Inscriptions on the oldest monuments prove that some of the earliest Pharaohs actually existed. But what of the rest?

Continuing The Dawn Of Civilization,

our selection from The Dawn of Civilization: Egypt and Chaldea by Gaston Maspero published in 1894. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in The Dawn Of Civilization.

Time: around 5900 BC

Place: Egypt

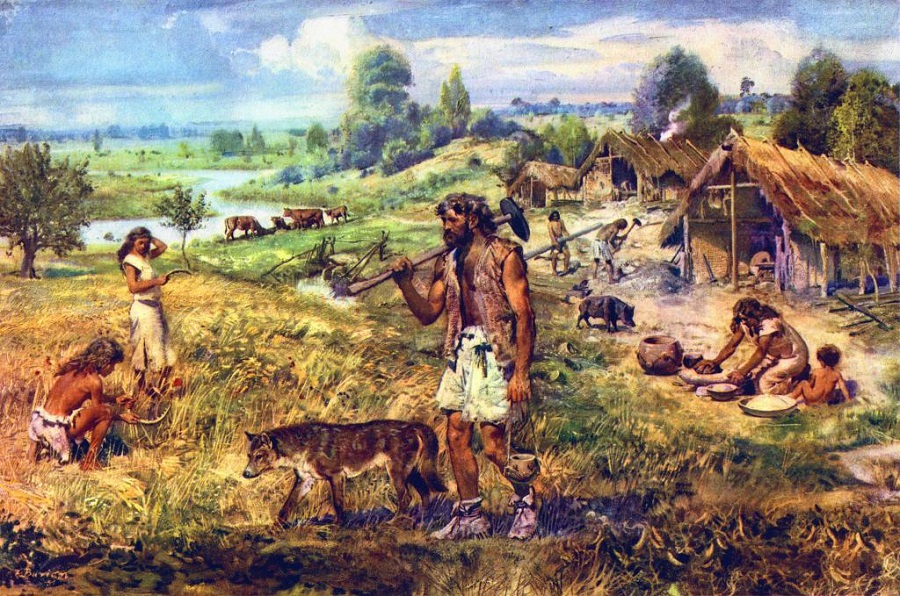

CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 image from Libcom.org

The inscriptions supply us with proofs that some of these princes lived and reigned: — Sondi, who is classed in the II dynasty, received a continuous worship toward the end of the III dynasty. But did all those who preceded him, and those who followed him, exist as he did? And if they existed, do the order and relation agree with actual truth? The different lists do not contain the same names in the same position; certain Pharaohs are added or suppressed without appreciable reason. Where Manetho inscribes Kenkenes and Ouenephes, the tables of the time of Seti I give us Ati and Ata; Manetho reckons nine kings to the II dynasty, while they register only five. The monuments, indeed, show us that Egypt in the past obeyed princes whom her annalists were unable to classify: for instance, they associated with Sondi a Pirsenu, who is not mentioned in the annals. We must, therefore, take the record of all this opening period of history for what it is — namely, a system invented at a much later date, by means of various artifices and combinations — to be partially accepted in default of a better, but without, according to it, that excessive confidence which it has hitherto received. The two Thinite dynasties, in direct descent from the fabulous Menes, furnish, like this hero himself, only a tissue of romantic tales and miraculous legends in the place of history. A double-headed stork, which had appeared in the first year of Teti, son of Menes, had foreshadowed to Egypt a long prosperity, but a famine under Ouenephes, and a terrible plague under Semempses, had depopulated the country; the laws had been relaxed, great crimes had been committed, and revolts had broken out.

During the reign of the Boethos a gulf had opened near Bubastis, and swallowed up many people, then the Nile had flowed with honey for fifteen days in the time of Nephercheres, and Sesochris was supposed to have been a giant in stature. A few details about royal edifices were mixed up with these prodigies. Teti had laid the foundation of the great palace of Memphis, Ouenephes had built the pyramids of Ko-kome near Saqqara. Several of the ancient Pharaohs had published books on theology, or had written treatises on anatomy and medicine; several had made laws called Kakôû, the male of males, or the bull of bulls. They explained his name by the statement that he had concerned himself about the sacred animals; he had proclaimed as gods, Hapis of Memphis, Mnevis of Heliopolis, and the goat of Mendes.

After him, Binothris had conferred the right of succession upon all women of the blood-royal. The accession of the III dynasty, a Memphite one according to Manetho, did not at first change the miraculous character of this history. The Libyans had revolted against Necherophes, and the two armies were encamped before each other, when one night the disk of the moon became immeasurably enlarged, to the great alarm of the rebels, who recognized in this phenomenon a sign of the anger of heaven, and yielded without fighting. Tosorthros, the successor of Necherophes, brought the hieroglyphs and the art of stone-cutting to perfection. He composed, as Teti did, books of medicine, a fact which caused him to be identified with the healing god Imhotpu. The priests related these things seriously, and the Greek writers took them down from their lips with the respect which they offered to everything emanating from the wise men of Egypt.

What they related of the human kings was not more detailed, as we see, than their accounts of the gods. Whether the legends dealt with deities or kings, all that we know took its origin, not in popular imagination, but in sacerdotal dogma: they were invented long after the times they dealt with, in the recesses of the temples, with an intention and a method of which we are enabled to detect flagrant instances on the monuments.

Toward the middle of the third century before our era the Greek troops stationed on the southern frontier, in the forts at the first cataract, developed a particular veneration for Isis of Philæ. Their devotion spread to the superior officers who came to inspect them, then to the whole population of the Thebaid, and finally reached the court of the Macedonian kings. The latter, carried away by force of example, gave every encouragement to a movement which attracted worshippers to a common sanctuary, and united in one cult two races over which they ruled. They pulled down the meagre building of the Saite period, which had hitherto sufficed for the worship of Isis, constructed at great cost the temple which still remains almost intact, and assigned to it considerable possessions in Nubia, which, in addition to gifts from private individuals, made the goddess the richest land-owner in Southern Egypt. Knumu and his two wives, Anukit and Satit, who, before Isis, had been the undisputed suzerains of the cataract, perceived with jealousy their neighbor’s prosperity: the civil wars and invasions of the centuries immediately preceding had ruined their temples, and their poverty contrasted painfully with the riches of the new-comer.

The priests resolved to lay this sad state of affairs before King Ptolemy, to represent to him the services which they had rendered and still continued to render to Egypt, and above all to remind him of the generosity of the ancient Pharaohs, whose example, owing to the poverty of the times, the recent Pharaohs had been unable to follow. Doubtless authentic documents were wanting in their archives to support their pretensions: they therefore inscribed upon a rock, in the island of Sehel, a long inscription which they attributed to Zosiri of the III dynasty. This sovereign had left behind him a vague reputation for greatness. As early as the XII dynasty Usirtasen III had claimed him as “his father” — his ancestor — and had erected a statue to him; the priests knew that, by invoking him, they had a chance of obtaining a hearing.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.