This series has six easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: While His Parents Lived.

Introduction

Of all the barbarian tribes which invaded the realms of civilization, the Mongols stand out. Their time was centuries after the collapse of the Roman Empire, indeed even in the middle of Europe’s recovery from the Dark Age after the Roman end. Genghis Khan’s successors conquered China, the Middle East, Russia, and even India. This legacy made the Mongols even greater than any of the other barbarian tribes which erupted out of central Asia to attack the civilizations of the eastern hemisphere.

This selection is from History of the Mongols by Henry H. Howorth published in 1888. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Henry H. Howorth (1842-1923) was made Knight Commander of the Empire in recognition of his works on the history and ethnography of Asia.

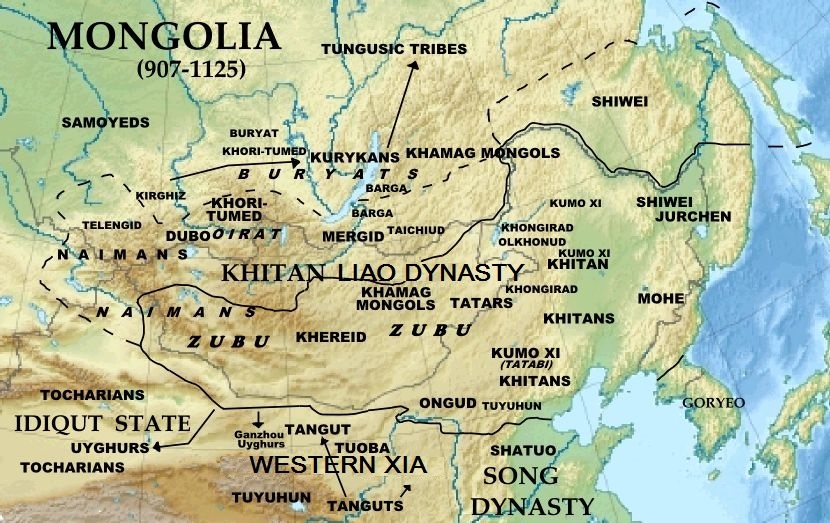

Time: 1162-1175

Place: Mongolia

CC BY-SA 4.0 image from Wikipedia

Among the men who have influenced the history of the world Genghis Khan holds a foremost place. Popularly he is mentioned with Attila and with Timur as one of the “scourges of God,” one of those terrible conquerors whose march across the page of history is figured by the simile of a swarm of locusts, or a fire in a Canadian forest; but this is doing gross injustice to Genghis Khan. Not only was he a conqueror, a general whose consummate ability made him overthrow every barrier that must intervene between the chief of a small barbarous tribe of an obscure race and the throne of Asia, and this with a rapidity and uniform success that can only be compared to the triumphant march of Alexander, but he was far more than a conqueror. Alexander, Napoleon, and Timur were all more or less his equals in the art of war. But the colossal powers they created were merely hills of sand, that crumbled to pieces as soon as they were dead.

With Genghis Khan matters were very different: he organized the empire which he had conquered so that it long survived and greatly thrived after he was gone. In every detail of social and political economy he was a creator; his laws and his administrative rules are equally admirable and astounding to the student. Justice, tolerance, discipline — virtues that make up the modern ideal of a state — were taught and practiced at his court. And when we remember that he was born and educated in the desert, and that he had neither the sages of Greece nor of Rome to instruct him, that unlike Charlemagne and Alfred he could not draw his lessons from a past whose evening glow was still visible in the horizon, we are tempted to treat as exaggerated the history of his times, and to be skeptical of so much political insight having been born of such unpromising materials.

It is not creditable to English literature that no satisfactory account of Genghis Khan exists in the language. Baron D’Ohsson in French, and Erdmann in German, have both written minute and detailed accounts of him, but none such exists in English, although the subject has an epic grandeur about it that might well tempt some well-grounded scholar to try his hand upon it.

Genghis Khan received the name of Temudjin. According to the vocabulary attached to the history of the Yuen dynasty, translated from the Chinese by Hyacinthe, temudjin means the best iron or steel. The name has been confounded with temurdji, which means a smith, in Turkish. This accounts for the tradition related by Pachymeres, Novairi, William of Ruysbrok, the Armenian Haiton, and others, that Genghis Khan was originally a smith.

The Chinese historians and Ssanang Setzen place his birth in 1162; Raschid and the Persians in 1155. The latter date is accommodated to the fact that they make him seventy-two years old at his death in 1227, but the historian of the Yuen dynasty, the Kangmu, and Ssanang Setzen are all agreed that he died at the age of sixty-six, and they are much more likely to be right. Mailla says he had a piece of clotted blood in his fist when born — no bad omen, if true, of his future career. According to De Guignes, Karachar Nevian was named his tutor.

Ssanang Setzen has a story that his father set out one day to find him a partner among the relatives of his wife, the Olchonods, and that on the way he was met by Dai Setzen, the chief of the Kunkurats, who thus addressed him: “Descendant of the Kiyots and of the race of the Bordshigs, whither hiest thou?”

“I am seeking a bride for my son,” was his reply. Dai Setzen then said that he recently had a dream, during which a white falcon had alighted on his hand. “This,” he said, “Bordshig, was your token. From ancient days our daughters have been wedded to the Bordshigs, and I now have a daughter named Burte who is nine years old. I will give her to thy son.”

“She is too young,” he said; but Temudjin, who was present, urged that she would suit him by and by. The bargain was thereupon closed, and, having taken a draught of koumiss and presented his host with two horses, Yissugei returned home.

On his father’s death Temudjin was only thirteen years old, an age that seldom carries authority in the desert, where the chief is expected to command, and his mother acted as regent. This enabled several of the tribes which had submitted to the strong hand of Yissugei to reassert their independence. The Taidshuts, under their leaders Terkutai, named Kiriltuk, i.e., the Spiteful, the great-grandson of Hemukai, and his nephew Kurul Bahadur, were the first to break away, and they were soon after joined by one of Yissugei’s generals with a considerable following. To the reproaches of Temudjin the latter answered: “The deepest wells are sometimes dry, and the hardest stones sometimes split; why should I cling to thee?” Temudjin’s mother, we are told, mounted her horse, and taking the royal standard called Tuk (this was mounted with the tails of the yak or mountain cow, or, in default, with that of a horse; it is the tau or tu of the Chinese, used as the imperial standard, and conferred as a token of royalty upon their vassals, the Tartar princes) in her hand, she led her people in pursuit of the fugitives, and brought a good number of them back to their allegiance.

After the dispersion of the Jelairs, many of them became the slaves and herdsmen of the Mongol royal family. They were encamped near Sarikihar, the Saligol of Hyacinthe, in the district of Ulagai Bulak, which D’Ohsson identifies with the Ulengai, a tri000000butary of the Ingoda, that rises in the watershed between that river and the Onon. One day Tagudshar, a relative of Chamuka, the chief of the Jadjerats, was hunting in this neighborhood, and tried to lift the cattle of a Jelair, named Jusi Termele, who thereupon shot him. This led to a long and bitter strife between Temudjin, who was the patron of the Jelairs, and Chamuka. He was of the same stock as Temudjin, and now joined the Taidshuts, with his tribe the Jadjerats. He also persuaded the Uduts and Nujakins, the Kurulas and Inkirasses, to join them.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.