But now the end was very rapidly approaching, and Jesus, who had been hanging for nearly six hours upon the cross, was suffering from that torment of thirst which is most difficult of all for the human frame to bear.

Continuing The Crucifixion of Jesus Christ,

our selection from Life of Christ by Frederic William Farrar published in 1874. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in The Crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

Time: c. 30 AD

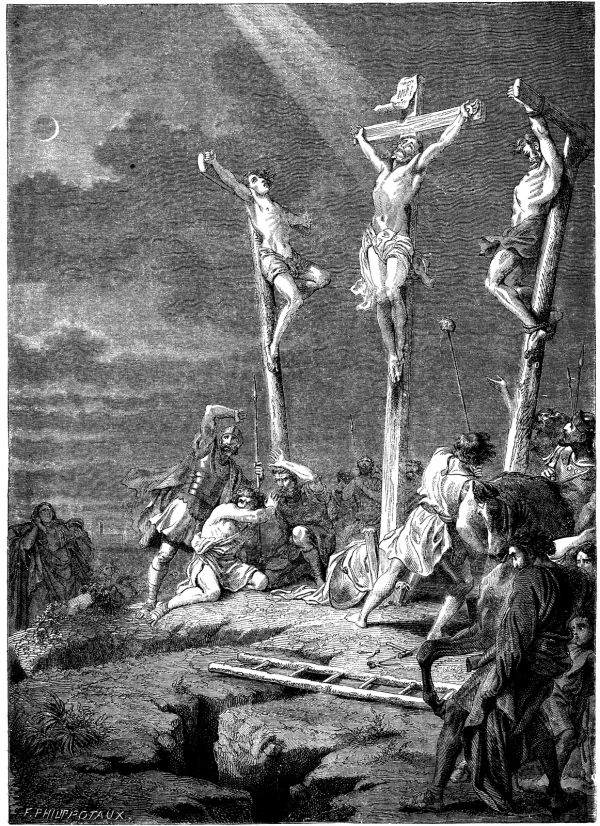

Place: Golgatha, a Hill Ouside of Jersulam

From clip art collection

It was now noon, and at the Holy City the sunshine should have been burning over that scene of horror with a power such as it has in the full depth of an English summer-time. But instead of this, the face of the heavens was black, and the noonday sun was “turned into darkness,” on “this great and terrible day of the Lord.” It could have been no darkness of any natural eclipse, for the Paschal moon was at the full; but it was one of those “signs from heaven” for which, during the ministry of Jesus, the Pharisees had so often clamored in vain. The early Fathers appealed to pagan authorities — the historian Phallus, the chronicler Phlegon — for such a darkness; but we have no means of testing the accuracy of these references, and it is quite possible that the darkness was a local gloom which hung densely over the guilty city and its immediate neighborhood. But whatever it was, it clearly filled the minds of all who beheld it with yet deeper misgiving. The taunts and jeers of the Jewish priests and the heathen soldiers were evidently confined to the earlier hours of the Crucifixion. Its later stages seem to have thrilled alike the guilty and the innocent with emotions of dread and horror. Of the incidents of those last three hours we are told nothing, and that awful obscuration of the noonday sun may well have overawed every heart into an inaction respecting which there was nothing to relate. What Jesus suffered then for us men and our salvation we cannot know, for during those three hours he hung upon his cross in silence and darkness; or, if he spoke, there was none there to record his words. But toward the close of that time his anguish culminated, and, emptied to the very uttermost of that glory which he had since the world began, drinking to the very deepest dregs the cup of humiliation and bitterness, enduring not only to have taken upon him the form of a servant, but also to suffer the last infamy which human hatred could impose on servile helplessness, he uttered that mysterious cry, of which the full significance will never be fathomed by man: Eli, Eli, lama Sabachthani? (“My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”)

In those words, quoting the psalm in which the early Fathers rightly saw a far-off prophecy of the whole passion of Christ, he borrowed from David’s utter agony the expression of his own. In that hour he was alone. Sinking from depth to depth of unfathomable suffering, until, at the close approach of a death which — because he was God, and yet had been made man — was more awful to him than it could ever be to any of the sons of men, it seemed as if even his divine humanity could endure no more.

Doubtless the voice of the sufferer — though uttered loudly in that paroxysm of an emotion which, in another, would almost have touched the verge of despair — was yet rendered more uncertain and indistinct from the condition of exhaustion in which he hung; and so, amid the darkness, and confused noise, and dull footsteps of the moving multitude, there were some who did not hear what he had said. They had caught only the first syllable, and said to one another that he had called on the name of Elijah. The readiness with which they seized this false impression is another proof of the wild state of excitement and terror — the involuntary dread of something great and unforeseen and terrible — to which they had been reduced from their former savage insolence. For Elijah, the great prophet of the Old Covenant, was inextricably mingled with all the Jewish expectations of a Messiah, and these expectations were full of wrath. The coming of Elijah would be the coming of a day of fire, in which the sun should be turned into blackness and the moon into blood, and the powers of heaven should be shaken. Already the noonday sun was shrouded in unnatural eclipse; might not some awful form at any moment rend the heavens and come down, touch the mountains and they should smoke? The vague anticipation of conscious guilt was unfulfilled. Not such as yet was to be the method of God’s workings. His messages to man for many ages more were not to be in the thunder and earthquake, not in rushing wind or roaring flame, but in the “still small voice” speaking always amid the apparent silences of Time in whispers intelligible to man’s heart, but in which there is neither speech nor language, though the voice is heard.

But now the end was very rapidly approaching, and Jesus, who had been hanging for nearly six hours upon the cross, was suffering from that torment of thirst which is most difficult of all for the human frame to bear — perhaps the most unmitigated of the many separate sources of anguish which were combined in this worst form of death. No doubt this burning thirst was aggravated by seeing the Roman soldiers drinking so near the cross; and happily for mankind, Jesus had never sanctioned the unnatural affectation of stoic impassibility. And so he uttered the one sole word of physical suffering which had been wrung from him by all the hours in which he had endured the extreme of all that man can inflict. He cried aloud, “I thirst.” Probably a few hours before, the cry would have only provoked a roar of frantic mockery; but now the lookers-on were reduced by awe to a readier humanity. Near the cross there lay on the ground the large earthen vessel containing the posca, which was the ordinary drink of the Roman soldiers. The mouth of it was filled with a piece of sponge, which served as a cork. Instantly someone — we know not whether he was friend or enemy, or merely one who was there out of idle curiosity — took out the sponge and dipped it in the posca to give it to Jesus.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below. Special encouragement to read to this scholarly study.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.