The history of Memphis, such as it can be gathered from the monuments, differs considerably from the tradition current in Egypt at the time of Herodotus.

Continuing The Dawn Of Civilization,

our selection from The Dawn of Civilization: Egypt and Chaldea by Gaston Maspero published in 1894. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in The Dawn Of Civilization.

Time: around 5900 BC

Place: Egypt

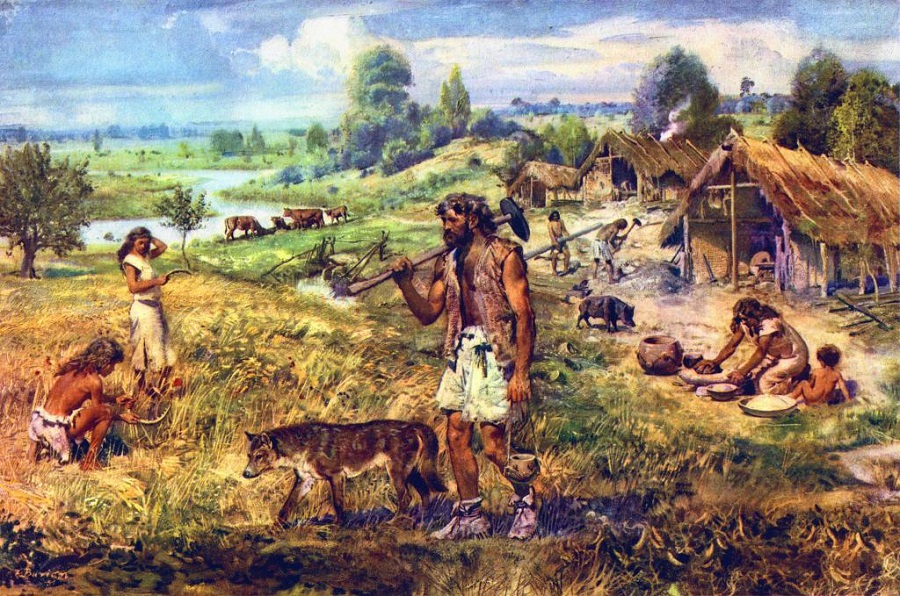

CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 image from Libcom.org

“This Menes, according to the priests, surrounded Memphis with dikes. For the river formerly followed the sand-hills for some distance on the Libyan side. Menes, having dammed up the reach about a hundred stadia to the south of Memphis, caused the old bed to dry up, and conveyed the river through an artificial channel dug midway between the two mountain ranges.

“Then Menes, the first who was king, having enclosed a space of ground with dikes, founded that town which is still called Memphis: he then made a lake around it to the north and west, fed by the river; the city he bounded on the east by the Nile.”

It appears, indeed, that at the outset the site on which it subsequently arose was occupied by a small fortress, Anbu-hazu — the white wall — which was dependent on Heliopolis and in which Phtah possessed a sanctuary. After the “white wall” was separated from the Heliopolitan principality to form a nome by itself it assumed a certain importance, and furnished, so it was said, the dynasties which succeeded the Thinite. Its prosperity dates only, however, from the time when the sovereigns of the V and VI dynasties fixed on it for their residence; one of them, Papi I, there founded for himself and for his “double” after him, a new town, which he called Minnofiru, from his tomb. Minnofiru, which is the correct pronunciation and the origin of Memphis, probably signified “the good refuge,” the haven of the good, the burying-place where the blessed dead came to rest beside Osiris.

The people soon forgot the true interpretation, or probably it did not fall in with their taste for romantic tales. They rather despised, as a rule, to discover in the beginnings of history individuals from whom the countries or cities with which they were familiar took their names: if no tradition supplied them with this, they did not experience any scruples in inventing one. The Egyptians of the time of the Ptolemies, who were guided in their philological speculations by the pronunciation in vogue around them, attributed the patronship of their city to a Princess Memphis, a daughter of its founder, the fabulous Uchoreus; those of preceding ages before the name had become altered thought to find in Minnofiru or “Mini Nofir,” or “Menes the Good,” the reputed founder of the capital of the Delta. Menes the Good, divested of his epithet, is none other than Menes, the first king of all Egypt, and he owes his existence to a popular attempt at etymology.

The legend which identifies the establishment of the kingdom with the construction of the city, must have originated at a time when Memphis was still the residence of the kings and the seat of government, at latest about the end of the Memphite period. It must have been an old tradition at the time of the Theban dynasties, since they admitted unhesitatingly the authenticity of the statements which ascribed to the northern city so marked a superiority over their own country. When the hero was once created and firmly established in his position, there was little difficulty in inventing a story about him which would portray him as a paragon and an ideal sovereign.

He was represented in turn as architect, warrior, and statesman; he had founded Memphis, he had begun the temple of Phtah, written laws and regulated the worship of the gods, particularly that of Hapis, and he had conducted expeditions against the Libyans. When he lost his only son in the flower of his age, the people improvised a hymn of mourning to console him — the “Maneros” — both the words and the tune of which were handed down from generation to generation.

He did not, moreover, disdain the luxuries of the table, for he invented the art of serving a dinner, and the mode of eating it in a reclining posture. One day, while hunting, his dogs, excited by something or other, fell upon him to devour him. He escaped with difficulty and, pursued by them, fled to the shore of Lake Moeris, and was there brought to bay; he was on the point of succumbing to them, when a crocodile took him on his back and carried him across to the other side. In gratitude he built a new town, which he called Crocodilopolis, and assigned to it for its god the crocodile which had saved him; he then erected close to it the famous labyrinth and a pyramid for his tomb.

Other traditions show him in a less favorable light. They accuse him of having, by horrible crimes, excited against him the anger of the gods, and allege that after a reign of sixty-two years he was killed by a hippopotamus which came forth from the Nile. They also relate that the Saite Tafnakhti, returning from an expedition against the Arabs, during which he had been obliged to renounce the pomp and luxuries of life, had solemnly cursed him, and had caused his imprecations to be inscribed upon a “stele” * set up in the temple of Amon at Thebes. Nevertheless, in the memory that Egypt preserved of its first Pharaoh, the good outweighed the evil. He was worshipped in Memphis, side by side with Phtah and Ramses II.; his name figured at the head of the royal lists, and his cult continued till the time of the Ptolemies.

[* The burned tile showing the impression of the stylus, made on the clay while plastic. — ED.]

His immediate successors have only a semblance of reality, such as he had. The lists give the order of succession, it is true, with the years of their reigns almost to a day, sometimes the length of their lives, but we may well ask whence the chroniclers procured so much precise information. They were in the same position as ourselves with regard to these ancient kings: they knew them by a tradition of a later age, by a fragment papyrus fortuitously preserved in a temple, by accidentally coming across some monument bearing their name, and were reduced, as it were, to put together the few facts which they possessed, or to supply such as were wanting by conjectures, often in a very improbable manner. It is quite possible that they were unable to gather from the memory of the past the names of those individuals of which they made up the first two dynasties. The forms of these names are curt and rugged, and indicative of a rude and savage state, harmonizing with the semi-barbaric period to which they are relegated: Ati the Wrestler, Teti the Runner, Qeunqoni the Crusher, are suitable rulers for a people the first duty of whose chief was to lead his followers into battle, and to strike harder than any other man in the thickest of the fight.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.