the action, having been hit by twelve arrows, he fell from his horse unconscious, when Bogordshi and Burgul, at some risk, took him out of the struggle. While the former melted the snow with some hot stones and bathed him with it, so as to free his throat from the blood, the latter, during the long winter night, covered him with his own cloak from the falling snow. He would, nevertheless, have fared badly if his mother had not collected a band of his father’s troops and come to his assistance together with Tului, the Kerait chief, who remembered the favors he had received from Temudjin’s father. Mailla says that returning home with a few followers, he was attacked by a band of robbers. He was accompanied by a famous crossbowman, named Soo, to whom he had given the name of Merghen. While the robbers were within earshot, Merghen shouted: “There are two wild ducks, a male and a female; which shall I bring down?”

“The male,” said Temudjin.

He had scarcely said so when down it came. This was too much for the robbers, who dared not measure themselves against such marksmanship.

The Merkits had recently made a raid upon his territory, and carried off his favorite wife, Burte Judjin. It was after her return from her captivity that she gave birth to her elder son, Juji, about whose legitimacy there seems to have been some doubt in his father’s mind. It was to revenge this that he now (1197) marched against them, and defeated them near the river Mundsheh (a river “Mandzin” is still to be found in the canton Karas Muren). He abandoned all the booty to Wang Khan. The latter, through the influence of Temudjin, once more regained his throne, and the following year (1198) he headed an expedition on his own account against the Merkits, and beat them at a place named Buker Gehesh, but he did not reciprocate the generosity of his ally.

In 1199 the two friends made a joint expedition against the Naimans. This tribe was now divided between two brothers who had quarrelled about their father’s concubine. One of them, named Buyuruk, had retired with a body of the people to the Kiziltash mountains. The other, called Baibuka — but generally referred to by his Chinese title of Taiwang, or Tayang — remained in his own proper country. It was the latter who was now attacked by the two allies, and forced to escape to the country of Kem Kemdjut — i.e., toward the sources of the Yenissei. Chamuka, the chief of the Jadjerats, well named Satchan, or “the Crafty,” still retained his hatred for Temudjin. He now whispered in the ear of Wang Khan that his ally was only a fair-weather friend. Like the wild goose, he flew away in winter, while he himself, like the snowbird, was constant under all circumstances. These and other suggestions aroused the jealousy of Wang Khan, who suddenly withdrew his forces, and left Temudjin in the enemy’s country. The latter was thereupon forced to retire also. He went to the river Sali or Sari. Gugsu Seirak, the Naiman general, went in pursuit, defeated Wang Khan in his own territory, and captured much booty. Wang Khan was hard pressed, and was perhaps only saved by the timely succor sent by Temudjin, which drove away the Naimans. Once more did the latter abandon the captured booty to his treacherous ally. After the victory, he held a Kuriltai, on the plains of Sari or Sali, to which Wang Khan was invited, and at which it was resolved to renew the war against the Taidshuts in the following year. The latter were in alliance with the Merkits, whose chief, Tukta, had sent a contingent, commanded by his brothers, to their help. The two friends attacked them on the banks of the river Onon. Raschid says in the country of Onon, i.e., the great desert of Mongolia. The confederates were beaten. Terkutai Kiriltuk and Kuduhar, the two leaders of the Taidshuts, were pursued and overtaken at Lengut Nuramen, where they were both killed. Another of their leaders, with the two chiefs of the Merkits, fled to Burghudshin, i.e., Burgusin on Lake Baikal, while the fourth found refuge with the Naimans.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.