O Jesus, remember me when thou comest in thy kingdom.”

Continuing The Crucifixion of Jesus Christ,

our selection from Life of Christ by Frederic William Farrar published in 1874. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in The Crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

Time: c. 30 AD

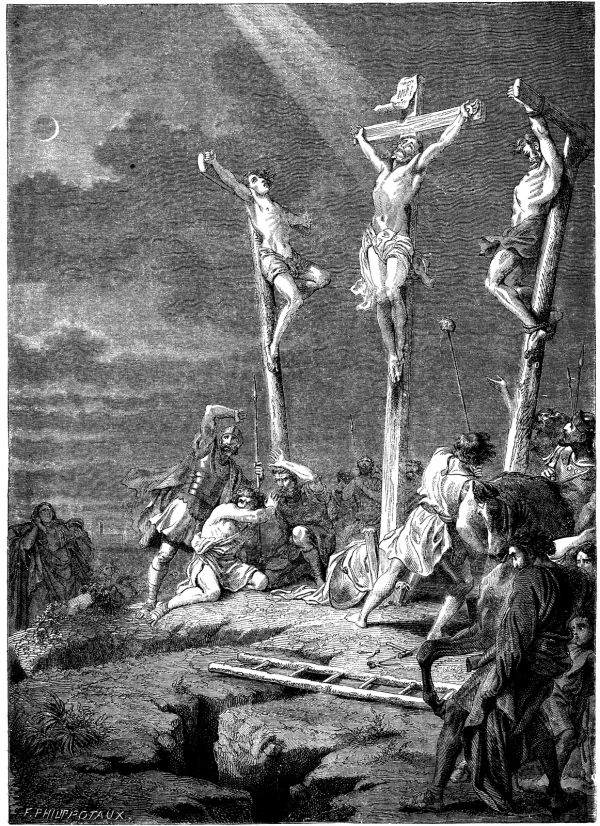

Place: Golgatha, a Hill Ouside of Jersulam

From clip art collection

But amid this chorus of infamy Jesus spoke not. He could have spoken. The pains of crucifixion did not confuse the intellect or paralyze the powers of speech. We read of crucified men who, for hours together upon the cross, vented their sorrow, their rage, or their despair in the manner that best accorded with their character; of some who raved and cursed, and spat at their enemies; of others who protested to the last against the iniquity of their sentence; of others who implored compassion with abject entreaties; of one even who, from the cross, as from a tribunal, harangued the multitude of his countrymen, and upbraided them with their wickedness and vice. But, except to bless and to encourage, and to add to the happiness and hope of others, Jesus spoke not. So far as the malice of the passers-by, and of priests and sanhedrists and soldiers, and of these poor robbers who suffered with him, was concerned — as before during the trial so now upon the cross — he maintained unbroken his kingly silence.

But that silence, joined to his patient majesty and the divine holiness and innocence which radiated from him like a halo, was more eloquent than any words. It told earliest on one of the crucified robbers. At first this bonus latro of the Apocryphal Gospels seems to have faintly joined in the reproaches uttered by his fellow-sinner; but when those reproaches merged into deeper blasphemy, he spoke out his inmost thought. It is probable that he had met Jesus before, and heard him, and perhaps been one of those thousands who had seen his miracles. There is indeed no authority for the legend which assigns to him the name of Dysmas, or for the beautiful story of his having saved the life of the Virgin and her Child during their flight into Egypt. But on the plains of Gennesareth, perhaps from some robber’s cave in the wild ravines of the Valley of the Doves, he may well have approached his presence — he may well have been one of those publicans and sinners who drew near to him for to hear him. And the words of Jesus had found some room in the good ground of his heart; they had not all fallen upon stony places. Even at this hour of shame and death, when he was suffering the just consequence of his past evil deeds, faith triumphed. As a flame sometimes leaps up among dying embers, so amid the white ashes of a sinful life which lay so thick upon his heart, the flame of love toward his God and his Savior was not quite quenched. Under the hellish outcries which had broken loose around the cross of Jesus there had lain a deep misgiving. Half of them seem to have been instigated by doubt and fear. Even in the self-congratulations of the priests we catch an undertone of dread. Suppose that even now some imposing miracle should be wrought! Suppose that even now that martyr-form should burst indeed into messianic splendor, and the King, who seemed to be in the slow misery of death, should suddenly with a great voice summon his legions of angels, and, springing from his cross upon the rolling clouds of heaven, come in flaming fire to take vengeance upon his enemies! And the air seemed to be full of signs. There was a gloom of gathering darkness in the sky, a thrill and tremor in the solid earth, a haunting presence as of ghostly visitants who chilled the heart and hovered in awful witness above that scene. The dying robber had joined at first in the half-taunting, half-despairing appeal to a defeat and weakness which contradicted all that he had hoped; but now this defeat seemed to be greater than victory, and this weakness more irresistible than strength. As he looked, the faith in his heart dawned more and more into the perfect day. He had long ceased to utter any reproachful words; he now rebuked his comrade’s blasphemies. Ought not the suffering innocence of him who hung between them to shame into silence their just punishment and flagrant guilt? And so, turning his head to Jesus, he uttered the intense appeal, “O Jesus, remember me when thou comest in thy kingdom.” Then he, who had been mute amid invectives, spake at once in surpassing answer to that humble prayer, “Verily, I say to thee, today shalt thou be with me in Paradise.”

Though none spoke to comfort Jesus — though deep grief, and terror, and amazement kept them dumb — yet there were hearts amid the crowd that beat in sympathy with the awful sufferer. At a distance stood a number of women looking on, and perhaps, even at that dread hour, expecting his immediate deliverance. Many of these were women who had ministered to him in Galilee, and had come from thence in the great band of Galilean pilgrims. Conspicuous among this heart-stricken group were his mother Mary, Mary of Magdala, Mary the wife of Clopas, mother of James and Joses, and Salome the wife of Zebedee. Some of them, as the hours advanced, stole nearer and nearer to the cross, and at length the filming eye of the Saviour fell on his own mother Mary, as, with the sword piercing through and through her heart, she stood with the disciple whom he loved. His mother does not seem to have been much with him during his ministry. It may be that the duties and cares of a humble home rendered it impossible. At any rate, the only occasions on which we hear of her are occasions when she is with his brethren, and is joined with them in endeavoring to influence, apart from his own purposes and authority, his messianic course. But although at the very beginning of his ministry he had gently shown her that the earthly and filial relation was now to be transcended by one far more lofty and divine, and though this end of all her high hopes must have tried her faith with an overwhelming and unspeakable sorrow, yet she was true to him in this supreme hour of his humiliation, and would have done for him all that a mother’s sympathy and love can do. Nor had he for a moment forgotten her who had bent over his infant slumbers, and with whom he had shared those thirty years in the cottage at Nazareth. Tenderly and sadly he thought of the future that awaited her during the remaining years of her life on earth, troubled as they must be by the tumults and persecutions of a struggling and nascent faith. After his resurrection her lot was wholly cast among his apostles, and the apostle whom he loved the most, the apostle who was nearest to him in heart and life, seemed the fittest to take care of her. To him, therefore — to John whom he had loved more than his brethren — to John whose head had leaned upon his breast at the Last Supper, he consigned her as a sacred charge. “Woman,” he said to her, in fewest words, but in words which breathed the uttermost spirit of tenderness, “behold thy son;” and then to St. John, “Behold thy mother.” He could make no gesture with those pierced hands, but he could bend his head. They listened in speechless emotion, but from that hour — perhaps from that very moment — leading her away from a spectacle which did but torture her soul with unavailing agony, that disciple took her to his own home.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below. Special encouragement to read to this scholarly study.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.