Today’s installment concludes The Dawn Of Civilization,

our selection from The Dawn of Civilization: Egypt and Chaldea by Gaston Maspero published in 1894. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in The Dawn Of Civilization.

Time: around 5900 BC

Place: Egypt

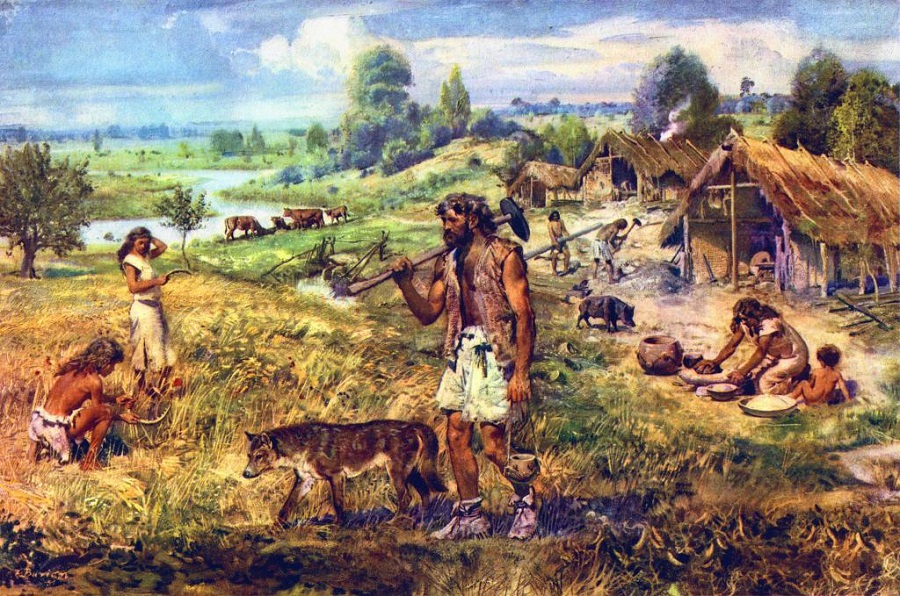

CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 image from Libcom.org

The inscription which they fabricated set forth that in the eighteenth year of Zosiri’s reign he had sent to Madir, lord of Elephantine, a message couched in these terms: “I am overcome with sorrow for the throne, and for those who reside in the palace, and my heart is afflicted and suffers greatly because the Nile has not risen in my time, for the space of eight years. Corn is scarce, there is a lack of herbage, and nothing is left to eat: when any one calls upon his neighbors for help, they take pains not to go. The child weeps, the young man is uneasy, the hearts of the old men are in despair, their limbs are bent, they crouch on the earth, they fold their hands; the courtiers have no further resources; the shops formerly furnished with rich wares are now filled only with air, all that was within them has disappeared. My spirit also, mindful of the beginning of things, seeks to call upon the savior who was here where I am, during the centuries of the gods, upon Thot-Ibis, that great wise one, upon Imhotpu, son of Phtah of Memphis. Where is the place in which the Nile is born? Who is the god or goddess concealed there? What is his likeness?”

The lord of Elephantine brought his reply in person. He described to the king, who was evidently ignorant of it, the situation of the island and the rocks of the cataract, the phenomena of the inundation, the gods who presided over it, and who alone could relieve Egypt from her disastrous plight.

Zosiri repaired to the temple of the principality and offered the prescribed sacrifices; the god arose, opened his eyes, panted, and cried aloud, “I am Khnumu who created thee!” and promised him a speedy return of a high Nile and the cessation of the famine.

Pharaoh was touched by the benevolence which his divine father had shown him; he forthwith made a decree by which he ceded to the temple all his rights of suzerainty over the neighboring nomes within a radius of twenty miles.

Henceforward the entire population, tillers and vinedressers, fishermen and hunters, had to yield the tithe of their income to the priests; the quarries could not be worked without the consent of Khnumu, and the payment of a suitable indemnity into his coffers; finally, metals and precious woods, shipped thence for Egypt, had to submit to a toll on behalf of the temple.

Did the Ptolemies admit the claims which the local priests attempted to deduce from this romantic tale? and did the god regain possession of the domains and dues which they declared had been his right? The stele shows us with what ease the scribes could forge official documents when the exigencies of daily life forced the necessity upon them; it teaches us at the same time how that fabulous chronicle was elaborated, whose remains have been preserved for us by classical writers. Every prodigy, every fact related by Manetho, was taken from some document analogous to the supposed inscription of Zosiri.

The real history of the early centuries, therefore, eludes our researches, and no contemporary record traces for us those vicissitudes which Egypt passed through before being consolidated into a single kingdom, under the rule of one man. Many names, apparently of powerful and illustrious princes, had survived in the memory of the people; these were collected, classified, and grouped in a regular manner into dynasties, but the people were ignorant of any exact facts connected with the names, and the historians, on their own account, were reduced to collect apocryphal traditions for their sacred archives.

The monuments of these remote ages, however, cannot have entirely disappeared: they existed in places where we have not as yet thought of applying the pick, and chance excavations will some day most certainly bring them to light. The few which we do possess barely go back beyond the III dynasty: namely, the hypogeum of Shiri, priest of Sondi and Pirsenu; possibly the tomb of Khuithotpu at Saqqara; the Great Sphinx of Gizeh; a short inscription on the rocks of Wady Maghara, which represents Zosiri (the same king of whom the priests of Khnumu in the Greek period made a precedent) working the turquoise or copper mines of Sinai; and finally the step pyramid where this Pharaoh rests. It forms a rectangular mass, incorrectly oriented, with a variation from the true north of 4° 35′, 393 ft., 8 in. long from east to west, and 352 ft. deep, with a height of 159 ft. 9 in. It is composed of six cubes, with sloping sides, each being about 13 ft. less in width than the one below it; that nearest to the ground measures 37 ft. 8 in. in height, and the uppermost one 29 ft. 2 in.

It was entirely constructed of limestone from neighboring mountains. The blocks are small and badly cut, the stone courses being concave, to offer a better resistance to downward thrust and to shocks of earthquake. When breaches in the masonry are examined, it can be seen that the external surface of the steps has, as it were, a double stone facing, each facing being carefully dressed. The body of the pyramid is solid, the chambers being cut in the rock beneath. These chambers have often been enlarged, restored, and reworked in the course of centuries, and the passages which connect them form a perfect labyrinth into which it is dangerous to venture without a guide. The columned porch, the galleries and halls, all lead to a sort of enormous shaft, at the bottom of which the architect had contrived a hiding-place, destined, no doubt, to contain the more precious objects of the funerary furniture. Until the beginning of this century the vault had preserved its original lining of glazed pottery. Three quarters of the wall surface was covered with green tiles, oblong and lightly convex on the outer side, but flat on the inner: a square projection pierced with a hole served to fix them at the back in a horizontal line by means of flexible wooden rods. Three bands which frame one of the doors are inscribed with the titles of the Pharaoh. The hieroglyphs are raised in either blue, red, green, or yellow, on a fawn-colored ground.

The towns, palaces, temples, all the buildings which princes and kings had constructed to be witnesses of their power or piety to future generations, have disappeared in the course of ages, under the feet and before the triumphal blasts of many invading hosts: the pyramid alone has survived, and the most ancient of the historic monuments of Egypt is a tomb.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The Dawn Of Civilization by Gaston Maspero from his book The Dawn of Civilization: Egypt and Chaldea published in 1894. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Dawn Of Civilization here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.