This series has six easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Nailed to the Cross.

Introduction

The crucifixion story is a plausible historic event. After all, many others were crucified in antiquity. While Christians believe that Jesus’ specific suffering and dying was to make up for the sins of all humanity, one must note that history records many other worse tortures and more prolonged deaths than this one. So, by itself, the crucifixion of Jesus – even with the religious element of the redemption of all humanity’s sins tacked on – do not raise this story to the top-most rank of historical events.

What does not raise this story to the top-most rank of historical events is its connection to that other event three days later: the resurrection. The story of a man raising himself from the dead is unique to history, even though it may not be so in mythology. Unlike the crucifixion, the resurrection moves the story outside shared historical events to an unique supernatural plane.

If all of this is true, then these two events mark the central points in all world history. If not, they still form the core beliefs of one of the great religions of the world.

This selection is from Life of Christ by Frederic William Farrar published in 1874. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Frederic William Farrar (1831-1903) was a prominent Anglican cleric and author.

Time: c. 30 AD

Place: Golgatha, a Hill Ouside of Jersulam

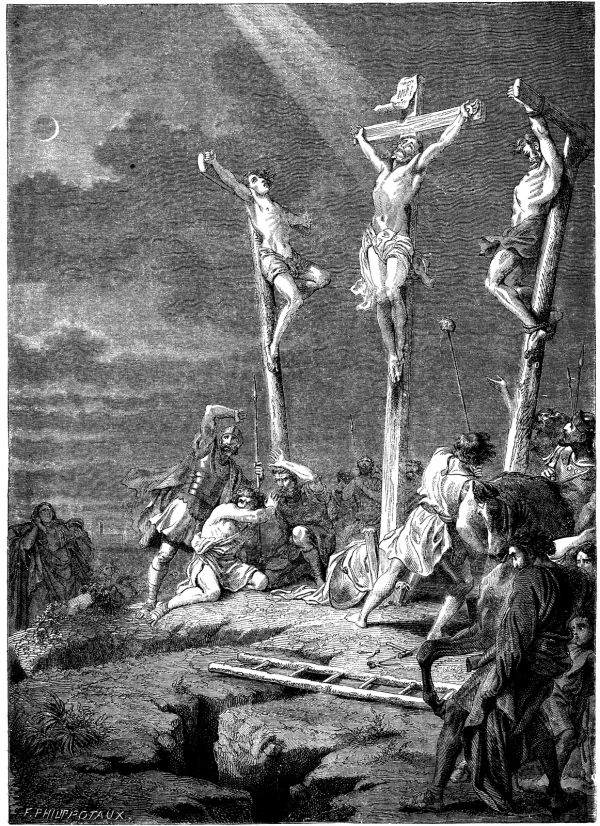

From clip art collection

Utterly brutal and revolting as was the punishment of crucifixion, which has now for fifteen hundred years been abolished by the common pity and abhorrence of mankind, there was one custom in Judea, and one occasionally practiced by the Romans, which reveal some touch of passing humanity. The latter consisted in giving to the sufferer a blow under the armpit, which, without causing death, yet hastened its approach. Of this I need not speak, because, for whatever reason, it was not practiced on this occasion. The former, which seems to have been due to the milder nature of Judaism, and which was derived from a happy piece of rabbinic exegesis on Prov. xxxi. 6, consisted in giving to the condemned, immediately before his execution, a draught of wine medicated with some powerful opiate. It had been the custom of wealthy ladies in Jerusalem to provide this stupefying potion at their own expense, and they did so quite irrespectively of their sympathy for any individual criminal. It was probably taken freely by the two malefactors, but when they offered it to Jesus he would not take it. The refusal was an act of sublimest heroism. The effect of the draught was to dull the nerves, to cloud the intellect, to provide an anaesthetic against some part at least of the lingering agonies of that dreadful death. But he, whom some modern sceptics have been base enough to accuse of feminine feebleness and cowardly despair, preferred rather “to look Death in the face” — to meet the king of terrors without striving to deaden the force of one agonizing anticipation, or to still the throbbing of one lacerated nerve.

The three crosses were laid on the ground — that of Jesus, which was doubtless taller than the other two, being placed in bitter scorn in the midst. Perhaps the cross-beam was now nailed to the upright, and certainly the title, which had either been borne by Jesus fastened round his neck or carried by one of the soldiers in front of him, was now nailed to the summit of his cross. Then he was stripped naked of all his clothes, and then followed the most awful moment of all. He was laid down upon the implement of torture. His arms were stretched along the cross-beams; and at the center of the open palms the point of a huge iron nail was placed, which, by the blow of a mallet, was driven home into the wood. Then through either foot separately, or possibly through both together as they were placed one over the other, another huge nail tore its way through the quivering flesh. Whether the sufferer was also bound to the cross we do not know; but, to prevent the hands and feet being torn away by the weight of the body, which could not “rest upon nothing but four great wounds,” there was, about the center of the cross, a wooden projection strong enough to support, at least in part, a human body which soon became a weight of agony.

It was probably at this moment of inconceivable horror that the voice of the Son of Man was heard uplifted, not in a scream of natural agony at that fearful torture, but calmly praying in divine compassion for his brutal and pitiless murderers — aye, and for all who in their sinful ignorance crucify him afresh forever: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

And then the accursed tree — with its living human burden hanging upon it in helpless agony, and suffering fresh tortures as every movement irritated the fresh rents in hands and feet — was slowly heaved up by strong arms, and the end of it fixed firmly in a hole dug deep in the ground for that purpose. The feet were but a little raised above the earth. The victim was in full reach of every hand that might choose to strike, in close proximity to every gesture of insult and hatred. He might hang for hours to be abused, outraged, even tortured by the ever-moving multitude who, with that desire to see what is horrible which always characterizes the coarsest hearts, had thronged to gaze upon a sight which should rather have made them weep tears of blood.

And there, in tortures which grew ever more insupportable, ever more maddening as time flowed on, the unhappy victims might linger in a living death so cruelly intolerable that often they were driven to entreat and implore the spectators or the executioners, for dear pity’s sake, to put an end to anguish too awful for man to bear — conscious to the last, and often, with tears of abject misery, beseeching from their enemies the priceless boon of death.

For indeed a death by crucifixion seems to include all that pain and death can have of horrible and ghastly — dizziness, cramp, thirst, starvation, sleeplessness, traumatic fever, tetanus, publicity of shame, long continuance of torment, horror of anticipation, mortification of untended wounds — all intensified just up to the point at which they can be endured at all, but all stopping just short of the point which would give to the sufferer the relief of unconsciousness. The unnatural position made every movement painful; the lacerated veins and crushed tendons throbbed with incessant anguish; the wounds, inflamed by exposure, gradually gangrened; the arteries — especially of the head and stomach — became swollen and oppressed with surcharged blood; and while each variety of misery went on gradually increasing, there was added to them the intolerable pang of a burning and raging thirst; and all these physical complications caused an internal excitement and anxiety which made the prospect of death itself — of death, the awful unknown enemy, at whose approach man usually shudders most — bear the aspect of a delicious and exquisite release.

Such was the death to which Christ was doomed; and though for him it was happily shortened by all that he had previously endured, yet he hung from soon after noon until nearly sunset before “he gave up his soul to death.”

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below. Special encouragement to read to this scholarly study.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.